Simulation is a mandatory component of surgical training; the challenge remains to develop ‘close-to-real’ training. Management of paediatric elbow fractures is an obligatory competence for completion of training in Trauma and Orthopaedics. Current methods use dry bone simulation to teach wire configuration, but intra-operative radiographic interpretation is not possible.

This proof-of-concept study aimed to explore a novel three-dimensional (3D) printed model with real-time intra-operative radiographic feedback in the training of orthopaedic surgeons. In conjunction with Axial 3D Printing (Belfast, Northern Ireland), a child’s elbow model was produced with radiopaque ‘bone’ and flexible radiolucent ‘soft tissues’ technology to produce a high-fidelity paediatric elbow model, suitable to be used under fluoroscopic guidance, as an adjunct to teaching Kirschner wiring of a supracondylar fracture. Nineteen orthopaedic trainees participated in simulation training. During the simulation, the participants were assessed using the Objective Structured Assessment of Technical Skills in addition to completion of pre- and post-training surveys.

Positive responses were received regarding the model’s usefulness for simulation training, particularly regarding the highly anatomical radiographic appearances. A 5-point Likert scale was used to evaluate self-confidence in performing the procedure pre- and post-simulation teaching. There was an average improvement in confidence of 1.15 for performing supracondylar K-wiring, following the simulation workshop.

This new 3D printing technique demonstrates a further development in modern surgical training. Sawbones have numerous limitations, while the costs and practicalities of cadaveric training remain prohibitive. By combining realism and low risk, these 3D printed models may offer a solution to these challenges and contribute to enhanced patient care.

What this study adds:

•3D printed models can be used to enhance trauma and orthopaedic simulation training.

•A novel 3D printed model has the capability for real-time radiographic feedback.

•Trainee self-confidence in procedure performance was significantly improved.

Teaching and training in the surgical field has historically had an apprentice-type model whereby trainees operate under senior supervision and guidance, with a ‘see one, do one, teach one’ approach described by Halsted applied to learning [1,2]. Modern surgical education and curriculum changes have shifted away from a time-based expectation, towards competency-based training, emphasizing the demonstration of skill and judgement rather than simply accumulated experience. Alongside this, challenges of surgical training have increased with demands for theatre efficiency leading to denied educational opportunities, increasingly frail and co-morbid patients who are less suitable as teaching cases, and shortages of trainers [3]; therefore, adopting new and innovative methods of training is a necessity. In this context, simulation has become an essential adjunct, and health care has adopted simulation as a controlled learning to supplement clinical ‘on-the-job’ training. Simulation allows a safe and reproducible environment for learners to explore new concepts and skills, creates opportunities which may rarely occur in the clinical setting whilst maintaining patient safety, and provides learning opportunities despite limitations to training hours and patient encounters [4,5]. Consequently, adopting innovative methods such as simulation-based education is a necessity. It is acknowledged that information recall and task-based memory are best applied when rehearsed in scenarios mimicking the workplace [1].

Three-dimensional (3D) printing was originally conceptualized in the 1980s in Japan and has revolutionized manufacturing by minimizing financial burdens and maximizing efficiency. 3D models have been shown to be useful in trauma and orthopaedic surgery as pre-operative planning tools; however, their role in simulation training is less well understood. Research has proven the usefulness of surgical simulation models to increase confidence and skills for medical students and surgical trainees [6].

The aim of this proof-of-concept study was to establish if suitable models could be designed to simulate anatomically specific sites for use in the training of orthopaedic surgeons, with consistency and texture with maximal fidelity to allow radiographic assessment during the simulated scenario. Further innovation using 3D printed models to produce simulated surgical fields and procedures has relevance to training across all grades and specialties, with applications in clinical training to ensure an adequately skilled workforce of the future.

Manipulation and Kirschner wiring (K-wiring) of a paediatric supracondylar elbow fracture was chosen as it’s a mandatory procedure, which requires completion of a minimum number to complete trauma and orthopaedic training. Supracondylar humerus fractures are a common fracture in the paediatric population with a peak incidence between the ages of five and eight. Percutaneous K-wiring is an established technique for stabilising bone fragments to maintain alignment during fracture healing [7].

K-wiring involves appropriate patient positioning, a reduction manoeuvre, and then K-wires are placed through the skin and into the bone with image intensification used throughout to monitor the fracture reduction and guide placement of the K-wires. This task involves techniques and skills to overcome the challenges of a small bony structure presented by a paediatric elbow and a specific optimal starting point for a safe anatomical corridor for the wire to traverse. There are significant soft tissue structures in the surrounding area, and the final position of the wires is critical to the stability of the final wire configuration [8]. By allowing trainees to become confident in the placement of K-wires, through repetition in the controlled simulation environment, this would reduce the mental burden intra-operatively to allow dedicated focus on the challenge of manipulation and holding an adequate reduction at the fracture site.

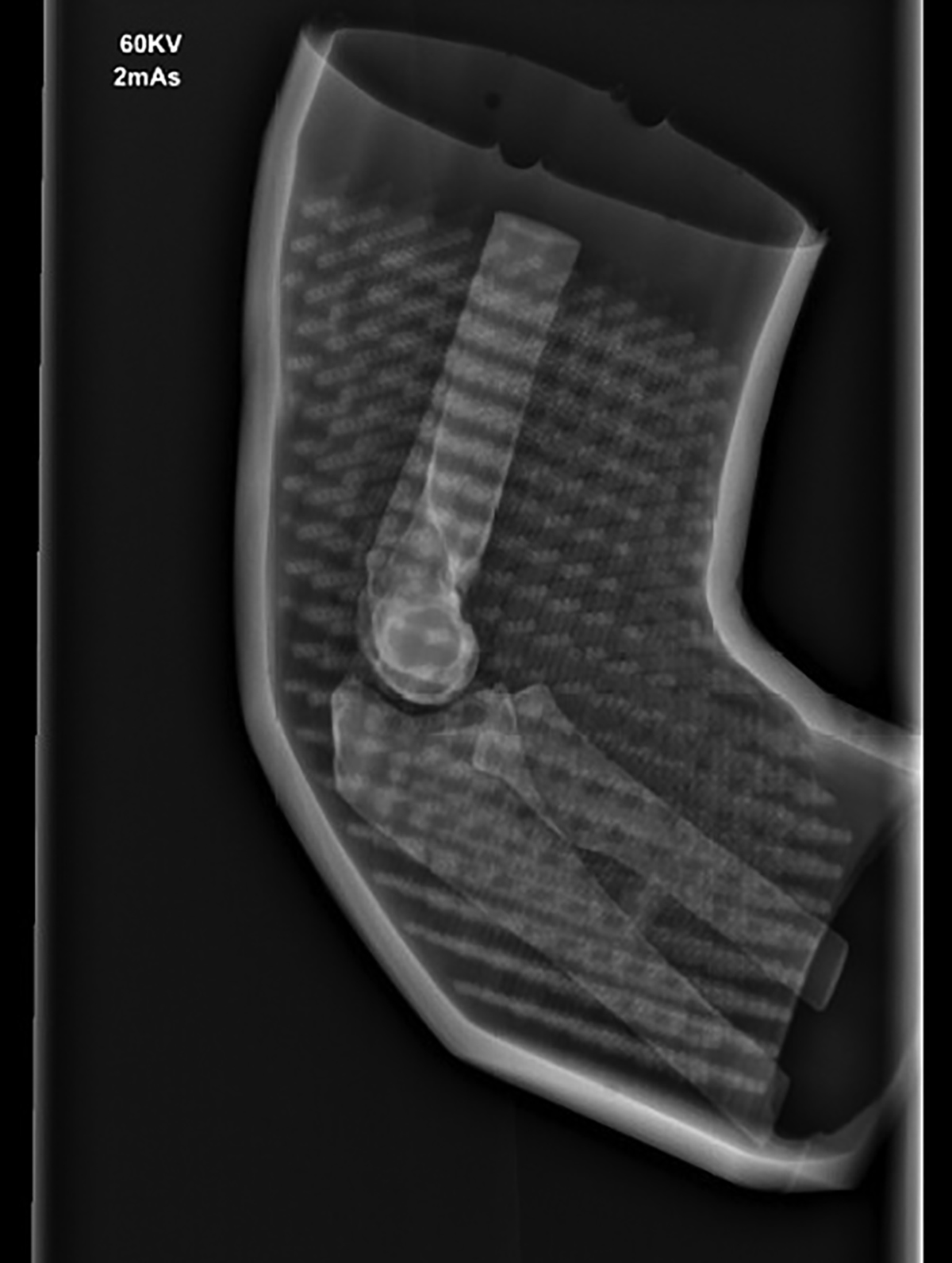

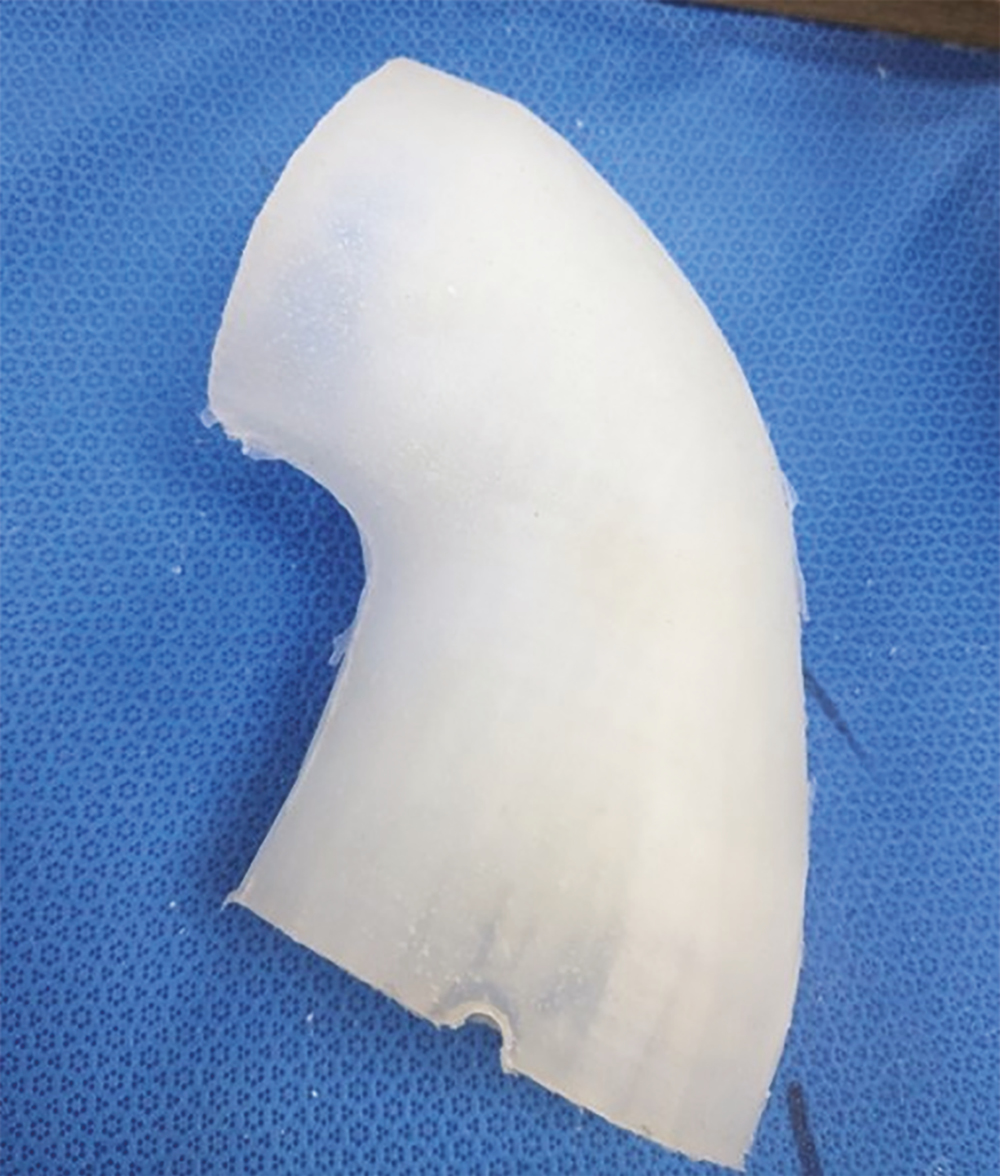

Work towards a simulation 3D model was undertaken in partnership with Axial 3D, an industry-leading, Belfast-based 3D printing company. The research and design process involved collaboration between clinicians and the printing team. Initially, high-quality medical imaging and anatomical data were inputted, followed by ongoing dialogue between the research and design team, facilitating improvements. Multiple prototypes (as seen in Figures 1 and 2) were tested and refined to develop a lattice with an overlying silicone skin to create the flexibility of the elbow joint with the additional advantage of creating an envelope of soft tissues to simulate the overlying swollen tissues of an injured limb (External appearances shown in Figures 3 and 4). A radiopaque material was sourced to improve the model’s radiographic appearance.

All trauma and orthopaedic registrars in the local deanery were invited to be involved in a simulation workshop. Regular simulation training has been incorporated into the local curriculum, and trainees have become familiar with it and its learning value. All those available to attend were included in the sample. The session was led by faculty of consultant surgeons with experience in the management of paediatric trauma. It consisted of a discussion of practical points such as theatre set-up and positioning, to develop participants’ self-confidence in approaching this procedure in the clinical setting, with a quick transition to focus on hands-on learning.

The format of the session lent itself to rotational groups; three trainees worked together to rotate through observing, assisting and performing the procedure. Groups were designed to ensure a spectrum of experience, with repeated exposure, to promote peer learning. During the workshop, each trainee had the opportunity to complete a K-wiring procedure using the model and was dual assessed by a peer and an experienced consultant using the validated Objective Structured Assessment of Technical Skills (OSATS) global rating tool to score against pre-set criteria for specific surgical behaviours [9–12]. OSATS has been shown to be a valid and valuable tool that can overcome variability in operative time and complication rates, heavily influenced by case complexity. This is supported by the work of Robertson et al., showing superior reliability and validity of global rating scores, regardless of assessor training [13,14].

There were four models available for use between the groups; this required multiple procedures to be performed on a single model. Following the workshop, an anonymous online feedback survey was distributed. Google Forms was used as it was a free, easily accessible and intuitive platform. The survey underwent a pilot in advance of the session to ensure satisfactory understanding and time taken to complete. A QR code was displayed to encourage completion of the survey immediately following the session to optimise response quality. A further reminder was distributed to urge the remaining responses to be completed.

All participants wore personal protective equipment in the form of high-quality lead protection for thyroid and body. All unnecessary personnel maintained a safe distance from the radiation source. Ethical approval was sought and obtained from the Faculty of Medicine, Health and Life Sciences Research Ethics Committee (Faculty REC) at Queen’s University Belfast in accordance with the Proportionate Review process (Ref: MHLS 23_138). Statistical analysis was carried out by an experienced statistician and performed using SPSS v29 software (IBM, Armonk, New York, USA). Independent t-tests were used to compare the trainee groups. A P-value <0.05 was considered significant. Content analysis was used to interpret free-text data from surveys.

Initial radiographic appearance of silicone cast

Improved appearance following modifications

Photograph of final model postproduction (Antero-posterior)

Photograph of final model postproduction (Axial)

The current local training programme has 32 trainees and 19 were recruited to complete the workshop. The number of participants at each stage of training is outlined in Table 1.

| LAT3 | 3 (15.8%) |

| ST3 | 4 (21.1%) |

| ST4 | 3 (15.8%) |

| ST5 | 4 (21.1%) |

| ST6 | 1 (5.3%) |

| ST7 | 3 (15.8%) |

| ST8 | 1 (5.3%) |

To allow for comparison, the trainees were pooled into more and less experienced if they had greater than 24 months of registrar-level operating experience. During the simulation model workshops, senior trainees had an average OSATS score of 31.8 compared to the junior trainees, who averaged 27.9, which mirrors real-life expectations. This higher OSATS score for the senior, more experienced operators interacting with the 3D printed model reached statistical significance (P = 0.015). These results are shown in Table 2.

| Junior | Senior | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total OSATs Score (mean, SD) | 27.95 (3.90) | 31.89 (2.09) | 0.015 |

To establish the trainees’ experiences using simulation, previous exposure was explored. Sawbones and arthroscopy simulation technology had been widely used, but newer technology, such as virtual reality (VR) and 3D printing, was in less widespread use (Table 3).

| Low fidelity, for example, box trainer | 7 (41.2%) |

| Arthroscopy simulator | 15 (88.2%) |

| Sawbone workshop | 16 (94.1%) |

| Cadaver or animal specimen | 7 (41.2%) |

| Virtual reality | 2 (11.8%) |

| 3D printed models | 3 (17.6%) |

* Two responses not completed (n = 17).

Participants were asked to self-assess their confidence in the procedure of manipulation under anaesthetic and K-wiring of a paediatric supracondylar fracture, both prior to and following the teaching session with the 3D model. The results are shown in Table 4.

| Pre-teaching | Post-teaching | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 (No confidence) | 4 (21%) | 0 |

| 2 | 5 (26%) | 1 (5%) |

| 3 | 4 (21%) | 2 (10%) |

| 4 | 1 (5%) | 11 (58%) |

| 5 (Very confident) | 5 (26%) | 5 (26%) |

The self-reported confidence scores universally remained static or increased. The average increase was 1.15 following the simulation workshop. When further analysis of the junior (LAT3-ST4) and senior cohorts (ST5+) was performed, the average for the junior trainees showed improved confidence by 1.8 (SD 0.92) compared to the senior trainees, for whom the simulation was less impactful, as they had an improvement of 0.44 (SD 0.73). This difference in improvement reached statistical significance with a P-value of 0.003 (Table 5).

| Junior | Senior | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Difference in confidence (mean, SD) | 1.80 (0.92) | 0.44 (0.73) | 0.003 |

Further questions sought to gather information from the trainees regarding the realism and usefulness of the model as a teaching tool; the results are shown in Tables 6 and 7. Most trainees felt the simulation was neutral or realistic (n = 17, 89.4%). There were no participants who reported it to be very realistic. However, despite this, the overwhelming response regarding the usefulness of the model for training was positive, with 78.9% of trainees describing it as useful or very useful.

| 1 (Not realistic) | 1 (5.3%) |

| 2 | 1 (5.3%) |

| 3 | 8 (42.1%) |

| 4 | 9 (47.4%) |

| 5 (Very realistic) | 0 |

| 1 (Not useful) | 0 |

| 2 | 1 (5.3%) |

| 3 | 3 (15.8%) |

| 4 | 5 (26.3%) |

| 5 (Very useful) | 10 (52.6%) |

Finally, there were questions answered using free text. Key themes included the ability to obtain real-time feedback, the ability to develop 3D orientation and help to develop the skill of using clinical information, and existing wires placed for reference.

Very useful to be able to screen as would in reality.

Good for thinking about amount of XRs taken and thinking about both planes before screening.

Five participants remarked on the usefulness of being able to have direct feedback and advice from consultants to improve surgical technique, such as choosing the correct entry point for the wire insertion, and recognized the safe environment simulation provided.

Gave me confidence to trial techniques knowing that I am not causing harm to a patient.

The feedback suggests that the simulation model would be most effective when employed during an early stage of training, when trainees have the least clinical experience.

Very good, would have been invaluable at earlier stages of training.

There was an overwhelmingly positive response observing the radio-opaque anatomical nature of the model; this was recognized by seven of the participant responses. This also contributed to the real-time feedback, which was seen as a positive outcome.

Excellent XR images, very realistic for finding trajectory etc and visualising spread.

To ascertain constructive criticism and areas for improvement, there were questions about technical issues and problems encountered. There were 17 responses to this question, 3 of which were to indicate no technical issues. The most common reported problem was that the model had been used several times before, and there were wire paths left behind, which were impacting the tactile feedback and allowing the wire to fall into the previous tract.

Model had been used by earlier sessions therefore tracts were present that wires intended to want to fall into and the feel on the distal cortex was often lost.

Other comments with areas for improvement included the overlying lattice structure, making the radiograph appearance of the bone difficult to interpret, particularly when the elbow was bent into the position used for wire placement in the clinical setting. The bone was also reported as harder than the true feel of paediatric bone in response to K-wires. One participant reported the overlying silicone soft tissue sleeve was too mobile, which is particularly relevant as some surgeons would use a skin marker to identify anatomy, which would not be possible with the non-fixed skin mimic.

When asked if they would use this kind of simulation training again, 14 participants agreed that 3D model simulation would have a role in their future training. The participants who justified their responses cited a safe learning environment with the opportunity to acquire skills.

Yes. Great to practice technique in low stakes environment.

The theme of being useful for trainees who have had less exposure to the procedure was apparent, with acknowledgement of the other potential uses of 3D models outside the paediatric supracondylar scenario.

… for learning new procedures or gaining volume in procedures there is not much exposure to. Good for initial stages of training to expose trainees to cases and operations.

Simulation-based education in surgery finds strong theoretical grounding in mastery learning, deliberate practice, and cognitive load theory (CLT). CLT suggests that learning is shaped by the limitations of working memory, with intrinsic load (IL) determined by task complexity and the learner’s expertise [15]. Recent work in simulation-based education underscores how CLT and fidelity shape learning effectiveness. For instance, McLean et al. describe the importance of matching fidelity to learner stage and task complexity to enhance skill transfer by ensuring that both physical realism and user interface demands are appropriate [16].

At present, a common simulation tool is a synthetic ‘Sawbones’ which has a texture and density like bone, but there is no interaction with the soft tissues. In reality, the challenge of surgery is the management of the overlying tissues and visualization of the wire trajectory despite the swollen and deformed envelope. The overlying lattice and skin-mimicking material give the additional advantage of disguising the previous participant’s performance, as earlier wire passes are hidden. Cadaver simulation is the gold standard for technical skills training, but it has significant financial and accessibility barriers. Despite costly challenges, cadaver simulation arguably offers value for money in the range of procedures that can be performed on a single specimen, such as K-wiring, open reduction and, particularly, exploration of the neurovascular anatomy. The 3D printed models provide an anatomically specific simulation alternative, which has been demonstrated to be useful in the training of trauma and orthopaedic registrars with the unique advantage of real-time radiographic assessment. The results demonstrate an overwhelmingly positive response to this style of simulation.

Previous work, by Long et al., has demonstrated the advantages of using a simulated model training for a group of orthopaedic residents in the United States. Comparison of training using a traditional wire navigation simulation training session was made to training using a new simulator model, designed to replicate the look and feel of navigating K-wires through soft tissue and bone, with the generation of a computer-based image mimicking intra-operative fluoroscopy. The outcomes assessed were the number of fluoroscopic images obtained during the residents’ cases performed in theatre and the wire spread at the level of the fracture. The group that had the additional training used significantly fewer fluoroscopic images and completed the procedure significantly quicker, but the wire spread at the level of the fracture was not improved. In summary, the outcomes were unchanged, but the time and radiation required to achieve them were both reduced [8].

Using the advanced 3D printing technologies, the model replicates the anatomical and biomechanical features of a paediatric elbow, resulting in a hands-on experience that closely mirrors real surgical scenarios, helping trainees to develop the surgical confidence to perform the procedure in appropriate clinical settings. Using the image intensifier adds to the realism of the simulation, including the associated requirement for personal protective equipment in the form of lead gowns. Altogether, this contributes to the psychological engagement and immersive experience; this type of multisensory integration simulation allows muscle memory and learned behaviour. The usefulness of training in the cognitive aspects of surgery has been described as a useful adjunct to traditional learning [17].

VR has been a growing area of simulation technology and is emerging in the field of high-acuity, low-occurrence procedures. Work by Groves et al. has shown VR technologies in trauma educational settings may be effective and considered as a cost-effective solution for training to supplement cadaveric-based courses through their work in comparing VR lower leg fasciotomy surgery training model and cadaveric training [16,18,19].

Our study has been designed as a proof-of-concept, aiming to demonstrate the feasibility and potential of the training model and is not able to evaluate all aspects of the use of this model in surgical training. Particularly, this approach can provide valuable insights into the potential of the training model for surgical education, but cannot be used to convincingly draw conclusions about the direct impact of the training method on patient outcomes. Patient outcomes, such as surgical success rates, complication rates and long-term prognosis, are influenced by various factors beyond the training method alone, and it is difficult to draw conclusions on the transfer of simulation skills to real-world performance.

Due to the nature of the model, there was no fracture present to reduce; therefore, the critical skill of closed reduction of supracondylar fractures is not demonstrated in this simulation model. For the senior trainee cohort, this makes the model too simple. A feature of any good simulation model is the ability to cover a range of surgical procedures and scenarios so that trainees can practice and master a diverse set of skills.

There are limitations in the study design, including the absence of a control group, the risk of model fatigue from repeated use and the lack of structures at risk, particularly the neurovascular structures, which limits the model fidelity. We recognize that measures of participant self-confidence can be interpreted variously, but justify their use in this proof-of-concept study alongside the use of more objective measures of technical proficiency.

Finally, this study design is not able to directly evaluate the effectiveness of the training received in terms of improving surgical skills or performance, but instead focuses on validating the model as a tool for education and understanding participants’ experiences and perceptions. Further work could assess the results of repeated assessments for trainees to evaluate if performance improves with this kind of training.

The successful development of 3D printed models for use in surgical training signifies an ongoing transition in the tools and methods used for training surgeons prior to facing the complexities of an operating theatre. By combining realism and low-risk training, trainees self-reported confidence levels can be improved, particularly amongst novice operators.

As a result of this proof-of-concept study, there is an opportunity for further refinement and improvements to be made, and at present, there is a significant financial cost associated with these novel 3D printed models, which may represent a barrier to their widespread use. However, 3D printing remains an exciting and innovative tool for use in training and preparation of trainee surgeons to enhance patient care and improve surgical outcomes.

Catherine Gilmore: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Writing – Original Draft; Richard Napier: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – Review & Editing; Jim Ballard: Conceptualization, Writing – Review & Editing, Supervision

We thank the Trauma and Orthopaedics Research Charity (TORC) for the provision of their funding support and expertise in the analysis of data. TORC charity number NIC105791. We also acknowledge the financial support of Helping Hand charity number NIC102447.

None declared.

None declared.

None declared.

The Association for Simulated Practice in Healthcare (ASPiH) have supported the publication of this work through their fee waiver member benefit.

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.