Article Type: Abstracts

Paul O’Connor 1, 2, Carla Sa-Couto 3, Sharon Marie Weldon 4, 6, Robyn Jane Stiger 7, 8, Colette Laws-Chapman 9

[1]

[2]

[3]

[4]

[5]

[6]

[7]

[8]

[9]

The Association for Simulated Practice in Healthcare (ASPiH) annual conference is held in Bournemouth, England from the 11th to the 13th November 2025. The three-day conference includes more than 170 poster presentations, 75 oral presentations, and 42 workshops. As can be seen from the published abstracts, a wide range of topics are addressed concerned with simulation education, technical innovation, and the use of simulation for transformation. Presenters and attendees come from a wide range of healthcare professions and specialties from across the UK, Ireland, and internationally, with participation from more than 15 countries spanning all 5 continents. This global participation underscores the theme of the conference: Simulation for Impact. More specifically, the impact of simulation on culture, co-production, and creativity.

Culture has been described as a slippery and ubiquitous concept [1]. This statement reflects the fact that there is no one agreed definition of culture, and the meaning has shifted over time. An anthropological definition of culture is “the socially transmitted knowledge and behaviour shared by some group of people” (p.23) [2]. The behavioural component of culture means that it is something that can be influenced through healthcare simulation. There are many examples of the use of simulation to impact the organisational culture. It has been suggested that in-situ simulation is particularly suited to providing valuable insight into both how ‘work is done’ and the related cultural aspects of the work in a healthcare unit [3]. There are also examples of the use of simulation to address specific aspects of organisational culture: such as safety culture or patient safety culture. For example, a Danish study found an improvement in healthcare providers’ perceptions of patient safety culture of healthcare providers following an in-situ simulation intervention [4].

An approach to using simulation to impact culture relates to improving the cultural competency of healthcare providers. Cultural competency is concerned with addressing barriers to the accessibility and effectiveness of health care services for people from racial or ethnic minorities [5]. In more recent years this concept has also been expanded to include language, sexual orientation, gender identity, class and professional status [6,7]. A systematic review of 27 papers concerned with providing simulated participant cultural competency education to student healthcare providers found that the intervention improved the cultural competence and confidence of learners [8]. More recently there has been a move away from cultural competence to cultural humility [9]. This is due to a recognition that culture perceived from a competency perspective implies that there is an endpoint to understanding culture when in reality it is fluid and requires an open and self-aware position [9,10]. Using simulation to improve cultural humility has great potential to promote equitable treatment of different cultural groups, and support culture differences across the healthcare system [9].

Co-production is an approach used to meaningfully integrate the knowledge, expertise, and experience of healthcare users into the design and delivery of healthcare services and research [11]. A distinct feature of co-production is that it does not distinguish between healthcare providers and recipients. This is achieved by reducing the social distance, knowledge, and power imbalances between different participant groups in the co-production activity [12]. It has been suggested that although co-production has great promise, it may be limited due to the risk of entanglement in existing involvement frameworks and practices [13]. Simulation offers an approach to address this limitation by providing a forum to support co-production. To illustrate, a systematic review of co-production in nursing and midwifery education identified 23 studies. It was concluded that there was preliminary evidence that participatory approaches can improve learning and positively impact on nursing and midwifery students, service users, and carers [14]. Additionally, simulation has been used to co-produce new models of care, generate more integrated care, and bridge gaps in understanding [15,16,17]. However, co-production within simulation remains limited with no clear definition of co-production within the context of healthcare simulation [18].

Creativity is integral to simulation. The range of simulation applications covered in the abstracts, posters, and workshops at ASPiH 2025 is a clear demonstration of the creativity of the community. Simulation has been described as ‘theatre with purpose’ [19]. This theatre analogy is very apt and recognises the creativity and imagination required to design and deliver simulation activities. However, this is only one aspect of simulation creativity. Increasingly simulation is also being used to impact health and care through collective understanding, insight, and learning garnered from transformative simulation approaches [20]. A visit to the ASPiH conference exhibition hall demonstrates the creativity of the simulation industry and the resulting sophistication and realism of the latest simulator technologies. It is therefore important to recognise that simulation is as complex as healthcare and more, and therefore designing it requires collective creativity to ensure it is intentional and impactful.

Although the use of simulation in healthcare might seem a relatively recent phenomenon, simulators have, in fact, been used to support the education of healthcare professionals for thousands of years. It has been suggested that the 20th century was a ‘dark age’ for healthcare simulation as compared to the previous two centuries [21]. Yet, the range of presentations, workshops, and industry stands at the APSiH 2025 conference suggest that we are now in a new and exciting age of healthcare simulation. One where the convergence of different cultures, co-production, and creativity is possible if we align with purpose.

Thank you to everyone who responded to the call for abstracts for this year’s ASPiH conference and to the scientific committee members involved in the reviewing process.

Authors’ contributions. POC conceived and wrote the first draft of the article. All other authors reviewed and contributed to subsequent drafts of the article and approved the final version.

Funding. None declared.

Availability of data and materials. Not applicable

Ethics approval and consent to participate. Not applicable

Competing interests. None declared.

1. Birukou A, Blanzieri E, Giorgini P, Giunchiglia F. A formal definition of culture. In: Sycara K, Gelfand M, Abbe A (Eds). Models for Intercultural Collaboration and Negotiation. Advances in Group Decision and Negotiation, Vol 6. London: Springer. 2013. pp. 1–26.

2. Peoples JG, Garrick AB. Humanity: An Introduction to Cultural Anthropology. Belmont, CA: West/Wadsworth. 1994.

3. Patterson MD, Eisenberg EM, Murphy A. Using Simulation to Understand and Shape Organizational Culture. In: Deutsch ES, Perry SJ, Gurnaney HG (Eds.). Comprehensive Healthcare Simulation: Improving Healthcare Systems. London: Springer. 2021. pp. 169–17.

4. Schram A, Paltved C, Christensen KB, Kjaergaard-Andersen G, Jensen HI, Kristensen S. Patient safety culture improves during an in situ simulation intervention: a repeated cross-sectional intervention study at two hospital sites. BMJ Open Quality. 2021;10(1):e001183.

5. Truong M, Paradies Y, Priest N. Interventions to improve cultural competency in healthcare: a systematic review of reviews. BMC health services research. 2014;14(1):99.

6. Yu H, Flores DD, Bonett S, Bauermeister JA. LGBTQ+ cultural competency training for health professionals: a systematic review. BMC medical education. 2023;23(1):55.

7. World Health Organisation. Cultural contexts of health and well-being principal author and editor culture matters: using a cultural context of health approach to enhance policymaking. 2020. Available from: https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0009/334269/14780_World-Health-Organisation_Context-of-Health_TEXT-AW-WEB.pdf.

8. Walkowska A, Przymuszała P, Marciniak-Stępak P, Nowosadko M, Baum E. Enhancing cross-cultural competence of medical and healthcare students with the use of simulated patients- a systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023;20(3):2505.

9. Gonzales-Walters F, Weldon S, Essex R. Cultivating cultural humility through healthcare simulation-based education: a scoping review protocol. International Journal of Healthcare Simulation. 2024; doi: 10.54531/rafh4191.

10. Foronda C, Baptiste DL, Reinholdt MM, Ousman K. Cultural humility: a concept analysis. Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 2016;27(3):210–217.

11. Filipe A, Renedo A, Marston C. The co-production of what? Knowledge, values, and social relations in health care. 2017; PLoS Biology. 15(5): e2001403.

12. Ramrez R. Value co-production: intellectual origins and implications for practice and research. Strategic Management Journal.1999;20:4965.

13. Bovaird T. Beyond engagement and anticipation: user and community co-production of public services. Public Administration Review. 2007;67: 846860.

14. O’Connor S, Zhang M, Trout KK, Snibsoer AK. Co-production in nursing and midwifery education: A systematic review of the literature. Nurse Education Today. 2021;102:104900

15. Weldon SM, Kneebone R, Bello F. Collaborative healthcare remodelling through sequential simulation: a patient and front-line staff perspective. BMJ Simululation and Technology Enhanced Learning. 2016. 27;2(3):78–86.

16. Weldon S-M, Ralhan S, Paice E, Kneebone R, Bello F. Sequential simulation of a patient pathway. Clinical Teacher. 2016;14(2):90–94.

17. Kneebone R, Weldon S-M, Bello F. Engaging patients and clinicians through simulation: rebalancing the dynamics of care. Advances in Simulation 2016;1:19. doi: 10.1186/s41077-016-0019-9.

18. Philpott L, Markowski M & Weldon SM. Lived experience co-production in simulation education and practice- a scoping review protocol. Journal of Healthcare Simulation. 2025. [In print].

19. Dieckmann P, Gaba D, Rall M. Deepening the theoretical foundations of patient simulation as social practice. Simulation in Healthcare. 2007; 2(3):183–93.

20. Weldon SM, Buttery AG, Spearpoint K, Kneebone R. Transformative forms of simulation in health care-the seven simulation-based ‘I’s: a concept taxonomy review of the literature. International Journal of Healthcare Simulation. 2023 Jul 7:1–13.

21. Owen H. Early Use of Simulation in Medical Education. Simulation in Healthcare. 2012;7(2):102–116.

Diana Dupont 1, Karen Furlong 1, Jaime Riley 2

[1]

[2]

A multi-patient simulation involving patients with acute health challenges was co-created by nursing faculty at the University of New Brunswick, Canada. The integration of this simulation occurred during the 2023 Fall term. Presented findings are focussed on data collected in the 2024 Fall term as research leads obtained ethical approval prior to this second offering. Although simulation-based experiences (SBEs) are well established as effective tools in building capacity in health care programs [1], the use of multi-patient simulations in support of skills such as clinical judgement and time management remain underexplored. The National Council State Boards of Nursing’s Clinical Judgement Measurement Model (CJMM)[2] helped frame learning objectives while INASCL standards were adhered to in the design of this simulation [3]. The purpose of this presentation is to share key findings and recommendations for a study exploring student perceptions of this multi-patient SBE.

A mixed-methods approach was used in this study. Quantitative data were collected using pre- (n=70) and post-(n=60) simulation quizzes, with questions aligned to learning objectives. These quizzes assessed students’ knowledge and clinical judgement before and after the simulation. Qualitative data were collected through two focus groups (n=7) which included an exploration of students’ perceptions of elements impacting their ability to meet learning objectives. Quantitative data were analysed using descriptive statistics. Content analysis was used to identify key concepts which were organized into categories.

Quiz responses between subgroups of students were compared – students were either enrolled in the BN program through a bridging model or entered through a four-year pathway. All students scored poorly on questions involving teamwork and scope of practice considerations. In contrast, students who entered the BN program through the bridging model scored significantly higher on time management.

Content analysis of focus group data revealed key categories: 1) knowing what to expect and what is expected of me; 2) realism as a performance factor; and; 3) acknowledging the impact of past experience.

Findings from this study offer insights into how senior nursing students experience and respond to a multi-patient simulation. Relationships between previous clinical experience, preparation, perceived realism, and the link to performance have implications for simulation design and teaching and learning strategies beyond a simulation context. A limitation of this study is the focus group participants included only students enrolled in the four-year pathway.

As the submitting author, I can confirm that all relevant ethical standards of research and dissemination have been met. Additionally, I can confirm that the necessary ethical approval has been obtained, where applicable.

1. Bray L, Østergaard D. A qualitative study of the value of simulation-based training for nursing students in primary care. BMC Nursing. 2024;23(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12912-024-01886-0.

2. National Council of State Boards of Nursing. (2019). Clinical judgment measurement model. Next Generation NCLEX News,13, 1–6. Available from: https://www.ncsbn.org/public-files/NGN_Winter19.pdf

3. INACSL Standards Committee, Watts PI, McDermott DS, Alinier G, Charnetski M, Ludlow J, Horsley E, Meakim C, Nawathe P. Healthcare Simulation Standards of Best Practice® Simulation Design. Clinical Simulation in Nursing, 2021;58:14–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ecns.2021.08.009.

Ingrid Bispo 1, Carla Cerqueira 2, Isilda Ribeiro 2, Cristina Carvalho 2, Fernanda Carvalho 2, Carla Sá-Couto 1

[1]

[2]

Simulation-based interprofessional (IP) education programs at the undergraduate level remain limited both worldwide [1] and within the Portuguese educational context [2]. The LINKS workshop - Lifting INterprofessional Knowledge through Simulation - is a novel initiative designed for IP teams of healthcare students (medicine and nursing). It aims to enhance team-based behavioural competencies that are essential for effective IP teamwork. This pilot study aims to assess the impact of the LINKS workshop on communication skills within IP undergraduate teams.

This quasi-experimental study involved final-year medical and nursing students participating in a 4-hour, simulation-based IP workshop. Working in mixed teams, students managed two clinical scenarios designed to promote interprofessional communication, each offering equivalent challenges and opportunities to practice key communication strategies. Each scenario was followed by a structured debriefing led by experienced facilitators, focusing on teamwork skills, including key communication strategies. A total of thirteen IP teams participated. The scenarios were video recorded for subsequent analysis of the teams’ performance.

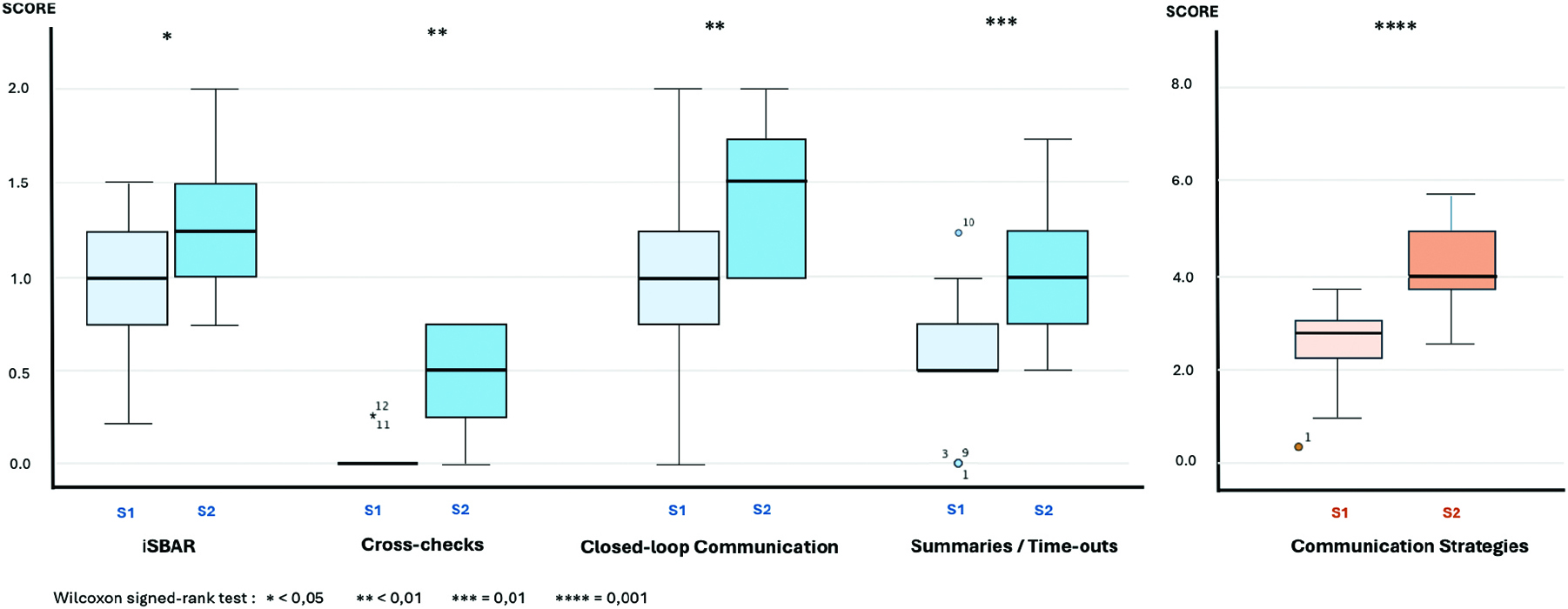

Interprofessional communication was assessed using an observational tool for monitoring non-technical skills [3], focusing on four communication strategies: (1) iSBAR (e.g., identification, situation, background, assessment and request/recommendation); (2) cross-checks; (3) closed-loop communication; and (4) summaries/time-outs. Four independent observers reviewed the recordings and scored team performance on each communication skill, using a 3-points scale: 0 - Not observed; 1 - Observed but inconsistent or incorrect use; 2 - Observed consistently and correctly used.

The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to compare performance in both scenarios. Inter-rater reliability was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha. This study was approved by the ethical committee of the Faculty of Medicine of the University of Porto, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Internal consistency of communication strategies scores was acceptable (Cronbach 0.7 ≤ α < 0.8), for both scenarios. Statistically significant improvements were observed in all four communication strategies and in the overall communication score between the two scenarios (p<0.05, Figure 1).

Teams demonstrated improved use of communication strategies in the second scenario, suggesting a positive effect of the IP simulation activity combined with a structured debriefing. This pilot study reinforces the value of simulation-based IP educational at the undergraduate level in clarifying professional roles and enhancing team communication. Continued implementation of such programs within clinical training can foster essential teamwork competencies and drive meaningful curriculum reform, preparing students for effective collaborative practice in healthcare settings.

As the submitting author, I can confirm that all relevant ethical standards of research and dissemination have been met. Additionally, I can confirm that the necessary ethical approval has been obtained, where applicable.

1. Choudhury RI, Salam Mau, Mathur J, et al. How interprofessional education could benefit the future of healthcare – medical students’ perspective. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20:242.

2. Sa-Couto C, Fernandes F, Pinto CC, Loureiro E, Cerqueira C. Impact of a simulation-based interprofessional workshop (LINKS) on Portuguese healthcare students’ perception of roles and competencies: a quasi-experimental pilot study. Int J Healthc Simul. 2024;XX(XX). doi: 10.54531/PRHF1746

3. Rosário L, Sá-Couto CD, Loureiro E. An observational and action-based tool for non-technical skills monitoring in Simulation-Based Training. SESAM 2019 Proceedings.

Box plots illustrating team scores (n=13) for each communication strategy in Scenario 1 (S1) and Scenario 2 (S2). Scores represent the mean ratings from the four independent observers, assessing the application and consistency of the communication strategies.

Oliver Hart 1, Alex Hall 2, Johann Willers 2

[1]

[2]

Emergency department thoracotomy (EDT) in children is a rare, high-stakes procedure performed primarily during traumatic cardiac arrest [1]. Training opportunities are limited, and current reliance on porcine models raises ethical concerns and lacks paediatric anatomical fidelity. This project aimed to develop and evaluate a low-cost, Aqueous Dietary fibre Antifreeze Mix gel (ADAMgel) based, synthetic model tailored to paediatric EDT, improving training accessibility, anatomical realism, and trainee confidence [2].

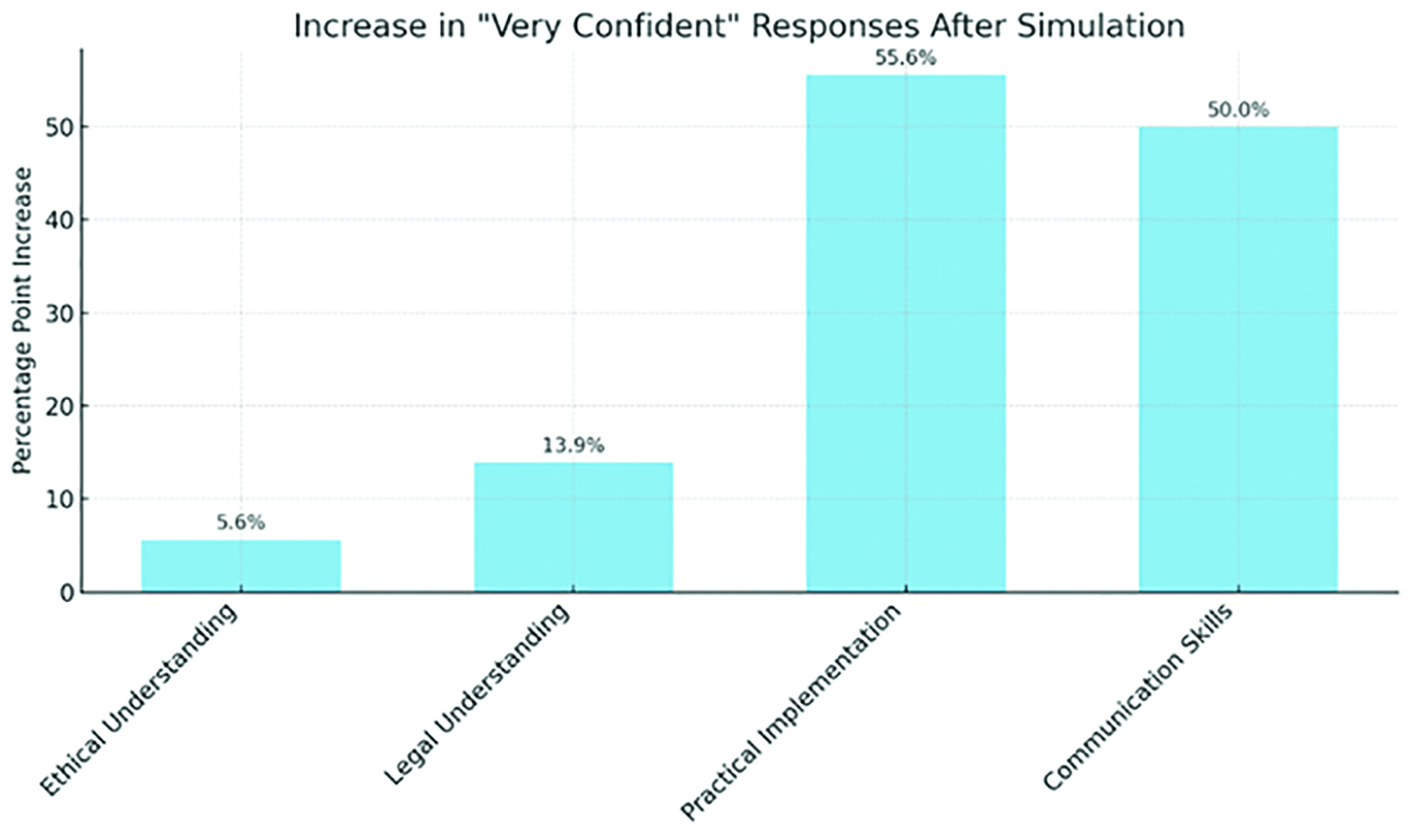

A novel thoracotomy model replicating the thoracic cavity of a 9-year-old child was constructed using synthetic materials, including ADAMgel-laminated soft tissues and a skeletal framework, Figure 1. The model underwent iterative development informed by expert focus groups. Final evaluation included two simulation sessions with doctors (n=11), who completed pre- and post-simulation Likert scale questionnaires assessing confidence and understanding. Data were collected between January and March 2025. Results were analysed using Wilcoxon signed-rank tests. Qualitative feedback was gathered from participants and faculty at the Royal College of Surgeons (RCS) Pre-hospital emergency resuscitative thoracotomy course.

All procedures were conducted with appropriate institutional approval for educational simulation-based research.

Statistically significant improvements were observed across several domains: confidence in performing EDT increased from median 1 to 4 (p=0.027), understanding of the procedure (p=0.016) and anatomy (p=0.019) also improved. All participants unanimously agreed the model improved their confidence and was a useful training aid. Surface tissues were rated realistic by 91%, and bony structures by 82%. Feedback from RCS faculty highlighted the model’s advantages over porcine equivalents, including reusability, independent practice opportunities, and superior anatomical accuracy. Suggested improvements included stronger tissue fixation and simulated aortic control.

This ADAMgel-based model demonstrates a feasible, ethical, and effective alternative to animal models in paediatric EDT simulation. Improvements in learner confidence and anatomical understanding support its utility in early procedural training. Planned enhancements, including aortic occlusion simulation, will increase fidelity. Broader validation across experience levels will determine its future role in standardised trauma education.

As the submitting author, I can confirm that all relevant ethical standards of research and dissemination have been met. Additionally, I can confirm that the necessary ethical approval has been obtained, where applicable.

1. Moskowitz EE, Burlew CC, Kulungowski AM, Bensard DD. Survival after emergency department thoracotomy in paediatric trauma. Pediatr Surg Int. 2018;34(8):857–860.

2. Clifford E, Stourton F, Willers J, Colucci G. Development of a Low-Cost, High-Fidelity, Reusable Model to Simulate Clamshell Thoracotomy. Surg Innov. 2023;30(6):739–744.

Anoopkishore Chidambaram 1

[1]

Simulation-based education (SBE) has become a cornerstone of healthcare training, providing hands-on learning experiences that develop technical proficiency while also promoting critical thinking and clinical judgement [1-3]. These cognitive skills are essential for delivering safe and effective patient care. This scoping review explores recent innovations in SBE and examines their impact on the development of critical thinking and decision-making among undergraduate and postgraduate healthcare learners.

A structured scoping review was conducted using peer-reviewed articles published between 2020 and 2025. A systematic search strategy, developed with support from an academic librarian, identified relevant studies across CINAHL, MEDLINE, and Embase databases. Inclusion criteria focused on studies reporting outcomes related to critical thinking or clinical decision-making within a simulation context. Both qualitative and quantitative studies were included. A thematic synthesis approach was applied to identify key patterns across different simulation modalities (e.g., high-fidelity simulation, virtual reality, blended learning) and learner groups.

Thirty-three articles met the inclusion criteria. The findings consistently demonstrate that SBE enhances learners’ critical thinking and clinical reasoning abilities. Effective educational strategies included the use of high-fidelity simulation environments, structured debriefing, psychological safety, and reflective learning models. Technological innovations, particularly screen-based simulation and virtual reality (VR), were noted to improve learner engagement and cognitive development. Interprofessional simulations were highlighted as valuable in supporting real-time decision-making under pressure. However, evidence regarding the long-term retention and clinical transferability of these skills was limited.

Simulation-based education appears highly effective in promoting critical thinking and clinical decision-making skills within healthcare education. Successful outcomes depend on deliberate instructional design, appropriate use of fidelity, effective feedback processes, and learner-centred approaches. While technological advances offer promising new avenues for skill development, further longitudinal research is needed to determine the durability of these cognitive gains and their impact on clinical practice. These insights may inform the future design and optimisation of simulation-based curricula.

As the submitting author, I can confirm that all relevant ethical standards of research and dissemination have been met. Additionally, I can confirm that the necessary ethical approval has been obtained, where applicable.

1. Alharbi A, Nurfianti A, Mullen RF, et al. Enhancing critical thinking through simulation: a systematic review. BMC Med Educ. 2024;24(1):1099–1111.

2. Stenseth HV, Steindal SA, Solberg MT, et al. Virtual reality in healthcare simulation: a systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2025;27:e58744.

3. Marchi AJ, Paganotti L. Simulation fidelity and clinical judgement: a narrative review. Simul Healthc. 2025;20(1):N.PAG.

Emma-May Curran 1, Victoria Meighan

[1]

Haemorrhagic shock is the one of the leading causes of death in trauma patients and early recognition of blood loss, haemorrhage control and rapid massive transfusion is lifesaving [1]. Efficient delivery of blood products is essential to the care of trauma patients [2] and is dependent on excellent multi-disciplinary teamwork and communication.

In our institution, a Dublin based designated Trauma Unit, we sought to investigate the effect of multi-disciplinary simulation based medical education on time to delivery of blood products in a massive transfusion.

Four multi-disciplinary team (MDT) simulation based medical education training sessions were held between 2020 and 2022. The MDT included prehospital National Ambulance Service, emergency department medical and nursing staff, porters, health care assistants, surgical and intensive care doctors and blood bank staff.

Each simulation was based on a major trauma and used a standardised massive transfusion protocol.

To evaluate the efficacy of the MDT simulation-based training, a retrospective review was carried out which analysed the; i) Activation of the massive transfusion protocol, ii) time to issue pack one, and, iii) time for pack one to be collected from the lab.

Prior to the MDT simulation-based education the average time from activation of the MTP to the blood arriving in the emergency department was in excess of 40 minutes. After conducting the training, the time decreased to 32 minutes. The average time from activation of the MTP to issuing pack one was 13 minutes and from issuing the blood to delivery to the emergency department was 20 minutes which was a significant improvement on the pre-training times.

We demonstrated a reduction in time to delivery of blood products associated with regular MDT in situ simulation training. Deliberate practice of the massive transfusion protocol improved teamwork and communication which lead to a reduction in time taken for the delivery of blood products.

As the submitting author, I can confirm that all relevant ethical standards of research and dissemination have been met. Additionally, I can confirm that the necessary ethical approval has been obtained, where applicable.

1. Eastridge BJ, Holcomb JB, Shackelford S. Outcomes of traumatic hemorrhagic shock and the epidemiology of preventable death from injury. Transfusion. 2019;59:1423–1428. doi: 10.1111/trf.15161.

2. Nunez TC, Young PP, Holcomb JB, Cotton BA. Creation, implementation, and maturation of a massive transfusion protocol for the exsanguinating trauma patient. J Trauma. 2010 Jun;68(6):1498–505. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181d3cc25. PMID: 20539192; PMCID: PMC3136378.

Helen Jarvis 1, Tiffany McCurdy 1, Rufaro Ndokera 1, Emma Sang 1

[1]

There is limited research providing guidance on deliverance of in-situ simulation (ISS) in ambulances, within the transport setting. Previous studies have shown that only 67% of UK neonatal transport teams provide ISS and this takes place less than weekly in 60% of teams surveyed [1]. Simulation-based education (SBE) is well established in enhancing team-work, communication and awareness of human factors, all of which are significantly more challenging in transport, due to clinical isolation, scarcity of resources and physical and sound barriers.

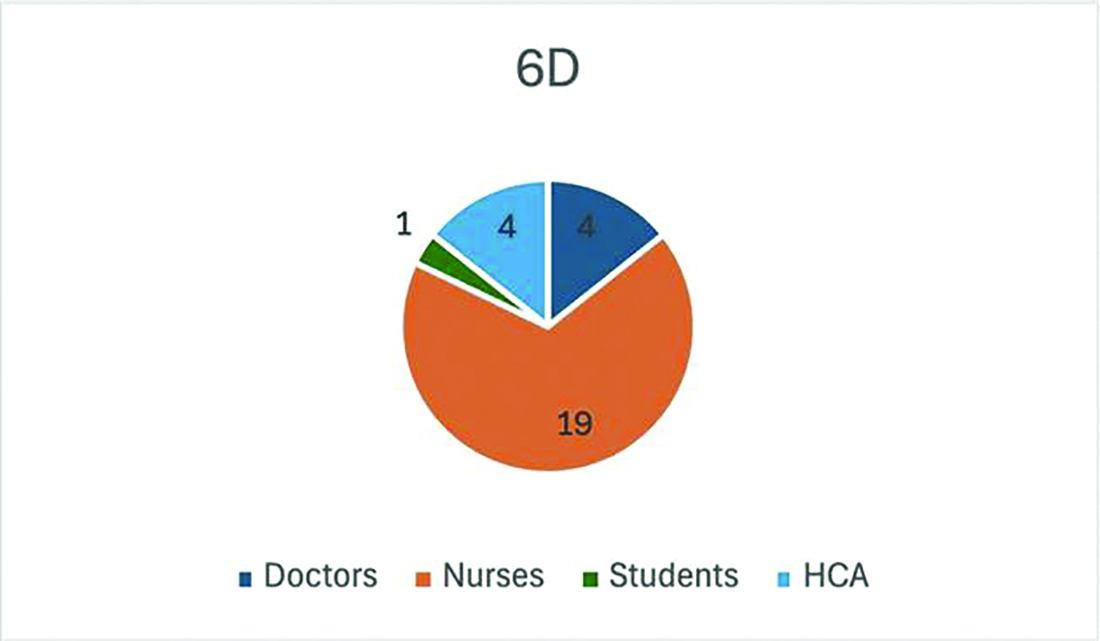

KIDSNTS is a joint paediatric and neonatal transport service, covering the West-Midlands region. Many staff members are dually trained in paediatric and neonatal retrieval allowing speciality collaboration. St Johns Ambulance technicians additionally contribute to the multi-disciplinary team (MDT) care. Many team members have limited or no experience of SBE previously. Joint ISS delivery literature is scarce.

This project will evaluate the newly introduced KIDSNTS ISS programme. MDT ISS’ run at least twice-monthly and cover neonatal and paediatric scenarios. A continued review of staff pre- and post-ISS questionnaires will examine SBE expectations and prior experience. Psychological measures of wellbeing, stress and self-efficacy will be tested with staff attending ISS, to determine their feasibility for measuring long-term service impact. Prospectively, objective data will be collected from stabilisation times and adverse event submissions to evaluate ISS impact. Data will be used to provide future direction for the KIDSNTS programme.

In less than a year since introduction, the KIDSNTS simulation team, comprising of a neonatal and a paediatric consultant, and a dually-trained education lead nurse, has so far delivered close to 20 ISS, reaching approximately 50 staff members. Pre-ISS feedback has revealed ongoing staff anxiety and reluctance to engage in SBE. Early post-ISS feedback however, indicate that staff have all experienced positive learning outcomes and are eager to continue to take part. Introduction of a pre-briefing information video, general raised awareness of SBE, as well as pre-planned, clinically monthly-themed scenarios are all being undertaken, aiming to lessen anxiety and increase uptake. ISS has already led to service provision changes and increased enthusiasm for SBE, with some team members undertaking additional training to be become simulation facilitators.

Evaluating KIDSNTS staff perceived barriers to transport ISS will support the embedding and success of the SBE programme. Further research will focus on the positive outcomes that ISS will have on safe patient transport care, as well as staff confidence and well-being.

As the submitting author, I can confirm that all relevant ethical standards of research and dissemination have been met. Additionally, I can confirm that the necessary ethical approval has been obtained, where applicable.

1. MacLaren AT, Peters C. In situ simulation in neonatal transport. Infant. 2016;12(5):168–170.

Sasha Bryan 1, Amy Purse 1, Chelsea Curry 1, Heidi Singleton 1, Bernice Law 1, Jakob Rossner 1, Emily Brooks 1, Alex Hull 1, Debbie Holley 1

[1]

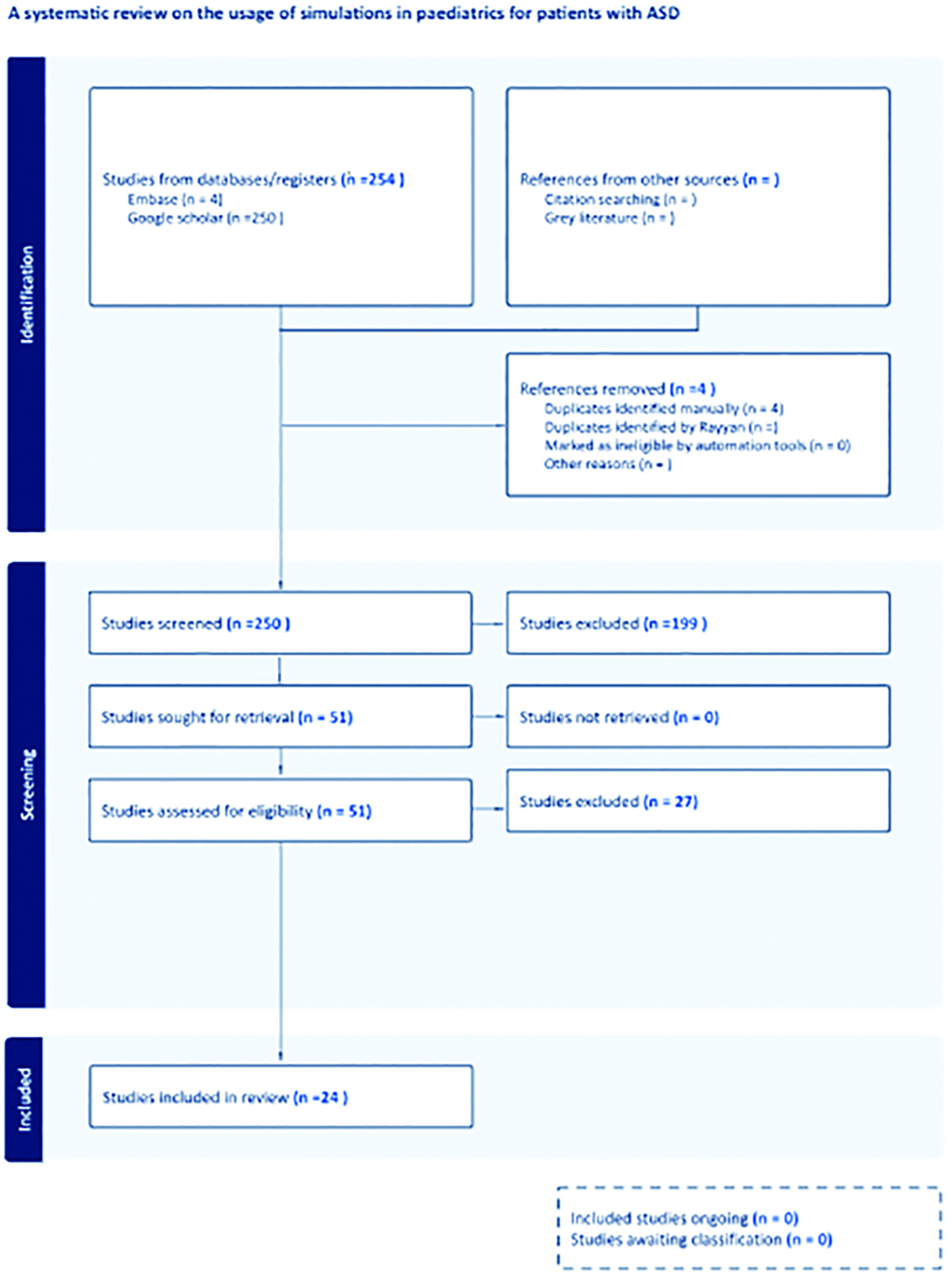

Individuals with ASC experience poorer health outcomes globally, yet healthcare professionals often lack adequate ASC knowledge [1]. Simulation-based learning enhances recall and practice [2], though resource limitations often restrict its use. Mental health nursing simulations are less developed compared to other fields, leaving a gap in training. Our co-created 360-degree video aims to address this by providing realistic scenarios that enhance students’ empathy and confidence in working with ASC patients.

This research aimed to co-create real-time scenarios filmed in 360-degree video to help students understand how a person with ASC experiences hospital admission or clinical procedures. Working with qualified nurses and individuals with lived experience, we developed a 360-degree video of an ASC patient being assessed in a hospital setting. The video was embedded in a Complex Health Care teaching unit and viewed by third-year nursing students using Oculus Quest™ devices. Data were collected via an online survey and focus group discussions (with students and staff) and thematically analysed [3]. Ethical clearance was obtained from our university’s ethics committee.

Eighty students responded to our survey (32% response rate), with 65% reporting no prior ASC training. Seventy-four per cent found the VR resource useful, and 66% felt it would benefit their clinical practice. The small sample size is a limitation, and responses may not be fully representative of the broader student population. Ongoing focus group analysis suggests that the VR exercise helps increase students’ confidence, knowledge, and empathy, as evidenced by comments like: “This was excellent as it put you in the shoes of someone with ASC.” Staff facilitators provided insights into running VR sessions with large cohorts, including the need for preparatory and debriefing sessions, managing background noise, appropriate staff-to-student ratios, and addressing students entering the session late.

This study highlights a significant educational gap, with many students lacking prior ASC training. The positive response to the VR experience suggests it can improve understanding, empathy, and confidence, which may translate to better clinical interactions with ASC patients. Facilitators also identified key considerations for optimizing VR sessions, such as session preparation, managing group dynamics, and debriefing for knowledge consolidation and reflective practice. These findings have implications for nursing education policies, emphasizing the need for structured VR training in mental health curricula. Future research should explore the long-term impact of VR training on knowledge retention and clinical practice, as well as best practices for large-group VR training.

As the submitting author, I can confirm that all relevant ethical standards of research and dissemination have been met. Additionally, I can confirm that the necessary ethical approval has been obtained, where applicable

1. Corden K, Brewer R, Cage E. A Systematic Review of Healthcare Professionals’ Knowledge, Self-Efficacy and Attitudes Towards Working with Autistic People. Rev J Autism Dev Disord. 2022 Sep 1;9(3):386–99.

2. Singleton H, James J, Falconer L, Holley D, Priego-Hernandez J, Beavis J, et al. Effect of non-immersive virtual reality simulation on Type 2 diabetes education for nursing students: a randomised controlled trial. Clin Simul Nurs. 2022;66:50–7.

3. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101.

Internal QR funding received for this research.

Kirsty Duncan 1, Olivia Cole 1, Rose Edwards 1

[1]

38% of LGBTQIA+ individuals report negative experiences within healthcare in the United Kingdom [1], yet no mandatory LGBTQIA+ training exists for NHS staff post-qualification. Simulation-based training can provide a platform to promote culturally competent LGBTQIA+ care [2]. University Hospitals Dorset developed a livestream simulation to increase healthcare staff access to LGBTQIA+ education, with the aim of improving staff confidence in communicating with LGBTQIA+ people.

The simulation was co-produced with LGBTQIA+ community members as knowledge experts with lived experience, including a Transgender woman contacted through the hospital’s Pride Network. The simulation was live streamed via Microsoft Teams from the simulation suite with 40 multiprofessional healthcare staff and students attending online, through voluntary self-selection. Two students participated in the simulation using a high-fidelity manikin voiced by a transgender woman. The scenario focused on pre-operative care, including pregnancy testing, sex assigned at birth, pronouns, and bed allocation in the context of single-sex bays. A facilitated debrief involved in-person participants, online participants through a monitored Teams chat and LGBTQIA+ contributors including a Transgender woman. Online pre- and immediate post-simulation questionnaires captured participant self-assessment and feedback for mixed-method evaluation focusing on accessibility and impact on staff.

Accessibility - 87.5% reported this as first time attending LGBTQIA+ training. Rated as easy to engage with, useful and recommendable. Participants included nurses, physicians, administrators, educators, students, OPDs and child health. 27 of 40 online participants actively communicated via Microsoft Teams chat.

Confidence - Increased confidence communicating with LGBTQIA+ individuals’ post-session. Valued knowledge experts openly sharing feelings and lived experiences.

Qualitative feedback indicated increased awareness of emotional impact of assumptions and importance of open, person-centred communication.

Reported online participant disclosed transgender status to peers post-session.

This project addressed a training gap through accessible simulation that attracted multiprofessional attendees, demonstrating relevance across diverse roles, and increased staff confidence in communicating with LGBTQIA+ individuals. Participants valued the inclusion of diverse faculty and LGBTQIA+ experiences, highlighting the importance of co-production and collaborative facilitation from knowledge experts with lived experience. Feedback from 25% of participants provided valuable insights, and future efforts will focus on increasing response rates for online sessions. Faculty expressed concern about potential incivility in the online format, however none arose likely due to the voluntary session attracting people sensitive to the topic. Research into the process and impact of engaging healthcare staff who would not typically volunteer for such sessions would be valuable.

As the submitting author, I can confirm that all relevant ethical standards of research and dissemination have been met. Additionally, I can confirm that the necessary ethical approval has been obtained, where applicable.

1. Government Equalities Office. National LGBT Survey: Research report. Government Equalities Office; 2018. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/national-lgbt-survey-research-report Accessed 15 April 2025.

2. Pittiglio L, Lidtke J. The use of simulation to enhance LGBTQ+ care competencies of nursing students. Clin Simul in Nurs. 2021;56:133–136. doi: 10.1016/j.ecns.2021.04.010.

This project would not have been possible without the technical expertise of Thomas Randell-Turner, Andrew Lawrence and Sam Pask.

Shiv Vohra 1, Nicholas Stafford, Hermione Tolliday, Matthew Williams

[1]

All anaesthetic and Acute Care Common Stem (ACCS) trainees are expected to undergo an Initial Assessment of Competence (IAC) during the first 3 to 6 months of their anaesthetic training. The umbrella term ‘novice anaesthetist’ is used to describe an anaesthetist in training yet to achieve their IAC.

As per the Royal College of Anaesthetists, one of the two core learning outcomes of the IAC is to provide general anaesthesia for American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) I/II patients having uncomplicated surgery [1,2].

A new regional two-day simulation course was developed to enhance novice anaesthetists’ preparedness and confidence during their IAC period. The broader aims of the course were to improve equity of access to and ensure sustainability of simulation training for novice anaesthetists across the region.

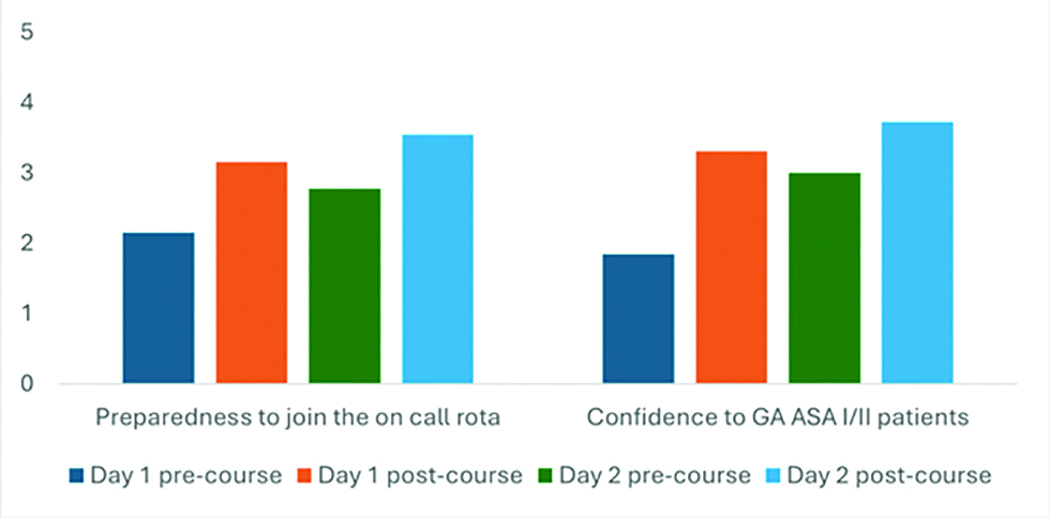

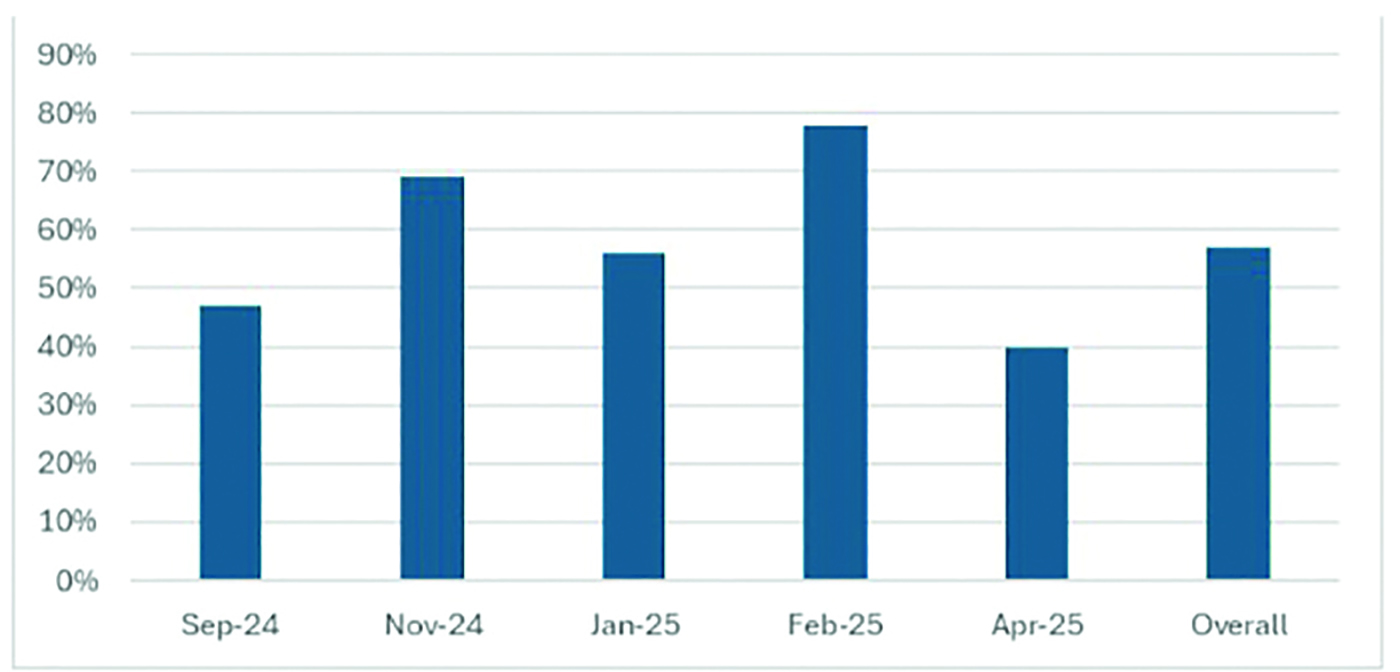

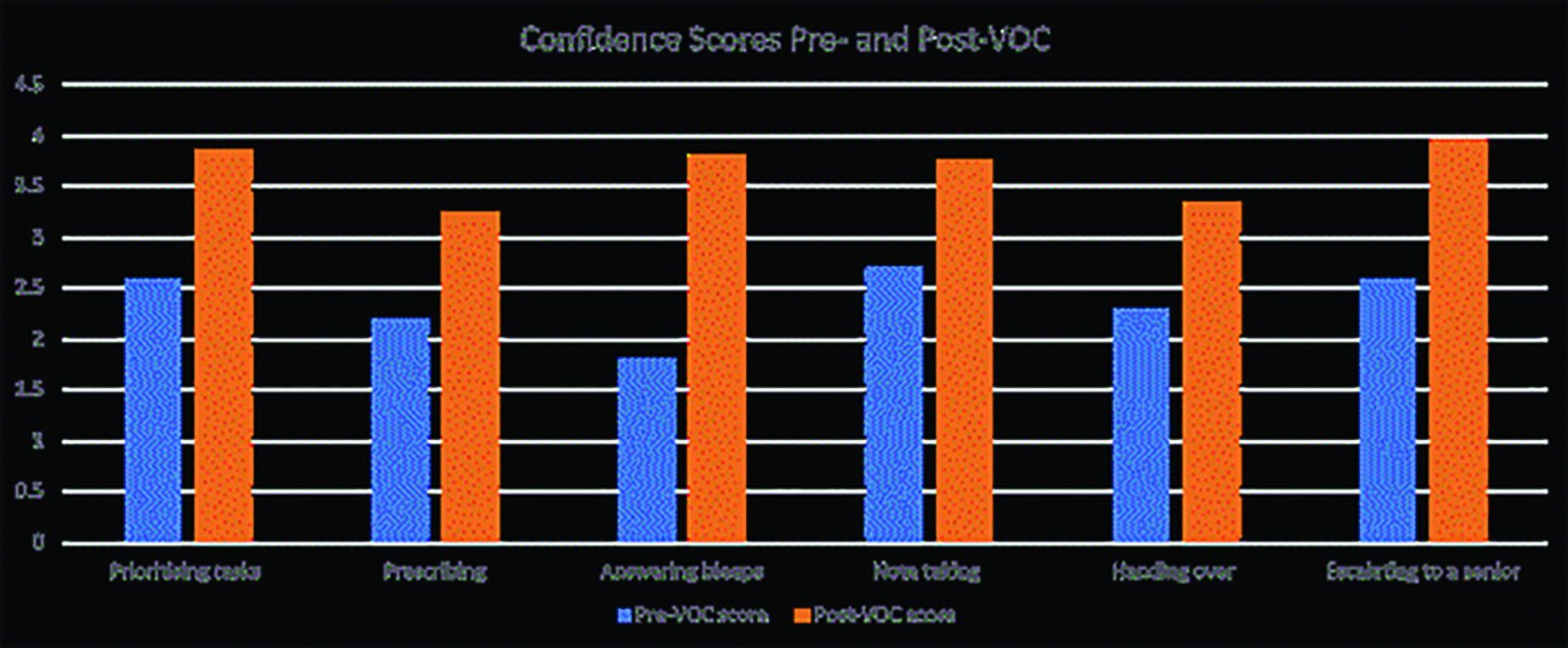

The course was delivered to two cohorts of novice anaesthetists in September 2024 (August 2024 intake) and February/March 2025 (February 2025 intake). Participants engaged in structured simulation scenarios across two days, targeting key anaesthetic competencies including both technical and non-technical skills. Preparedness to join the anaesthetic on-call rota and confidence in managing ASA I/II cases were assessed via pre- and post-course surveys, using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = not at all prepared/confident; 5 = very well prepared/confident). Post-course evaluation of educational value, scenario quality, facilitation, and facilities was conducted, alongside collection of qualitative feedback.

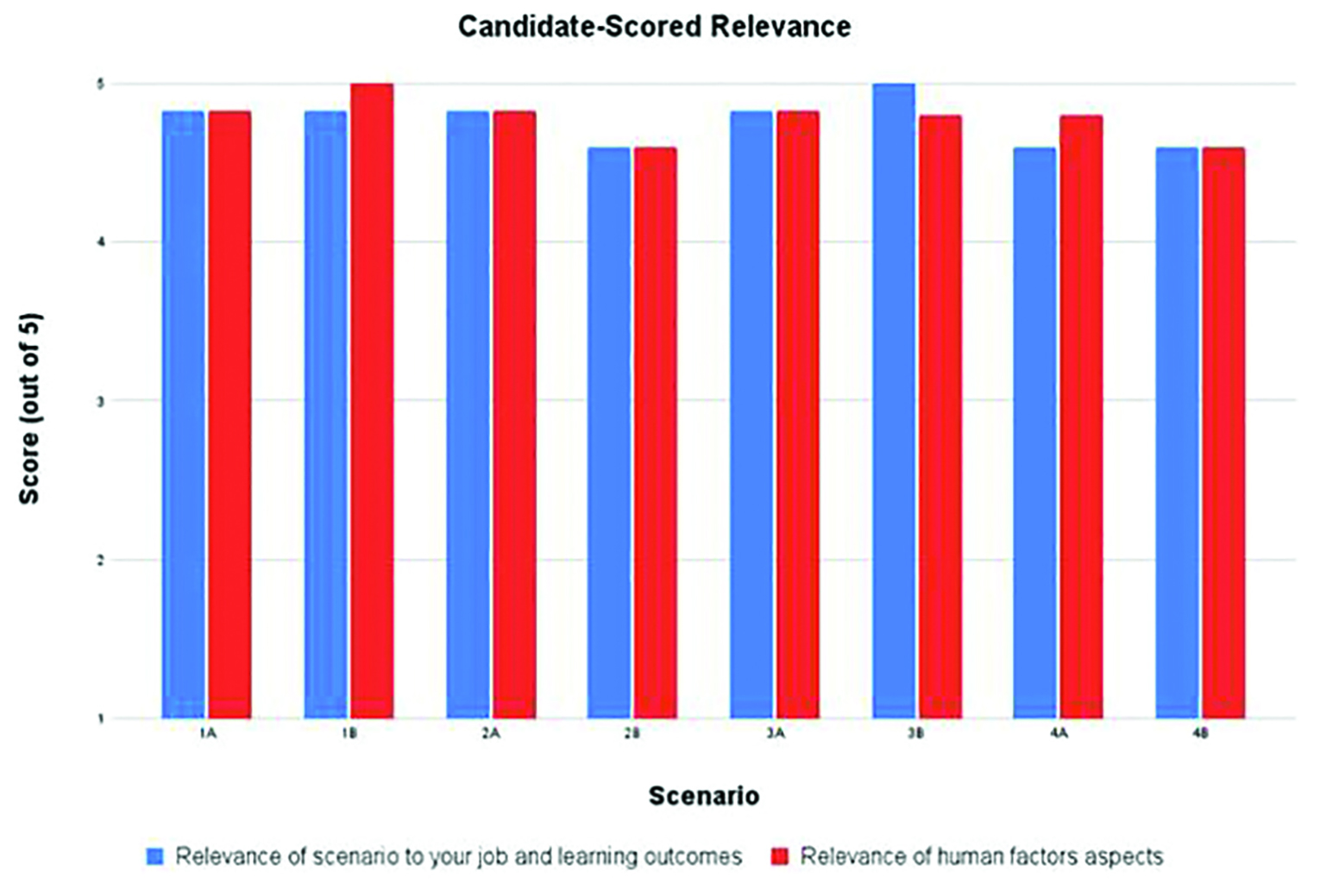

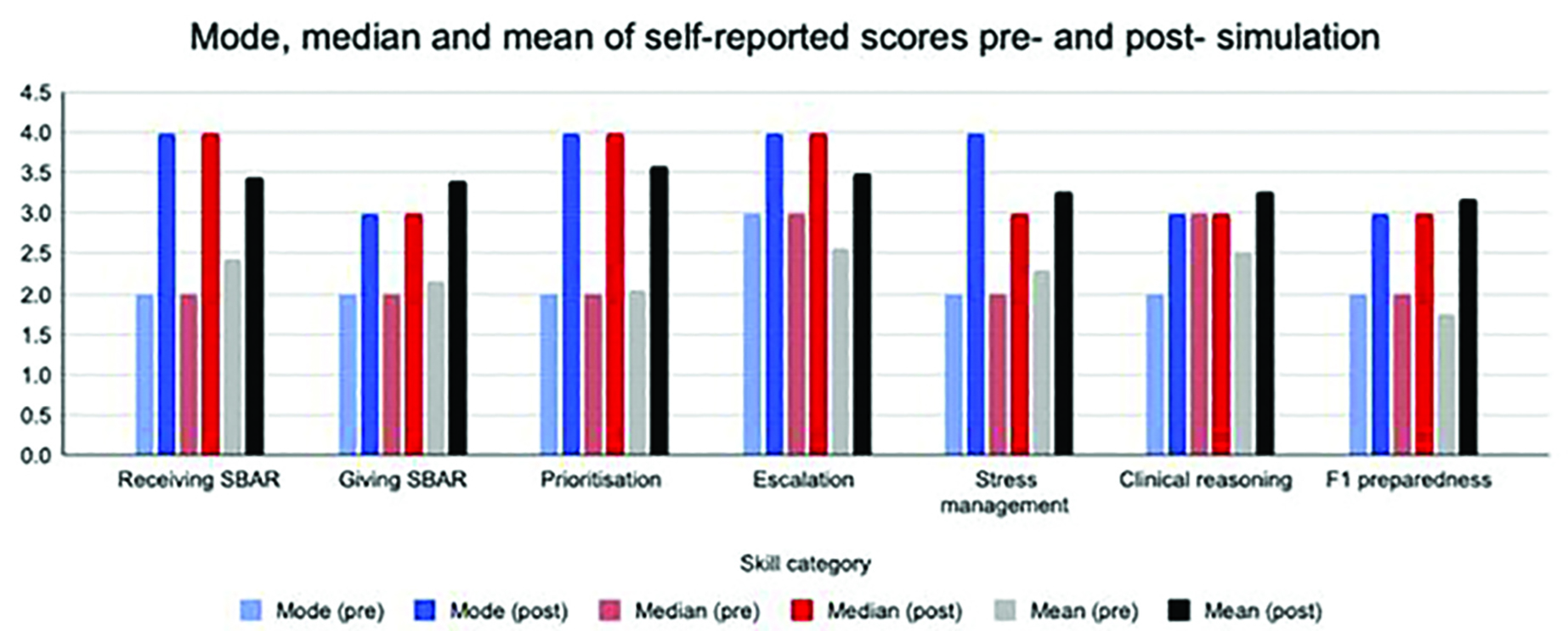

Analysis demonstrated a consistent increase in self-reported preparedness and confidence following course completion as shown in Figure 1.

The majority of participants rated educational value, clinical relevance, and facilitation quality as excellent (scores of 4 or 5).

Qualitative responses highlighted the benefits of scenario variety and the supportive learning environment provided by the faculty.

Participation in a structured regional simulation course significantly improves novice anaesthetists’ preparedness and confidence during the IAC period.

Future work should examine longitudinal outcomes, including impact on clinical performance and progression, and consider evolving the course to incorporate contemporary anaesthetic techniques such as total intravenous anaesthesia (TIVA) [1,2].

As the submitting author, I can confirm that all relevant ethical standards of research and dissemination have been met. Additionally, I can confirm that the necessary ethical approval has been obtained, where applicable.

1. Royal College of Anaesthetists. Entrustable Professional Activities (EPAs) for Anaesthetic Training: EPA 1 & 2 v1.2. 2022. Available from: https://www.rcoa.ac.uk/sites/default/files/documents/2022-09/EPA-1-2-2022%20v1.2.pdf

2. Royal College of Anaesthetists. Guidance for Simulation-Based Education in Anaesthesia Training v1.0. 2024. Available from: https://www.rcoa.ac.uk/sites/default/files/documents/2024-11/Guidance%20for%20Simulation-based%20education%20in%20anaesthesia%20training_v1.0_Nov_2024.pdf

The Simulation Centre team, Quad Centre, Queen Alexandra Hospital, Portsmouth

All faculty members from Hampshire Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust and Portsmouth University Hospitals NHS Trust

Bar Chart Showing Pre- and Post-course Scores for the Novice Anaesthetic Simulation Course

Iman Denideni 1

[1]

Foundation Year 1 (FY1) doctors are unlikely to have firsthand experience of navigating the unique chaos of a Medical Emergency Team (MET) call before joining the team. Experiential learning through simulation could help to bridge this gap between theory and practice [1].

The aim of this simulation project was to provide a realistic view of a MET call from the FY1 perspective. The simulation scenarios progressed in real-time, to uncover hidden internal pressures caused by delayed access to crucial information. They also replicated some logistical challenges commonly encountered by MET members, such as locating necessary equipment in an unfamiliar environment.

Three groups of eight final-year medical students participated in a simulated on-call shift in which they were alerted to a medical emergency (septic shock) using a high-fidelity simulation suite. Psychological safety was maintained by the inclusion of a ‘medical registrar’ acting as team leader. Participants were delegated common tasks undertaken by an FY1, such as establishing intravenous access, obtaining a blood gas, scribing, etc.

Participants had been pre-briefed that all tasks must be completed accurately in real-time. The scenario ran for thirty minutes, followed by a structured debrief addressing human factors [2]. The students repeated the experience a month later with a different clinical scenario (hypoglycaemic seizure). Anonymous reflective questionnaires were collected after each scenario.

Free-text answers from the first (n=23) and second (n=19) questionnaires were analysed for recurring themes [3]. Participants appreciated that their first exposure to the unique pressures of working in a MET was in a safe, simulated environment.

Working in real-time made the scenario feel more realistic but introduced uncertainty and time-pressure that had to be managed. 96% of respondents underestimated the time required to complete their tasks in a stressful environment, which caused further anxiety.

The first scenario gave participants a frame of reference from which they felt better prepared to approach the second. They also reported a greater appreciation for non-technical skills such as closed-loop communication, time-management, prioritisation and teamwork, and applied these more consciously in the second scenario [2].

Hands-on experience made final-year medical students feel better prepared for attending MET calls as future FY1s. The real-time element highlighted latent human factors, necessitating the application of non-technical skills. This simulation design has potential for use during FY1 induction programmes to safely introduce the challenges of working in a MET.

As the submitting author, I can confirm that all relevant ethical standards of research and dissemination have been met. Additionally, I can confirm that the necessary ethical approval has been obtained, where applicable.

1. Watmough S, Box H, Bennett N, Stewart A, Farrell M. Unexpected medical undergraduate simulation training (UMUST): can unexpected medical simulation scenarios help prepare medical students for the transition to foundation year doctor? BMC Medical Education. 2016 Apr 14;16(1).

2. Pruden C, Beecham GB, Waseem M. Human Factors in Medical Simulation [Internet]. PubMed. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559226/

3. Naeem M, Ozuem W, Howell KE, Ranfagni S. A step-by-step process of thematic analysis to develop a conceptual model in qualitative research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods [Internet]. 2023 Nov 8;22(1):1–18. Available from: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/16094069231205789

Ingrid Bispo 1, Emil Havránek 2, Kristýna Hrachovinová 2, Dominika Králová 2, Marc Lazarovici 3, Carla Sá-Couto 1

[1] Community Medicine, Information and Decision Sciences Department (MEDCIDS), Faculty of Medicine,

[2]

[3]

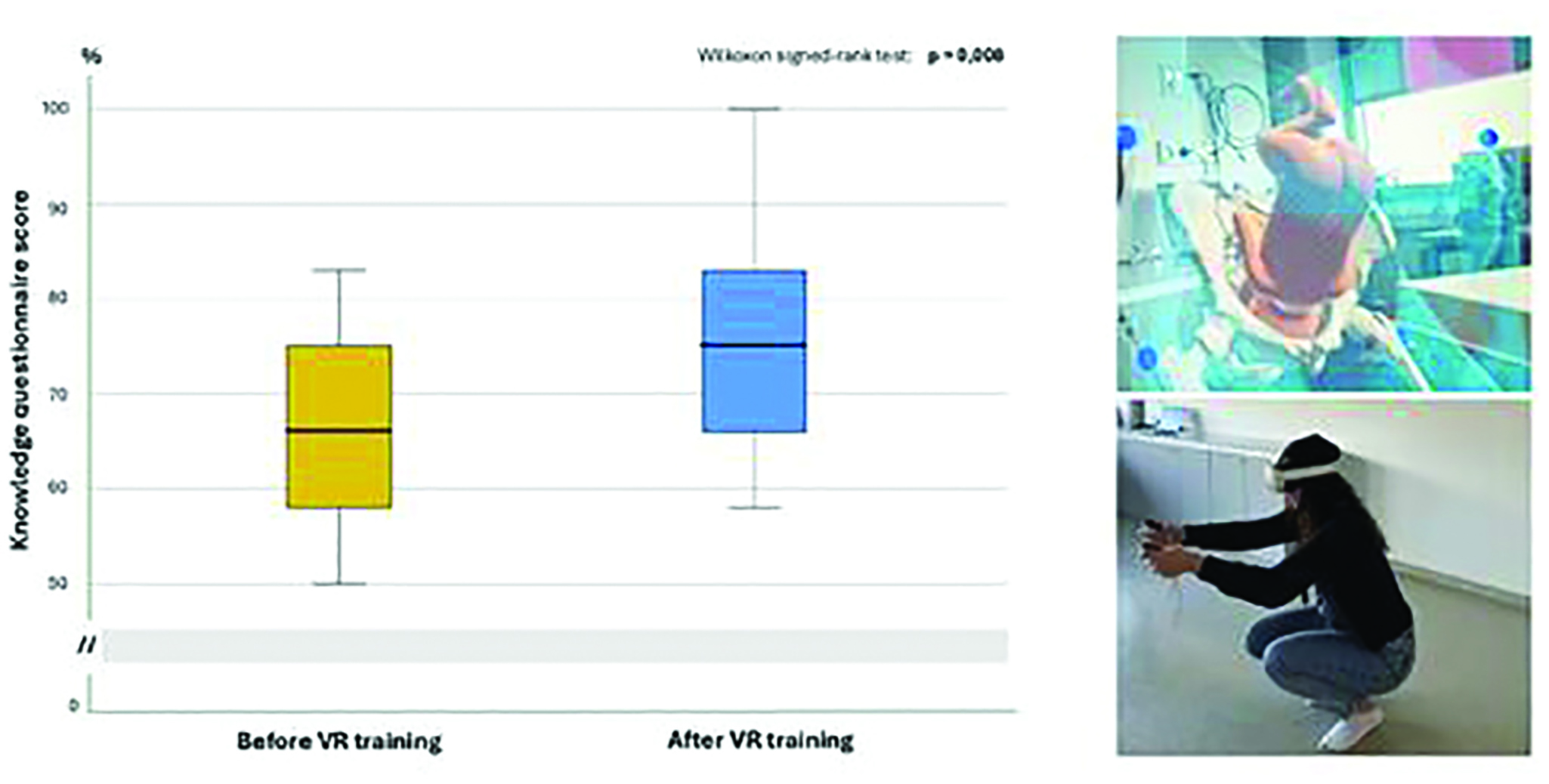

Current midwifery curricula often lack adequate training in optimal positioning techniques for pregnant women, a critical factor for ensuring safe labour outcomes. Evidence from other disciplines [1,2] strongly suggests that enhanced visualization techniques significantly improve proficiency, accelerate learning, and deepen understanding. The PROGRESSION project, funded by the Erasmus+ program, aims to develop a VR-based learning concept to visualize and train positioning maneuvers while illustrating the subtle movements of internal anatomical structures. This study aimed to assess the educational impact of PROGRESSION on midwifery students’ knowledge. Additionally, the usability of the system was also evaluated.

This pre-post-test study was conducted with second-year midwifery students in the Czech Republic as part of their regular 3-year curriculum. Students’ knowledge of maternal positioning during labour was initially assessed using an online questionnaire consisting of 10 clinical case-based questions. Approximately two weeks later, students participated in a 4-hour VR-based training session, held in groups of four. Prior to the session, students were given time to familiarize themselves with the VR technology.

The practical VR training included two hours of self-training on basic labour positioning techniques, followed by two hours of facilitated training during which each student engaged in a clinical scenario and received structured feedback. At the end of the training, knowledge was reassessed using the same questionnaire, with the order of questions and answers shuffled to minimize recall bias. Additionally, students evaluated the usability of the VR system using the System Usability Scale (SUS) [3].

The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of the Faculty of Medicine of Masaryk University, and informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Nineteen midwifery students participated in the study. Students’ knowledge significantly improved following the VR-based educational experience compared to baseline (p=0.008), with a median increase in scores of approximately 10% (Figure 1). Regarding usability, twelve students (63%) rated the VR system above average according to the SUS scoring system (Score≥68).

Midwifery students demonstrated improved knowledge following the VR-based educational experience. By enabling the visualization of pelvic anatomical structures and interactive positioning of the pregnant woman, this approach appears to be a promising tool for enhancing students’ skills in maternal positioning during labour and ultimately promoting safer maternal care. Furthermore, the positive usability ratings suggest that the system is well accepted by students, supporting its further development and future integration into midwifery education.

As the submitting author, I can confirm that all relevant ethical standards of research and dissemination have been met. Additionally, I can confirm that the necessary ethical approval has been obtained, where applicable.

1. Kyaw BM, Saxena N, Posadzki P, et al. Virtual reality for health professions education: systematic review and meta-analysis by the Digital Health Education Collaboration. J Med Internet Res. 2019;21(1). doi: 10.2196/12959.

2. Smelt J, Corredor C, Edsell M, Fletcher N, Jahangiri M, Sharma V. Simulation-based learning of transesophageal echocardiography in cardiothoracic surgical trainees: A prospective, randomized study. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015 Jul;150(1):22–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2015.04.032. Epub 2015 Apr 23.

3. Brooke J. Usability Evaluation in Industry. CRC Press; London, UK: 1996. SUS-A quick and dirty usability scale; pp. 4–7.

The authors would like to acknowledge the team of professionals from the Faculty of Medicine of Masaryk University who also contributed to this study: Barbora Ježková, Matěj Anton, Marika Bajerová, Lukáš Hruban, as well as the students who volunteered their time and effort.

This study is co-funded by the European Union (Erasmus+ KA220 HED Cooperation Partnerships for higher education 2023-1-DE01-KA220_HED-000158531).

Box plots showing midwifery students’ knowledge levels before and after the VR-based educational experience. On the right, illustrative images of the VR training environment are presented.

Rachel Cichosz 1, Joseph Wheeler 1, Harjinder Kainth 1, Andrea Adjetey 1, Karishma Mann 1

[1]

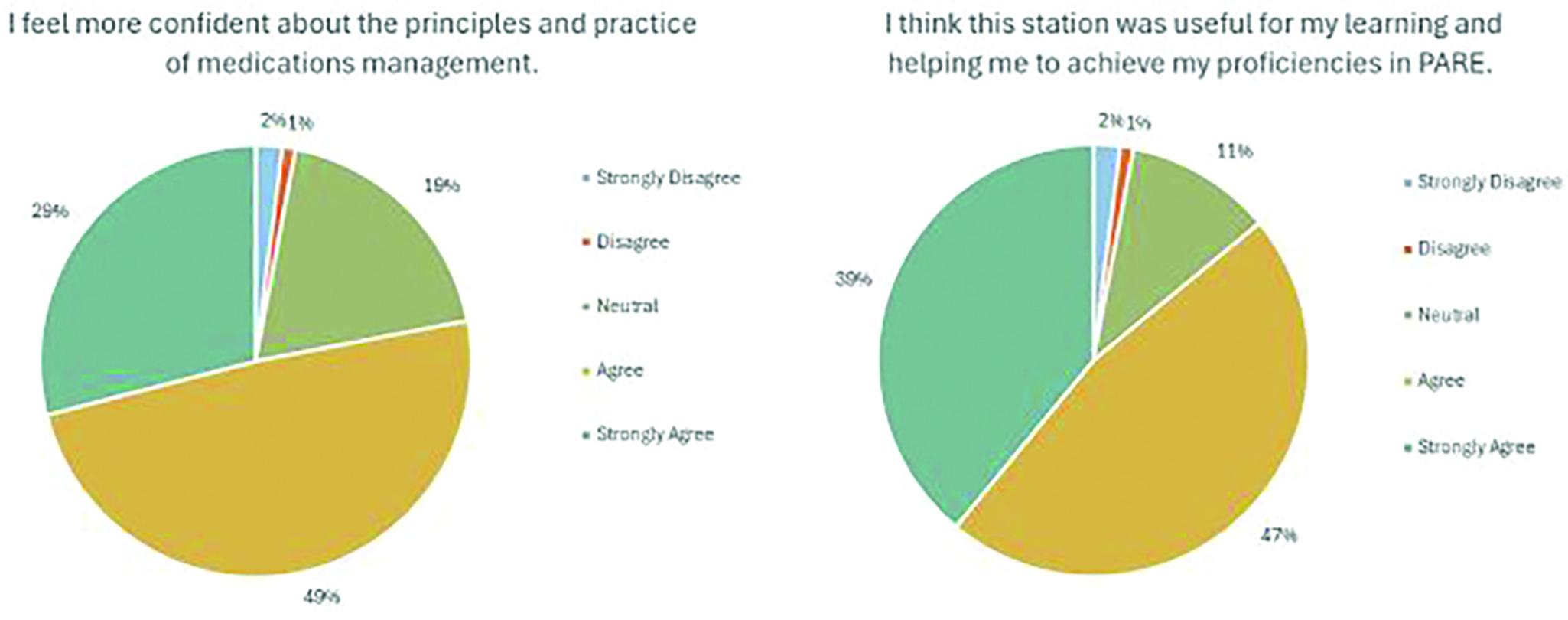

Simulation based education (SBE) is integral to the Internal Medical trainee (IMT) curriculum (1). As a centre, we have developed a run-through series of courses delivered annually to IMT doctors across the region in years 1-7 of their training- IMTSim. The learning objectives for these courses are curriculum mapped and incorporate spiral learning to build on key topics. Data collected through pre- and post- course questionnaires suggest that trainees find our courses enjoyable and beneficial to their professional development. As data on the longer term benefits of SBE is limited, we felt it important to evaluate the ongoing impact of our courses via a ‘one year on’ impact survey.

A ‘one year on’ survey was developed for each of our individual IMT courses, allowing the questions to be specific to learning outcomes at different levels of training, and distributed to all doctors who attended our courses between August 2022 and 2024. Questions focused on the application of candidates’ learning during IMTSim to their every-day practice, and their thoughts on SBE as a whole. Qualitative data underwent thematic analysis by two individuals. Quantitative Ordinal Likert scale data was analysed using non-parametric statistical tests.

‘On the day’ surveys showed a significant difference in pre- and post-course ratings of knowledge of human factors, non-technical skills and the role of debriefing, as well as confidence ratings across a range of skills appropriate to specific learning outcomes at different levels of training. Around 200 doctors attend our IMTSim courses each year, and a total of 60 respondents contributed to our follow-up impact survey, with significant numbers reporting use of the skills/ themes explored during our courses in their everyday practice. When asked about SBE as a whole, significant numbers reported that they felt it was more impactful (87%) and more focused on the individual learner (78%) compared to more traditional teaching modalities.

Our data demonstrates immersive simulation has longer term impact on IMT doctors. Learning continued to be retained at one year post-course, with individuals going on to use and implement skills learned within their routine clinical practice.

As the submitting author, I can confirm that all relevant ethical standards of research and dissemination have been met. Additionally, I can confirm that the necessary ethical approval has been obtained, where applicable.

1. JRCPTB ‘Curriculum for General Internal Medicine (Internal medicine stage 2) training (2022)’. Royal College of Physicians. Available from: https://www.gmc-uk.org/-/media/documents/gim---internal-medicine--stage-2--2022-curriculum-final-july-2022_pdf-91723907.pdf. Accessed 23 April 2025.

Nikki Biggs 1, Alex Jolly 2, Russell McDonald 2, Lorraine Apps 1, Fielding Dave 2

[1]

[2]

WingFactors, a collaboration between aviation professionals and NHS educators, has been working with healthcare simulation faculties since 2020 and with Frimley Park’s Emergency Department (ED) since 2022. Drawing on aviation’s established use of Crew Resource Management (CRM) [1], CRM-trained airline pilots contribute to medical simulation debriefs – an approach that has supported a clearer focus on non-technical skills (NTS). This exposed a lack in NTS-specific training within Emergency Medicine (EM) and positive feedback from clinicians informed the development of a dedicated NTS curriculum and a bespoke training programme.

Our objective was to design and deliver a training programme that strengthened NTS competencies in EM by applying CRM principles and experiential learning in a structured format.

We achieved this by reviewing thousands of non-technical data points from over 100 observed simulations in EDs, and in collaboration with key EM educators, identified 6 core NTS modules: Communication, Leadership, Situational Awareness, Decision Making, Managing Bandwidth and Startle.

We designed each training day to incorporate medical, aviation and abstract simulation to heighten engagement and develop critical thinking and problem-solving skills [2].

The programme was structured around Kolb’s Experiential Learning Cycle [3]- concrete experience, reflective observation, abstract conceptualisation, and active experimentation. A model underpinned in both aviation and healthcare simulation, reinforcing shared learning processes and supporting the transfer of cognitive strategies.

These modules were delivered across three training days with CRM-trained pilots participating as observers and co-debriefers, offering valuable insights into behaviour, communication, and decision-making under pressure.

These have been piloted within the Kent, Surrey, and Sussex (KSS) Deanery, with modules paired as follows:

Day 1: Communication and Leadership

Day 2: Situational Awareness and Decision Making

Day 3: Managing Bandwidth and Startle

Feedback was overwhelmingly positive, with participants noting a greater appreciation for the NTS and the value of cross-industry perspectives:

“Such a valuable opportunity to look at NTS, not just as the ‘afterthought’ they usually are.”

“Very well delivered and lots of thought-provoking content.”

“Great to see human factors applied in a new way—this felt more relevant than some traditional teaching days.”

Nine further training days are planned across the next academic year within KSS, with potential expansion to other regions under review.

This programme illustrates how aviation-derived CRM principles can enhance NTS training in healthcare. Anchored in a shared experiential learning model, it provides a structured, scalable approach to strengthening and developing NTS in medical education.

As the submitting author, I can confirm that all relevant ethical standards of research and dissemination have been met. Additionally, I can confirm that the necessary ethical approval has been obtained, where applicable.

1. Dekker S, Lundström J. From threat and error management (TEM) to resilience. Journal of Human Factors and Aerospace Safety. 2006;12.

2. Kahneman D. A perspective on judgment and choice: Mapping bounded rationality. American Psychologist. 2003;58,697–720.

3. Kolb DA. Experiential Learning Experience as the Source of Learning and Development. Englewood Cliffs, NJ Prentice Hall; 1984.

Jacqueline Driscoll 1, Katie Campion 1, Judith Ibison 1, Jane Roome 2, Holly Coltart 1, Gerard Gormley 3

[1]

[2]

[3]

This study shares phase one results of a two-phase participatory research project that joins simulation faculty (educators), GP trainees (learners), simulated participants (SP’s) and persons with lived experience of chronic conditions (patients) to co-design simulations for primary care. Phase one is concerned with understanding each group’s starting perspectives on, and to surface the tensions within, the current design of simulation scenarios. The purpose is to intervene in the existing epistemic underpinnings of simulation whereby faculty are the primary source of expertise on all aspects including scenario creation and to provide a route map for others on how co-creation can be enacted in this space.

Five focus groups were carried out. Two with patients, (N=10 participants), one with educators, (N=6), one with learners, (N=4), and one with SP’s, (N=5). The data was analysed thematically according to Braun and Clarke [1], with two team members independently coding each transcript before shared final themes generation. One member of the team then ensured all final themes were reflected in each individual’s coding and in each manuscript. Themes were also engaged with via the generation of I-Poems [2]. A reflexive log was kept throughout. Final themes were shared with participants at a co-production event for veracity checking.

Shared concerns across the focus groups included:

1. A desire for realistic scenarios that reflect illness complexity (“GP’s need to look at us holistically” [patient]), whilst recognising the tension between this and standardisation for learners,

2. The desire to improve representation (“we try not to lean into unhelpful stereotypes” [educator]), whilst balancing the importance of pattern recognition for junior trainees, and,

3. A greater emphasis on simulation for improving communication (“body language matters” [SP]).

Differences of opinion arose regarding:

1. How patients can best contribute to simulation practice (scenario creation versus debriefing learners versus briefing actors), and,

2. Concern from educators and trainees about the practicalities and risks of patient involvement (“There’s a danger their personal experience completely confounds everything else” [learner]).

The focus groups surfaced key tensions in current simulation practice with important questions of who is simulation for and what does meaningful safe engagement for all involve rising to the surface? These questions were the starting point for a subsequent co-production workshop with all stakeholders. While neat answers are beyond a single study, our work has advanced the naming of some key considerations for researchers and educators entering simulation co-production.

As the submitting author, I can confirm that all relevant ethical standards of research and dissemination have been met. Additionally, I can confirm that the necessary ethical approval has been obtained, where applicable.

1. Braun V, Clarke V. Thematic Analysis: A Practical Guide. SAGE Publications; 2021.

2. Edwards R, Weller S. Shifting analytic ontology: using I-poems in qualitative longitudinal research. Qual Res. 2012;12(2):202–17.

This study was funded by the Association of Simulated Patient Educators (ASPE).

Merry Patel 1, Christopher Kowlaski 1, 2, Susannah Whyte 1, Emma Flint 1, J. L. Knight 3

[1]

[2]

[3]

Keeping children safe - by identifying safeguarding risks and taking prompt action - is part of all healthcare professionals’ roles [1]. However, practitioners experience numerous internal and external barriers to acting on suspected neglect - thereby delaying initial safeguarding conversations with parents [2,3].

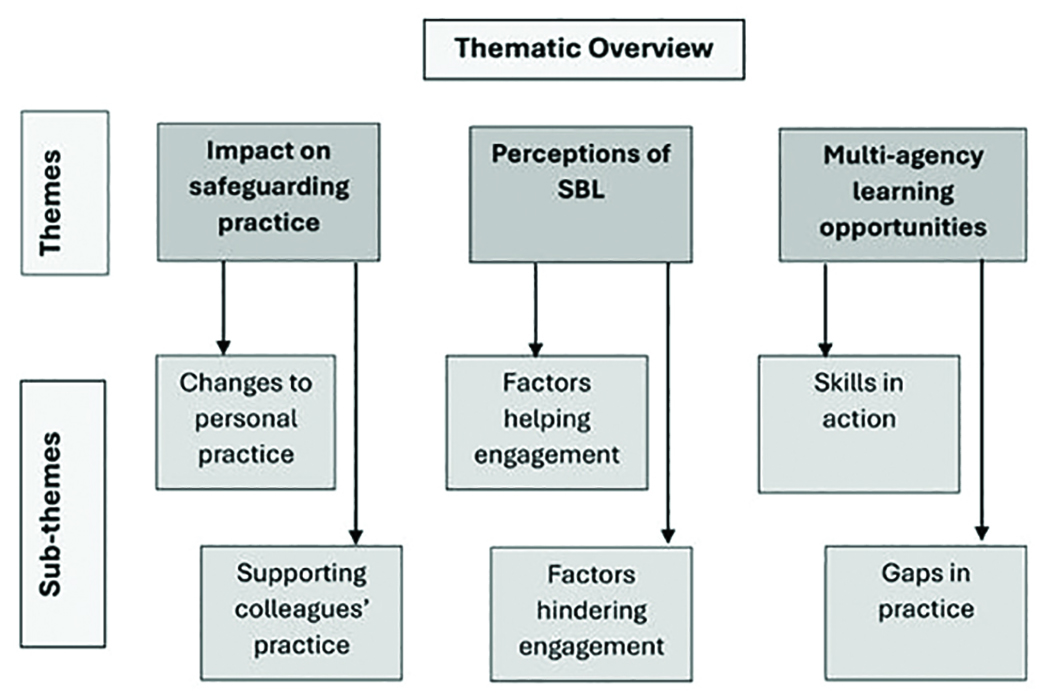

Traditional safeguarding training is largely theoretical in nature - focusing on protocol, professional roles, and the law. Given the complexity of situations when neglect occurs, practical skills in early engagement of parents in safeguarding conversations are essential for safer outcomes for children, as is supporting practitioners to identify barriers to action. This study explored participants’ experience of, and the learning acquired from, a multi-agency simulation training on early childhood neglect.

Practitioners (n=34) from Health, Education, Local Authority and Voluntary Sector services attended a one-day simulation course - ‘Strengthening Practice Around Early Neglect’ (SPAEN). This ran four times (May-July 2024).

Scenarios engaged a simulated parent and a baby manikin and demonstrated increasing levels of physical, emotional, medical and educational neglect over several months.

Course evaluation data was collected with pre-and post-questionnaires - exploring knowledge, confidence and attitudes - and an online evaluation form. Semi-structured interviews were conducted three months post-course.

Analysis of quantitative data was conducted using SPSS Statistics for Windows (v29), and themes and subthemes within the qualitative data were identified using thematic analysis.

Quantitative data (n=34) demonstrated statistically significant (p<0.05) increases in: knowledge of neglect assessment tools; strategies for initiating safeguarding conversations; and confidence in explaining the Early Help process to parents. Online evaluation (n=27) confirmed high levels of engagement in both simulation training (4.96/5, average Likert scores) and multi-agency discussions (4.92/5).

Three overarching themes were identified from the semi-structured interviews (n=6), Figure 1: Impact on personal and team safeguarding practice; Perception of simulation-based learning; and multi-agency learning opportunities. Sustained learning was reported, as were actions being taken to address gaps in practice across agencies following the training.

Multi-agency simulation training is an invaluable tool for exploring uncomfortable conversations around early neglect. Study data demonstrated increasing practitioner knowledge, confidence and attitudes for this complex work and may support earlier conversations around safeguarding concerns. Ongoing opportunities for experiential training of this kind, both at undergraduate and postgraduate levels, is needed to further improve safeguarding practice. These should remain multi-agency in nature wherever possible.

Future involvement of parents and young people would complement course design, bringing greater understanding of parents’ perspectives of uncomfortable safeguarding conversations.

As the submitting author, I can confirm that all relevant ethical standards of research and dissemination have been met. Additionally, I can confirm that the necessary ethical approval has been obtained, where applicable.

1. HM Government (2023). Working together to safeguard children 2023: a guide to multi-agency working to help, protect and promote the wellbeing of children. London: Crown.

2. Lines L, Hutton A. Constructing a Compelling Case: Nurses’ Experiences of Communicating Abuse and Neglect. Child Abuse Review 2021;30:332–46

3. Solem L, Diaz C, Hill L. A study of serious case reviews between 2016 and 2018: what are the key barriers for social workers in identifying and responding to child neglect? Journal of Children’s Services. 2020; 15(1):1–14.

This study was part-funded by an ASPiH 2024-2025 research grant.

Semi-structured interviews: themes and subthemes.

Rebecca Ramsay 1, Sabah Hussain 1, Annabel Copeman 1

[1]

Simulation is a widely acknowledged method of training for healthcare practitioners often with a focus on improving safety and awareness of human factors [1]. Low fidelity in-situ simulation is an efficient way of improving performance [2] and is well established within our NHS trust, with a 30-minute session delivered fortnightly for resident paediatric doctors. Feedback identifies the majority of resident paediatric doctors across the deanery have some, but limited, opportunity to participate in simulation, with a learning gap regarding how to deliver these sessions themselves.

A two-hour session was held for 42 senior resident paediatric doctors to emphasise the value of simulation and teach them how to establish and deliver their own in-situ simulation sessions. This was both lecture-based teaching and a demonstration on how a simulation scenario was run and debriefed. Following this, participants had the opportunity to create their own scenarios in small working groups using a framework to address key points in crisis resource management and technical factors in simulation delivery. A pre- and post-course questionnaire was done to assess confidence in devising, delivering and debriefing simulation sessions using a 5 point Likert Scale from ‘not at all confident’ to ‘extremely confident’.

Pre-course data showed limited exposure to in-situ simulation with 62% of participants having occasional or rare involvement. We also identified reduced confidence levels across creation, delivery and debriefing of simulation. Post-course evaluation demonstrated a significant increase in overall confidence levels reported by 96% of participants. Our results also showed increased confidence of participants in all the specific areas evaluated. Participants rating extremely confident or very confident increased from 12% to 60% in devising, 17% to 68% in running, and 19% to 64% in debriefing an in-situ simulation session.

This highlights the impact a simple teaching session can have on empowering resident doctors with the knowledge to implement simulation practices in their own workplaces. Continuing to address this learning gap at resident doctor level, by providing ongoing teaching in simulation practices, will hopefully continue to improve confidence in delivering and increase use of in-situ simulation training throughout paediatric departments within the deanery, forwarding a culture of change in education practices to benefit a larger cohort of future resident paediatric doctors throughout their training. Our post-course evaluation also identified the need for additional teaching in the art of debrief and therefore has allowed us to plan a further teaching session to cover this.

As the submitting author, I can confirm that all relevant ethical standards of research and dissemination have been met. Additionally, I can confirm that the necessary ethical approval has been obtained, where applicable.

1. Aggarwal R, Mytton OT, Derbrew M, et al Training and simulation for patient safety. BMJ Quality & Safety 2010;19:i34-i43

2. Norman G, Dore K, Grierson L. The minimal relationship between simulation fidelity and transfer of learning. Medical Education. 2012;46:636–647.

Pooja Kamath 1, Ritu Gupta, Shveta Kajal, Gemma Cash

[1]

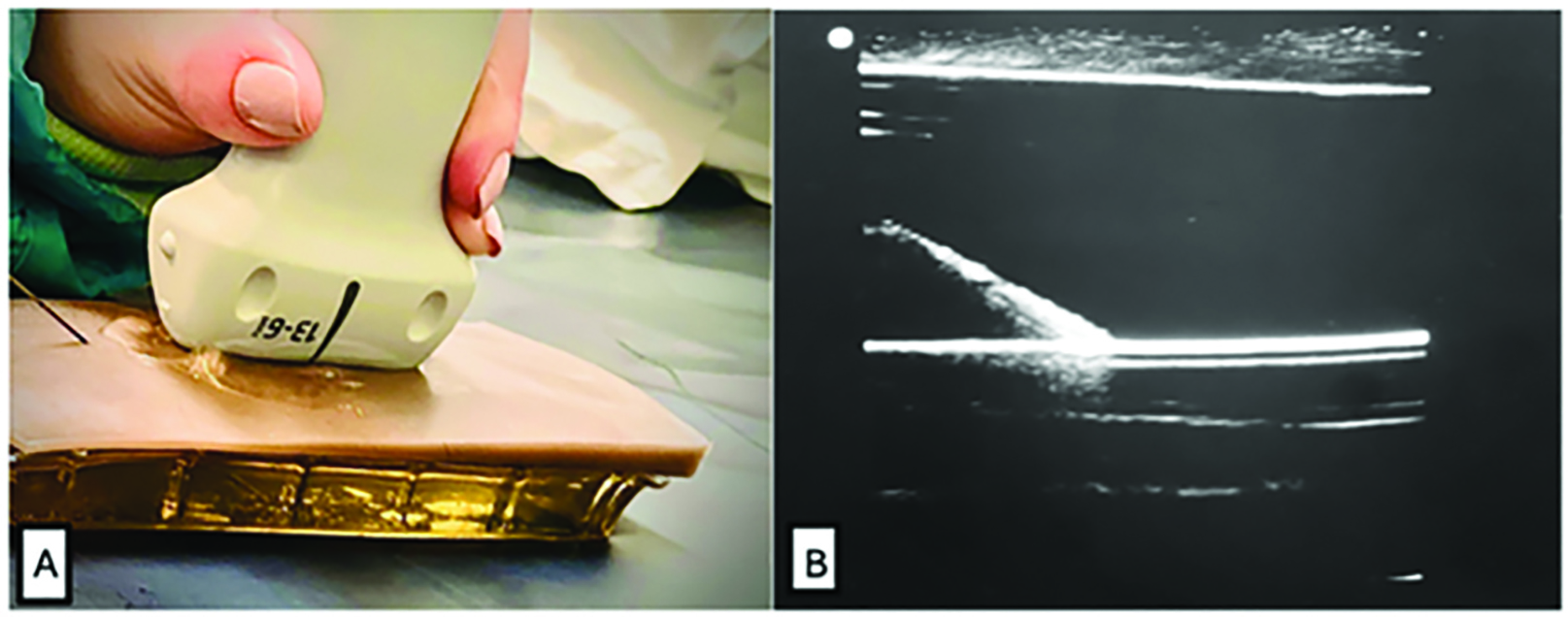

Ultrasound (USS) guided regional anaesthesia is a core skill in anaesthetic training. However, access to high-fidelity phantoms is often restricted by cost. Simulation-based training is well recognised for improving clinical performance [1] and low-cost phantoms offer significant educational value [2]. We developed an affordable, realistic, and reusable gelatine-based phantom in collaboration with the simulation team at our hospital. We evaluated its effectiveness through user feedback across different training levels.

The aim of our project was to assess the educational value, realism and usability of a low-cost USS Needling phantom that we developed in-house, amongst anaesthetic trainees and consultants. The phantom was made using gelatine, glycerine, silicon tubing (to simulate nerves or vessels), and a silicone skin to mimic anatomical realism as seen in Figure 1. It was used in a hands-on training workshop conducted in October 2024 with anaesthetic trainees (ST1-7), clinical fellows and consultants. Post workshop feedback was collected through surveys with questions focusing on realism, needle feel, ultrasound clarity and overall training value.

Our gelatine models were successfully used for ultrasound imaging and needling practice for cannulation and nerve blocks. Feedback was given by anaesthetists across on clarity, realistic resistance and educational value, with 96% (25/26) of respondents rating the model as a useful tool for needling practice. The selected combination of ingredients resulted in a model with excellent needle visibility, minimal track mark retention, and ease of ultrasound use, all while maintaining structural integrity and durability. The total cost of consumable materials for a single model was under £40, making it an affordable training tool. Additionally, our models are reusable and can be stored in the freezer for up to six weeks, then thawed for reuse without compromising quality.

Over the past decade, USS has become an indispensable tool in anaesthesia and intensive care, with NICE guidelines recommending its use for procedures such as central venous cannulation and peripheral nerve blocks. However, gaining competency in USS imaging and needle visualisation can be challenging.

Our model is an affordable, reusable, durable, and high-functional fidelity alternative to both existing gelatine models and expensive commercial phantoms. It provides a practical solution for ultrasound training in anaesthesia and critical care, and other junior trainee doctors in various specialities, ensuring accessibility without compromising educational value. The model also aligns with national curriculum goals on USS proficiency [3]. Feedback from trainees and experienced clinicians highlights its strong educational impact.

As the submitting author, I can confirm that all relevant ethical standards of research and dissemination have been met. Additionally, I can confirm that the necessary ethical approval has been obtained, where applicable.

1. McGaghie WC, Issenberg SB, Cohen ER, Barsuk JH, Wayne DB. A critical review of simulation-based medical education research: 2003–2009. Med Educ. 2010;44(1):50–63.

2. Walsh CD, Ma IWY, Eyre AJ, et al. Implementing ultrasound-guided nerve block in the emergency department: A low-cost, low-fidelity training approach. AEM Educ Train. 2023;7(5):e10912.

3. Royal College of Anaesthetists. 2021 Curriculum: Learning syllabus – Stage 3: Regional Anaesthesia.

Stephen Ojo 1

[1]

Simulated patients (SPs) are widely used in healthcare professions education (HPE) to enhance experiential learning, support assessment, and provide realistic, safe environments for developing clinical and communication skills [1,2]. Despite the acknowledged value of SPs in simulation-based education, there is limited consensus on what constitutes effective SP training [3]. The absence of standardised curricula raises concerns about consistency, educational outcomes, and quality assurance. This scoping review sought to explore: What does current literature reveal about the content, methods, and gaps in SP training within HPE?

A systematic scoping review was conducted following the PRISMA-ScR guidelines. Six electronic databases (MEDLINE, PubMed, CINAHL, Scopus, Web of Science, Cochrane Library) and grey literature were searched for English-language studies published up to May 2023. Studies were screened for relevance using pre-defined inclusion/exclusion criteria. Eligible sources reported on SP training in HPE. Data were extracted and analysed thematically to identify trends, gaps, and key training components.

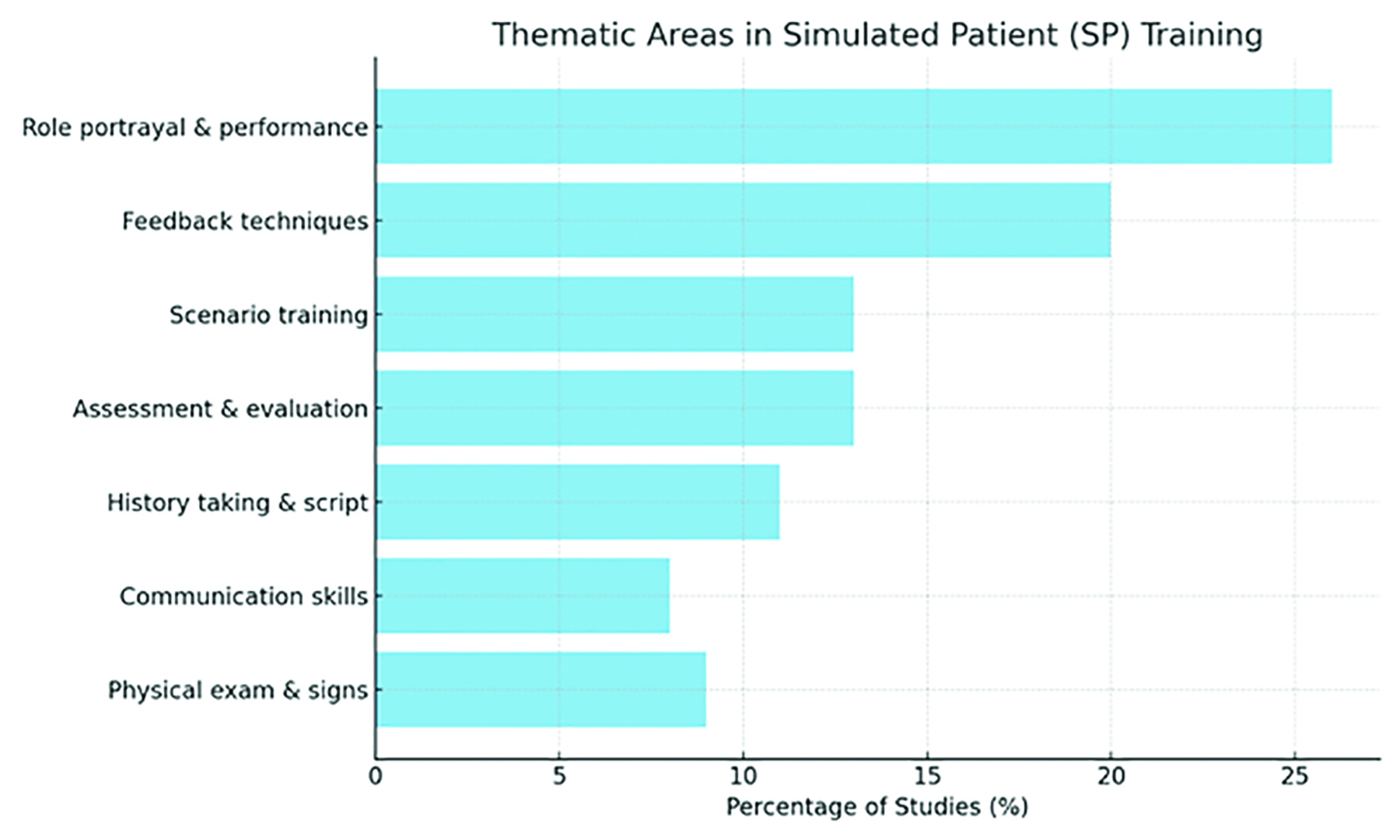

Of the 886 records screened, 25 studies met the inclusion criteria. Thematic analysis identified seven key areas of SP training (Figure 1): role portrayal and performance (26%), feedback techniques (20%), scenario engagement and patient interaction (13%), assessment and evaluation (13%), history taking and scripting (11%), communication skills (8%), and physical examination and signs (9%). Five categories of training methods emerged: structured training sessions, scripted briefs, technology integration, group activities, and observational feedback. Considerable variation in duration, content depth, and assessment methods was noted across studies. No universal framework for SP training was identified.

This review reveals broad variability in how SPs are prepared for simulation roles across institutions. While common training domains exist, there is a lack of standardised curricula, structured assessment tools, and reporting on long-term training outcomes. This variability may limit fidelity, learner experience, and inter-institutional benchmarking. Findings suggest an urgent need for evidence-informed, consensus-driven guidelines to improve SP training quality, consistency, and scalability across HPE.

As the submitting author, I can confirm that all relevant ethical standards of research and dissemination have been met. Additionally, I can confirm that the necessary ethical approval has been obtained, where applicable.

1. Cleland JA, Abe K, Rethans JJ. The use of simulated patients in medical education: AMEE Guide No 42. Med Teach. 2009;31(6):477–486.

2. Nestel D, Bearman M. Simulated patient methodology: theory, evidence and practice. Wiley-Blackwell; 2014.

3. Greene G, Gough S. Train-the-simulated-patient programme: a UK evaluation. Clin Teach. 2015;12(6):403–407.

Michelle Holmes 1, Gary Francis 1, Claire Nadaf 1, Matt Lofthouse 1, Edit Bertalan 2, Jess Burt 2

[1]

[2]

The social care workforce must evolve to meet the changing needs of an ageing population, including increasing demand and delivery of homecare. Current training for home care workers is often theory-based, with homecare workers often feeling underconfident and lacking skills in some areas. Although simulation is widely used in healthcare for skill enhancement, it is underutilised in homecare training. This project aimed to explore the use of simulation-based education to upskill homecare workers to identify risks they may encounter in a client’s home.

This study was a pre-post mixed-methods study. Two high-fidelity simulations were undertaken, one for home care workers and another for home care managers. The simulation sessions were conducted in an activity of daily living suite. Both simulations were pre-briefed, recorded and debriefed using the STOP 5 hot debrief model [1]. Pre- and post-questionnaires included demographics, the 10-item General Self-Efficacy Scale, a bespoke measure on confidence with caring and communicating with clients, and the Student Satisfaction and Self-Confidence in Learning questionnaire [2]. Descriptive statistics were undertaken on pre and post surveys, the debrief was transcribed verbatim and analysed using thematic analysis alongside open-text comments from the questionnaires [3].

12 carers and 8 care managers took part in the simulation sessions. Four themes were developed across the quantitative and qualitative findings. Two themes focused on the use of simulation within home care: “Is Aggie okay?” – Risk Identification and client care, and “We’re in for it here” – Showcasing the challenges and difficulties of care. The other two themes focused on participants’ views on simulation as a training method: “Understanding the proper role of a carer” – Benefits of simulation in training, and “Obviously, we’re in a role play situation” – Challenges in engaging in simulation.

Simulation helped promote client-centered thinking, critical reflection, and peer discussion. It was seen as a useful complement to theoretical training, especially in preparing new carers. However, challenges such as suspension of disbelief, stress, and organisational barriers impacted engagement. To enhance effectiveness and minimise learner anxiety, the study highlights the importance of realistic scenarios, pre-briefing, and debriefing to ensure psychological safety and skill transfer.

As the submitting author, I can confirm that all relevant ethical standards of research and dissemination have been met. Additionally, I can confirm that the necessary ethical approval has been obtained, where applicable.

1. Walker CA, McGregor L, Taylor C, Robinson S. STOP5: a hot debrief model for resuscitation cases in the emergency department. Clinical and experimental emergency medicine. 2020;7(4):259–66.

2. Pence P. Student satisfaction and self-confidence in learning with virtual simulations. Teaching and Learning in Nursing. 2021;17.

3. Braun V, Clarke V, Hayfield N, Terry G. Thematic Analysis. In: Liamputtong P, editor. Handbook of Research Methods in Health Social Sciences. Singapore: Springer Nature; 2019. p. 843–60.

Ghaniah Hassan-smith 1, 2

[1] Aston Medical School,

[2] Queen Elizabeth Hospital Birmingham,

Virtual reality (VR) simulation is emerging as a transformative tool in medical education, offering immersive, clinical experiences on demand. In neurology, VR and augmented reality have been shown to enhance learning of complex concepts such as neuroanatomy [1]. Additionally, immersive simulation paired with structured debriefing can uncover discipline-specific knowledge gaps otherwise difficult to identify [2]. However along with addressing educational needs, limitations including logistic expertise required in deploying VR sessions at scale require further work to demonstrate pragmatic utility of this technology in educating medical students. The work presented here therefore highlights a potential role for use of VR in medical education.

We integrated VR simulation into the undergraduate MBChB curriculum. Over 250 medical students in years 3&4 completed a VR scenario focused on acute bacterial meningitis management using Oculus Quest 2 headsets and Oxford Medical Simulation (OMS) software. Sessions included a structured debrief using the PEARLS framework. Faculty and facilitator reflections were also gathered.