Simulation scenarios should be designed in a way that addresses the needs and expectations of learners of varied backgrounds and experience levels. Varied degrees of complexity or difficulty in simulation exercises may be an effective means to optimally align learning objectives with outcomes.

This systematic review was conducted according to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses standards. A search of PubMed, Embase and Cochrane was conducted over a period of 2 years up until 30 April 2024. Studies comparing simulation training outcomes using a scenario with two or more different levels of complexity were eligible for inclusion. Studies comparing simulation training using the same scenario with learners in different conditions (e.g. sleep-deprived) were excluded. Risk of bias was assessed using Cochrane Risk of Bias 2 for randomized trials and Risk Of Bias In Non-Randomized Studies of Interventions for observational studies.

In total, 15,348 studies were identified that met criteria for screening, yielding 21 included studies (8 randomized and 13 observational studies). Among study outcomes, 6 randomized and 10 observational studies examined skill; 1 observational study examined knowledge, and 3 randomized and 8 observational studies examined attitudes, stress or confidence. There was significant heterogeneity in study methods, participants, interventions and outcomes of interest; all included studies had at least moderate risk of bias. Evidence for all outcomes was of very low certainty due to inconsistency, imprecision and risk of bias. Fifteen of 21 studies reported at least one outcome for which a significant difference was found between scenario complexity levels.

This systematic review found marked heterogeneity and risk of bias among studies. The findings support the contention that scenario complexity may be a useful component of instructional design in simulation education to enhance outcomes. Future studies should determine how to use differences in scenario complexity to optimize participant engagement and durability of learning objectives.

What this study adds:

•Simulation studies where differing levels of complexity and/or complexity are used can affect learner outcomes

•Varied levels of scenario complexity can effectively distinguish between learners of different experience levels

•The need for better uniformity of reporting interventions and outcomes in simulation research remains significant

One of the recurring necessities in simulation instructional design is the need to create educational experiences that are appropriately contextualized to participants based on their background, level of training and current clinical roles. Such instructional design elements can include characteristics of the simulated patient, environment or both. Additionally, such design elements may be characterized as intrinsic or extrinsic. Intrinsic factors are those that are inherent and unmodifiable in task complexity, such as a more advanced skill requirement or varied background or experience levels of learners. Extrinsic factors are those related to differences in content presentation (e.g.external auditory or visual stimuli, differences in conditions of observation, physical obstacles, etc.). Given that different groups of participants will have different needs, simulation instructors may be called upon to adjust or amend scenarios to most closely align their content with learning objectives that are relevant to groups with differing backgrounds and experience levels.

In 2018, a scientific statement from the American Heart Association summarized the current state of resuscitation education, including important knowledge gaps and research priorities [1]. In a section of this statement dedicated to contextual learning, evidence summaries were presented for maximizing the relevance of education to clinical practice, as well as the role of stress and cognitive load. Simulation scenarios with increased levels of complexity can be construed as an element of instructional design that addresses both of these constructs. Both of these topics were identified as areas in need of further research.

For the present systematic review, we sought to examine whether simulation scenarios administered with varied levels of complexity led to differences in educational outcomes among participants.

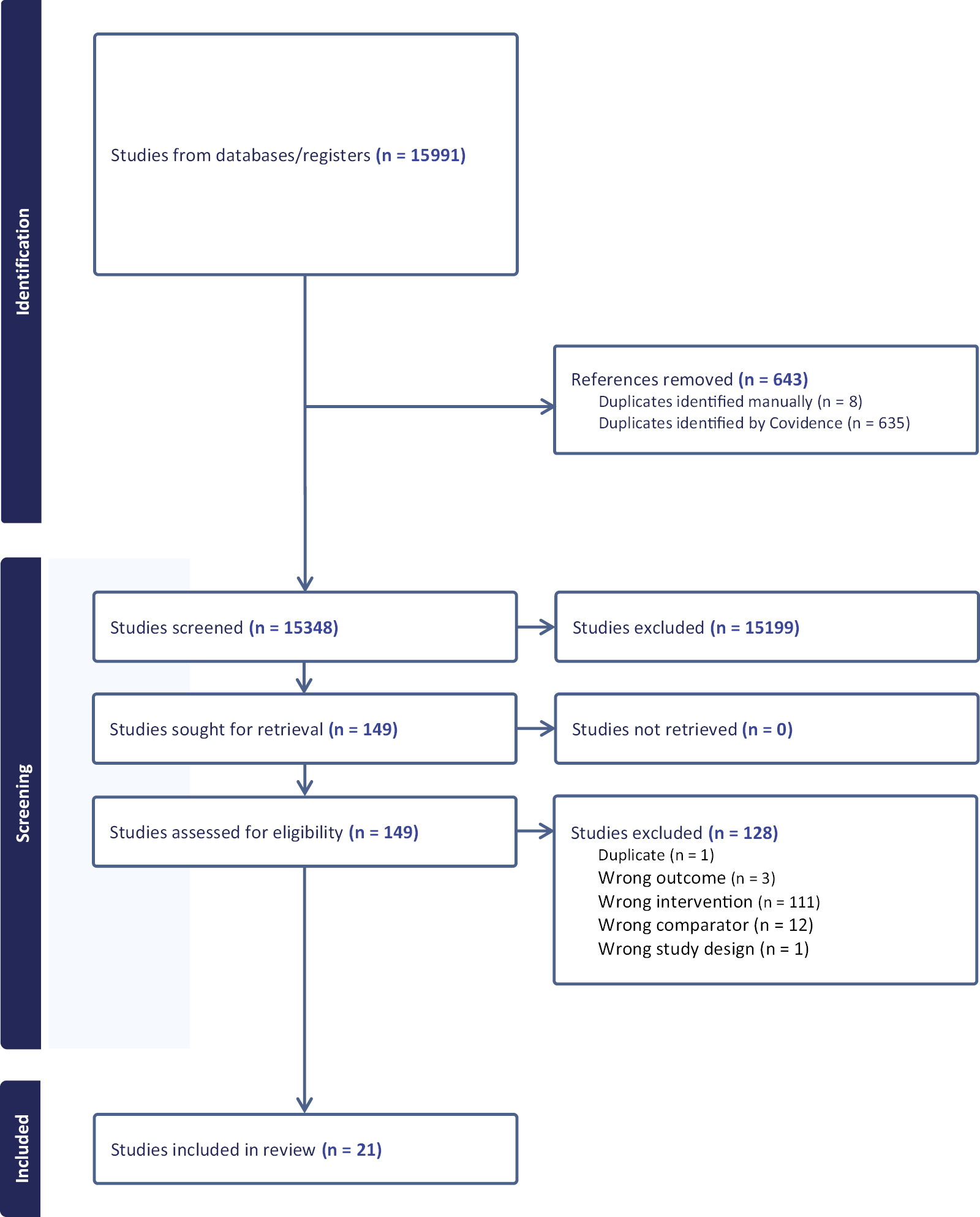

The review was commissioned by the Society for Simulation in Healthcare as part of a global initiative to derive best practice guidelines in relation to the design and delivery of simulation activities. It was planned, conducted and reported in adherence with PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) standards of quality for reporting meta-analyses (see PRISMA diagram, Figure 1) [2]. Because this is a systematic review of published studies, no review board approval was required.

PRISMA diagram.

The review was driven by a research question in the PICO format (Population, Intervention, Control, Outcomes) to formulate the research question[3]:

•Population: healthcare providers, healthcare trainees/students and healthcare teams engaging in simulation training

•Intervention: higher level of scenario complexity

•Control: lower level of complexity

•Outcomes: Bloom’s Taxonomy underpinned three outcomes: skills (improved clinical performance in real and/or simulated settings); knowledge (improved cognitive performance); attitudes (stress, workload, participant satisfaction relating to learning derived from a simulation activity).[4]

Therefore, the research question for this systematic review was ‘what are the effects of varied levels of complexity in simulation scenarios on educational outcomes in healthcare providers’?

We included randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and non-randomized studies (non-RCTs, interrupted time series, controlled before-and-after studies, and cohort studies) as eligible for inclusion. Unpublished studies (e.g. conference abstracts, trial protocols) and grey literature were excluded from consideration.

While the need for varied levels of complexity in experiential medical education has been recognized for a long time, clearly defining complexity in simulation is difficult; a wide variety of phenomena can be included in a scenario to alter the level of challenge to the learner [5]. For the purpose of this systematic review, scenario complexity was considered as elements of instructional design deliberately introduced into a given scenario to increase demands (cognitive and/or psychomotor) on learners. Such increased demands could be attributed to the intended learning outcomes, the modality adopted, the relevance of the activity, the design of the environment and number of interacting elements [6,7]. We anticipated that such modifications of a given simulation exercise would render it more (or less) challenging to participants. No specific criteria were set for what elements of scenario design would be considered eligible; we sought to include as many instructional design elements as possible. Studies that involved changes in complexity in a scenario based on changes in the state of the participant (e.g. capability, sleep deprivation, caffeine consumption, etc.) without changes in the scenario itself were excluded from our analysis.

The search strategy was created with the help of an information specialist with systematic review experience. The original search was completed on 12 January 2024 using EMBASE, Ovid Medline and Cochrane. The search was updated on 14 July 2025, but yielded no additional studies.

The titles and abstracts of all potentially eligible studies were screened for inclusion by pairs of independent reviewers. The full texts of included studies were checked against the inclusion and exclusion criteria independently; any disagreements between the reviewers at either stage were resolved by discussion, finding consensus. Data from each study were independently extracted by a pair of reviewers and grouped separately according to the predefined outcomes (skill, knowledge and attitude/affective responses).

Two reviewers (AD and KS) independently assessed the certainty of evidence of individual studies using the GRADE approach (Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation) [8]. In case of disagreement, consensus was reached by discussion. Risk of bias was assessed by the same two reviewers. The Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool for randomized trials (RoB 2) was used for randomized studies [9]; the Risk of Bias In Non-randomized Studies of Interventions (ROBINS-I) was used for observational studies [10].

Due to the substantial clinical and methodological heterogeneity of the studies identified after the search, no meta-analysis was attempted; therefore, a narrative summary is provided.

The search identified 15,991 articles; after removal of duplicates, 15,348 titles and abstracts were screened. Of these, 15,195 were excluded, leaving 149 full-text articles to be screened for eligibility (Figure 1). In total, 21 studies were identified for inclusion [11–31]. Three RCTs [17,21,23], 5 randomized crossover trials [11,12,15,22,25], and 13 observational studies [13,14,16,18–20,24,26–31] comprised the final set of included studies. Six studies were conducted in the United States [13–16,27,30]; six studies in Canada [11,17,18,21–23]; eight studies in Europe [12,19,20,24–26,28,31] and one in Asia [29]. Nine studies were conducted with physicians [11,18,20,21,25,27,28,30,31]; six were conducted with medical students [13–15,17,24,29]. Two studies involved prehospital providers [12,22] and two involved nursing students [16,26]. The remaining studies involved multiple provider groups [19,23]. There were no included studies with laypeople as subjects.

Study design details are reported in Table 1; there was marked heterogeneity between studies with regard to the study design, the selected interventions to assess the skills, knowledge and affective domains of participants, and the manner in which outcomes were reported.

| Study | Study design | Population and setting | Number of participants | Description of control group | Description of intervention group | Outcome measures (S = skill; K = knowledge; A = affective) | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bensouda, 2018 | Randomized crossover trial | Junior doctors, Canada | 25 per group (50 total) | Simulated neonatal intubation with single observer (condition A) | Audience of 5 observers (condition B) | S (time to intubation) | Time to intubation: Condition A: 31 s (28–34 s); Condition B: 35 s (32–38 s); p = 0.07 |

| Bjorshol, 2017 | Randomized crossover trial | Paramedic teams, Norway | 19 teams | Simulated field setting, no additional people present | Distracting bystander (non-native language speaking, ongoing added comments to increase pressure) | S (CPR quality, time to critical interventions); A (self-reported workload (NASA TLX)) | CPR quality: no significant difference; Time to defibrillation: shorter in intervention group (121 s vs. 209 s; p < 0.001); NASA TLX: increase in scores for mental demands, time pressure, frustration, and effort |

| DeMaria, 2016 | Observational study | Medical students, USA | 26 (13 per group) | ACLS scenario with patient survival | ACLS scenario with patient death | S (clinical performance in ACLS scenario at 6 months); K (ACLS written test at 6 months); A (impact of event scale at 6 months) | Skill: Clinical: no difference (75 vs. 83%; p = 0.18); Knowledge: no difference (80 vs.78%; p = 0.89); Impact of Event Score: no difference |

| Evans, 2017 | Observational study | 4th year medical students, USA | 16 | Suturing of cadaver laceration undisturbed | Suturing cadaver laceration with mock page during procedure | S (time suturing; GRS score (rating instrument for suturing performance)) | Total time suturing with page: 104 s (vs. 90 s); p < 0.01 GRS score 16.4 with page (vs. 15.6) |

| Gil, 2020 | Randomized crossover trial | Medical students, USA | 31 (16 nonpreferred music first, 15 preferred first) | Preferred genre of music playing | Least preferred genre of music playing | S (score on DaVinci simulator during tasks) | Higher scores with preferred music (77.4 vs. 72.2, p = 0.025) |

| Guhde, 2011 | Observational study | Third year nursing students, USA | 134 | Simple adult medical scenario (single problem) | Complex scenario | A (survey on thinking, assessment, and satisfaction | No significant differences in mean Likert scale scores |

| Haji, 2016 | RCT | Medical students, Canada | 38 (19 per group) | Simple scenario during skill acquisition (followed by very complex scenario during transfer phase) | Complex scenario during skill acquisition (followed by very complex scenario during transfer phase) | S (global rating scale for LP performance); S (GRS for communication skills during transfer phase); S (# of LP attempts); S (# of sterility breaches); S (cognitive load; reaction time difference and signal detection rate to secondary stimulus) | Skill acquisition phase: simple group GRS LP scores higher than complex group (p = 0.002); fewer needle passes (0.002); fewer sterility breaches (p < 0.001). Reaction time and cognitive load declined in simple but not complex (p < 0.01). Transfer phase: no diff in LP performance or needle passes; fewer sterility breaches in simple group (p = 0.02); GRS worse from retention to transfer in simple group(p = 0.001) (no diff in complex); no diff in cog load measures |

| Harvey, 2012 | Observational study | Emergency Medicine and surgical residents (both doctors), Canada | 13 | Low stress trauma simulation | High stress trauma simulation (distractors included, less VS stability) | S (checklist; global rating forms for clinical performance; completion of H&P form); S (ANTS scale); A (measures of stress; STAI; cognitive appraisal) | Checklist: HS 43%; LS 48% (p < 0.05); GRS: HS 59%, LS 61% (NS); ANTS HS 67%, LS 70% (NS); Hx form HS 60%, LS 69% (p < 0.05); STAI scores: End of scenario HS 39.8 LS 31.4 (p < 0.05); 30 min after scneario HS 35 LS 29 (p < 0.05); no diff in HR; change in cortisol: HS +1.56 nm/L vs. LS-1 (p < 0.05) |

| Hughes, 2022 | Observational study | Surgeons and medical students, UK | 10 students, 10 surgeons | Laparoscopy trainer peg threading task (baseline) | Same task with visual overlay; same task with audio distraction | S (time to task completion, distance of instrument motion, instrument smoothness); A (self-reported pressure/distraction) | Time: No change in time to completion for either distraction in either group; Smoothness: No diff in instrument smoothness in students, 37% decrease in smoothness in surgeons with audio (p = 0.05); Distance: no differences; Self-report: no differences |

| Kryillos, 2017 | RCT | Medical specialty doctors, Quebec. | 26 (13 residents, 13 attendings) | Simulated surgical tasks (without music) | Same surgical tasks with music playing | S (anti-tremor parameters, Capsulorhexis task) | No significant differences |

| Kyaw Tun, 2012 | Observational study | Junior doctors, UK | 10 experts, 10 novices | Laceration scenario (easy) | Same scenario with difficult patient | S (laceration repair rated by validated instruments (OSATS-TSC [10 pt], OSATS-GRS [5 pt] and DOPS [6 pt]) | Simple scenario: no differences in any instrument. Complex scenario: experts better than novices (OSATS-TSC: 1 point (95% CI 0–6 pts); OSATS-GRS (1 pt, 95% CI 0.4–1.9); DOPS: 1.2 pt (0.3–2.2) |

| Leblanc, 2012 | Randomized crossover trial | Paramedics, Canada | 22 | Low stress resuscitation scenario | High stress resuscitation scenario | S: global clinical score A: self-reported anxiety |

S: clinical score worse in high stress scenario (14/21 vs. 12/21, p < 0.05) A: increased in high stress case (p<0.05) |

| Lizotte, 2017 | RCT | Medical students and Senior doctors, Canada | 42 | Low stress neonatal resuscitation (cardiac arrest with ROSC) | High stress neonatal resuscitation (cardiac arrest with nonsurvival) | S: global score (NRP megacode) A: self-reported stress |

No significant differences |

| Macdougall, 2013 | Observational study | Medical students, UK | 40 | High realism simulation stations designed to generate increased stress | NA | A (self-reported knowledge and confidence) | No significant differences pre- and post-sessions |

| Marjanovic, 2018 | Randomized crossover trial | Medical specialty Doctors, France | 26 | Intubation scenario | Same scenario with limited physical space and patient deterioration | S (intubation success); A (NASA TLX, self-reported stress) | S: 96% success in basic vs. 15% in difficult scenario A: reported stress and NASA TLX higher in stress scenario (p < 0.001) |

| Martin-Conty, 2020 | Observational study | Nursing students, Spain | 59 | CPR in normal temperature | CPR in Hot (+40c) and Cold (-35c) conditions | S (CPR efficacy) | No significant difference |

| Matern, 2018 | Observational study | Junior doctors, USA | 125 | Patient handover | Patient handover with either a looped recording of hospital noise, or looped recorded hospital noise with standardized pages going off | S (efficacy of patient handover) | The Control group showed the same level of prioritisation as the loop + pager group. They gave the least amount of opportunities to ask questions and had no issues being heard during handover (p ≤ 0.001) |

| Muhammad, 2019 | Observational study | Consultant Neurosurgeons, Finland | 2 | Simulated vessel wall suturing procedure | Same simulated procedure with OR noise or meditation music | S (efficacy of suturing) | The number of repeated movement, which did not achieve the intended goal reduced in both surgeons when meditation music was played (p ≤ 0.05). |

| Poolton, 2011 | Observational study | 4th and 5th Medical students, Hong Kong. | 30 | Pegboard laparoscopy trainer | Pegboard laparoscopy trainer under time constraints (try to perform the task more quickly than their best time during the training phase) | A (self-reported stress) | Time pressure was considered to be significantly more stressful than control (p < 0.001) |

| Redmond, 2020 | Observational study | Emergency Medicine Residents (doctors), USA | 12 | Neonatal resuscitations; 3 increasing levels of difficulty | NA | A (self-reported stress) | HR data: Low freq/hi freq ratio lowest in scenario 1 than scenario 2 (2.3 vs. 4.7, p = 0.04) and scenario 3 (2.3 vs. 4.6, p = 0.04); self-reported stress increased through 3 scenarios |

| Weigl, 2016 | Observational study | Surgical specialty doctors, Germany | 19 | Vertebroplasty simulation | Vertebroplasty simulation with disruption | S (trocar position, # of X-rays); A (SURG-TLX score) | A: SURGTLX scores higher in difficult scenario (37 vs. 31, p < 0.01); association btw higher SURGTLX and poorer accuracy with trocar (p = 0.04); S: no differences |

ACLS: Advanced Cardiac Life Support; ANTS: Anaesthesia Nontechnical Skills; CPR: cardiopulmonary resuscitation; DOPS: Direct Observation of Procedural Skills; GRS: global rating scale; LP: lumbar puncture; NA: not applicable; NASA TLX: NASA Task Load Index; NRP: Neonatal Resuscitation Program; OSATS-TSC: Modified Objective Structured Assessment of Technical Skills–Task Specific Checklist; OSATS-GRS: Objective Structured Assessment of Technical Skills – Global Rating Score; STAI: State-Trait Anxiety Inventory; SURGTLX: Surgery Task Load Index.

The risk-of-bias assessments (categorized as low, some concerns and serious) are summarized in Table 2. All included studies were determined to have at least a moderate risk of bias. The main issues, related to bias, identified with the studies related to inadequate blinding of participants and assessors, inadequate randomization, incomplete outcome reporting and unclear selection processes (both of participants and the relevance of the simulation for participants). The certainty of evidence was judged to be low for indicators of stress (downgraded for inconsistency and risk of bias) and very low for all other outcomes (downgraded for very serious risk of bias and inconsistency).

| Randomized controlled trials (RoB 2) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author, year | Allocation generation | Allocation concealment | Blinding participants | Blinding assessors | Outcome complete | Outcome selective | Other | Overall | |||||

| Bensouda, 2018 | Some concerns | Low | Low | Some concerns | Low | Low | Low | Some concerns | |||||

| Bjorshol, 2017 | Some concerns | Low | Low | Some concerns | Low | Low | Some concerns | Some concerns | |||||

| Gil, 2020 | Some concerns | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Some concerns | |||||

| Haji, 2016 | Some concerns | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Some concerns | |||||

| Kyrillos, 2017 | Low | Low | Low | Some concerns | Some concerns | Low | Some concerns | Some concerns | |||||

| Lizotte, 2017 | Low | Low | Some concerns | Some concerns | Some concerns | Some concerns | Low | Serious | |||||

| Marjanovic, 2018 | Some concerns | Some concerns | Low | Some concerns | Some concerns | Low | Some concerns | Serious | |||||

| Martin-Conty, 2020 | Low | Some concerns | Some concerns | Some concerns | Low | Low | Low | Some concerns | |||||

| Observational studies (ROBINS-I) | |||||||||||||

| Author, year | Eligibility criteria | Exposure/outcome | Confounding | Follow-up | Overall | ||||||||

| DeMaria, 2016 | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | ||||||||

| Evans, 2017 | Moderate | Moderate | High | Low | Serious | ||||||||

| Harvey, 2012 | Low | Moderate | High | Low | Serious | ||||||||

| Hughes, 2022 | Moderate | Low | Moderate | Low | Moderate | ||||||||

| Kyaw Tun, 2012 | Low | Moderate | High | Low | Serious | ||||||||

| LeBlanc, 2012 | Low | Low | Moderate | Low | Moderate | ||||||||

| Macdougall, 2013 | Low | Low | Moderate | Low | Moderate | ||||||||

| Matern, 2018 | Low | Low | Moderate | Low | Moderate | ||||||||

| Muhammed, 2019 | High | High | High | High | Serious | ||||||||

| Poolton, 2011 | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Serious | ||||||||

| Redmond, 2020 | High | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Serious | ||||||||

| Wiegl, 2016 | Low | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Serious | ||||||||

Two RCTs (40 subjects in control groups and 40 in intervention groups) and four randomized crossover studies (126 subjects) examined clinical skill performance [11,12,15,17,21,23]. Nine observational studies, totaling 407 subjects, examined skill performance [13,14,18,20,22,26–28,31]. Differences in scenario complexity were experimentally achieved by varied methods (e.g. more complex or unstable condition of simulated patient (SP); presence of external sources of distraction, presence of music, simulation ending with death of patient versus survival).

Three studies examined the effect that a stress reaction had on the time to task performance (neonatal intubation and cardiopulmonary resuscitation in adults and neonates) [11,6,17]. One study looked at simulated neonatal intubation performance between two groups; one group’s subjects performed with one observer present, and the other with five observers present. No difference was found in time to intubate between the two groups with different numbers of observers [11].

A second study looked at chest compression quality and time to defibrillation by paramedics during simulated cardiac arrest, with one group performing with an actor present portraying a distressed bystander (experimental) and the other without that bystander (control) [12]. There was a slight increase in the rate of chest compressions under experimental conditions and a longer time to defibrillation under controlled conditions. The NASA Task Load Index (TLX) was used to measure perceived workload and performance demand during scenarios. The NASA TLX reported a significant increase in perceived workload and frustration during the experimental conditions scenario (which was deemed by paramedics to be more realistic).

A third randomized trial looked at simulated neonatal resuscitation and compared performance between a group where the manikin ‘survived’ and one where the manikin ‘did not survive’ [23]. No significant difference in resuscitation performance was found. Three salivary cortisol samples were obtained from each participant (baseline, pre-simulation and immediately after their first simulation) to determine the effect of stress on performance; no difference was found between groups.

One study compared junior and senior physicians performing a simulated suturing of a wound under two sets of conditions: one with a quiet patient and one with a non-compliant patient (who had consumed alcohol) [20]. No difference in performance was found in the simple scenario, but senior physicians had better performance during the non-compliant patient scenario.

The effect that extrinsic factors such as task complexity, auditory stimuli and timed interruptions had on task performance was a recurring theme in eight publications [8,9,17,12,31,21,22,25].

In one study, task complexity was explored to determine the effect this had on medical students’ ability to undertake a simulated lumbar puncture on a young, healthy patient (simple scenario) and on an obese, elderly patient (complex scenario) to the expected standard [11]. The complex scenario elicited a worse performance in participants.

Two studies found improved overall performance in simulated surgical tasks when music was played [15,21]; the first study found the improvement was significant when the music was of the preferred genre of the subject.[15] The second study compared the performance of consultants (n = 13) and senior doctors working in ophthalmology (n = 13) to undertake four simulation scenarios. No statistically significant results were reported in all four scenarios between groups; this included the effect of music on performance.

Seven observational studies examined the effect that auditory stimuli had on performance. The first study examined the effect that having to undertake a cognitive task (answering a pager) whilst performing a simulated wound suturing (a technical task) [8]. In total, 16 fourth-year medical students participated in this study. Each medical student undertook two practice wound suturing under controlled conditions over a 2-week period (a baseline on day 1 and a control the day before the cognitive task). The authors reported a 12% increase in the time taken to complete the simulated wound suturing when the cognitive task was introduced. Two studies found worse overall performance in resuscitation scenarios with distraction (an overwhelmed colleague, increased environmental noise, volume of monitors and alarms, constant two-way radio communication noise and a distressed relative) [18,22]. The fourth study found increased perceived cognitive load during a simulated vertebroplasty procedure when participants (19 junior surgeons with no experience of undertaking the procedure) had to respond to either a telephone call or that the patient was sensing pain during the simulated procedure [31]. The fifth study reported decreased clarity of communication skills during a patient handoff where there was increased environmental noise and participants were being paged [27]. The sixth study found that simulated vessel repair simulation was improved with meditative music playing (although this was with a cohort of two participants) [28]. The final study found no difference in simulated cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) quality among groups performing at different ambient temperatures (cold, ambient and hot), although subjective measurements of stress and anxiety were greatest in the hot environment [26].

An observational study of 26 medical students compared performance on an Advanced Cardiac Life Support (ACLS) written examination 6 months after simulation training [13]. Participants had no previous knowledge of the ACLS course. Following successful completion of this course, they were then allocated to a simulation scenario where the SP ‘survived’ or ‘died’. No significant difference was noted in examination scores between groups.

Three randomized crossover studies (83 subjects) [12,17,25] and seven observational studies (642 subjects) [13,16,19,24,29–31] reported on differences in stress and/or workload based on scenario complexity. Among the randomized studies, two studies of specific procedures (lumbar puncture and intubation of a difficult airway) found that increased complexity led to greater self-reported stress among subjects [17,25]; another study found that resuscitation scenarios with external distraction led to greater workload as measured by a validated instrument (NASA-TLX) [12]. Among the observational studies, five studies reported no difference in self-reported stress between groups [13,16,19,24,31]; two studies found increased stress with more difficult scenarios [29,30].

In this systematic review, we identified a group of studies where a simulation scenario is administered in at least two different fashions, where one of the scenarios is altered to increase the degree of complication, distraction, physical challenge or emotional context. Our goal was to identify differing degrees of complexity in scenarios; amongst our included studies, the ‘intervention’ of interest was markedly heterogeneous, and which of the instructional design changes truly resulted in increased ‘complexity may be difficult to infer. Nonetheless, many of the studies were able to demonstrate the ability to demonstrate distinct outcomes between the experimental groups based on the scenario change(s). Thus, although no specific definition for complexity is available in current literature, being able to challenge learners in a contextually appropriate way is an essential component of scenario design [5].

The overall quality of methodological rigour, including the selection of instruments to measure performance, reported in this systematic review, varied greatly. Therefore, it is not possible to make substantive statements that varying the level of complexity of simulation scenarios has a measurable effect on skill performance and the stress response of participants. Given the significant heterogeneity of the studies, it is not possible to precisely determine what combination of instructional design elements contributes to scenario complexity the most, nor is it possible to extrapolate the impact of such changes on clinical performance and/or patient care delivery in typical practice. Despite this limitation, the evidence suggests that instructors can create a higher level of complexity by using design elements seen among these studies.

There is a recurring tension in this body of literature where the validity of a simulation scenario from the perspective of the participant is not always apparent or reported. There are frequent instances where participants have no experience of undertaking a skill or procedure prior to the simulation scenario. Therefore, the stores of prior knowledge that participants can apply within this scenario are limited, and this can compromise their perceived agency and their ability to perform to the expected standard.

The majority of simulation scenarios were designed by those who are considered experts. The role of an expert is not well defined in the literature (only one article does this) [17]. The process for determining a relevant stimulus for each scenario (task complexity, auditory stimuli, visual stimuli, environmental conditions, perceived stressors, etc.) was a subjective process made by ‘experts’ in relation to their area of practice. Very few studies used literature or available data to determine the most appropriate stimulus for a scenario. It was noted that authors would share the outcomes from their simulation scenario, but the context for the data collection (the simulation itself) was described in little or no detail. It was noted that only three articles described the preparation of participants (prior to attending the simulation and immediately before this activity) and interventions to promote the well-being of participants during the simulation [12,14,16]. This does create an inherent challenge for healthcare individuals or teams who experience similar challenges and wish to replicate these experimental conditions, as the exact content of this simulation has not been declared.

While not a specific outcome of interest for the present review, several of the included studies reported changes in measurable physiologic parameters (e.g. heart rate, blood pressure, salivary cortisol or dihydroepiandosterone [DHEA] levels) as a proxy measure of stress. Bensouda et al.and DeMaria et al. both found a significantly greater increase in heart rate in the more difficult scenarios in their trials [11,13]. Harvey et al. and LeBlanc et al. demonstrated significantly greater salivary cortisol levels with more difficult scenarios [18,22]; DeMaria et al. found no difference in cortisol or DHEA level between groups [13]. Similar to the earlier discussion about the relationship between scenario complexity and educational impact, the relationship between physiologic stress and improved educational effectiveness remains elusive. Given the growing number of studies using these indices to quantify physiologic changes, future research should take advantage of these reproducible outcomes as the links between stress and learning are explored further.

In 2018, a task force assembled by the American Heart Association released a Scientific Statement on resuscitation educational science [1]. In that statement, evidence on cognitive load and stress on participants in the context of resuscitation education was presented, but no specific recommendations could be made based on the limited data and mixed reported findings of published studies. The results of our review are more consistent (albeit not uniform) in demonstrating that increased complexity of scenarios has a measurable impact on performance. Redmond et al., in a report on measured stress in neonatal resuscitation scenarios, stated that ‘Stress can be a tool, or stress can be a toxin’ [30]. It is intuitive that any given participant will have her/his own ‘sweet spot’ where a certain amount of challenge in a scenario enhances engagement and learning outcomes without being too stressful or taxing to negatively impact psychological safety; how to best determine that in a participant remains elusive. Several recent studies in both nursing and physician trainees have yielded preliminary evidence about the overlap and/or contrast between stress and learning outcomes, using both quantitative and qualitative methods [30,32,33]; further investigation is needed on how to determine and adapt curriculum design to capitalize on these factors.

Several limitations to the findings of this review should be acknowledged. As described earlier, the studies included in this review demonstrated marked heterogeneity, making summative conclusions about the impact of scenario complexity on educational outcomes nearly impossible. As is frequently the case in educational research, outcomes in the form of global assessment of skill were done using an array of instruments, some but not all of which have been determined to be psychometrically robust, biasing the overall results by worsening inconsistency. The development of broadly reproducible and applicable assessment tools in future studies is highly recommended to enable comparative studies and meta-analysis. This recommendation is aligned with the work of Sevdalis et al., who advocated the adoption of validated reporting frameworks, such as the STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology and the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials, to create a consistent reporting structure, which would address the noted poor reporting of simulation-based publications. At the time, this authorship group was the editor of the three largest simulation journals in the world: (1) Sevdalis: British Medical Journal for Simulation and Technology Enhanced Learning (BMJSTEL), (2) Nestel: Advances in Simulation (AiS) and (3) Gaba: Journal of Simulation in Healthcare (JiSH). This authorship group endorsed the utilization of these frameworks to improve the rigorous reporting of scientific publications and to enhance the current level of influence and impact that the simulation community has within healthcare education [34]. This systematic review has demonstrated the frequent use of randomized trials within the simulation community. The increase in utilization of controlled and experimental conditions is encouraging, as this has the potential to influence the quality of data captured and the reliability of the outcomes reported. In the majority of randomized trials, there was no significant difference reported between the control and the intervention groups. Constructive debate within the simulation community is required to determine whether this methodological approach is ‘a good fit’ for simulation-based research activities or whether other approaches are more appropriate (such as qualitative methodologies and mixed methods research) to enhance the influence that this community has within healthcare education.

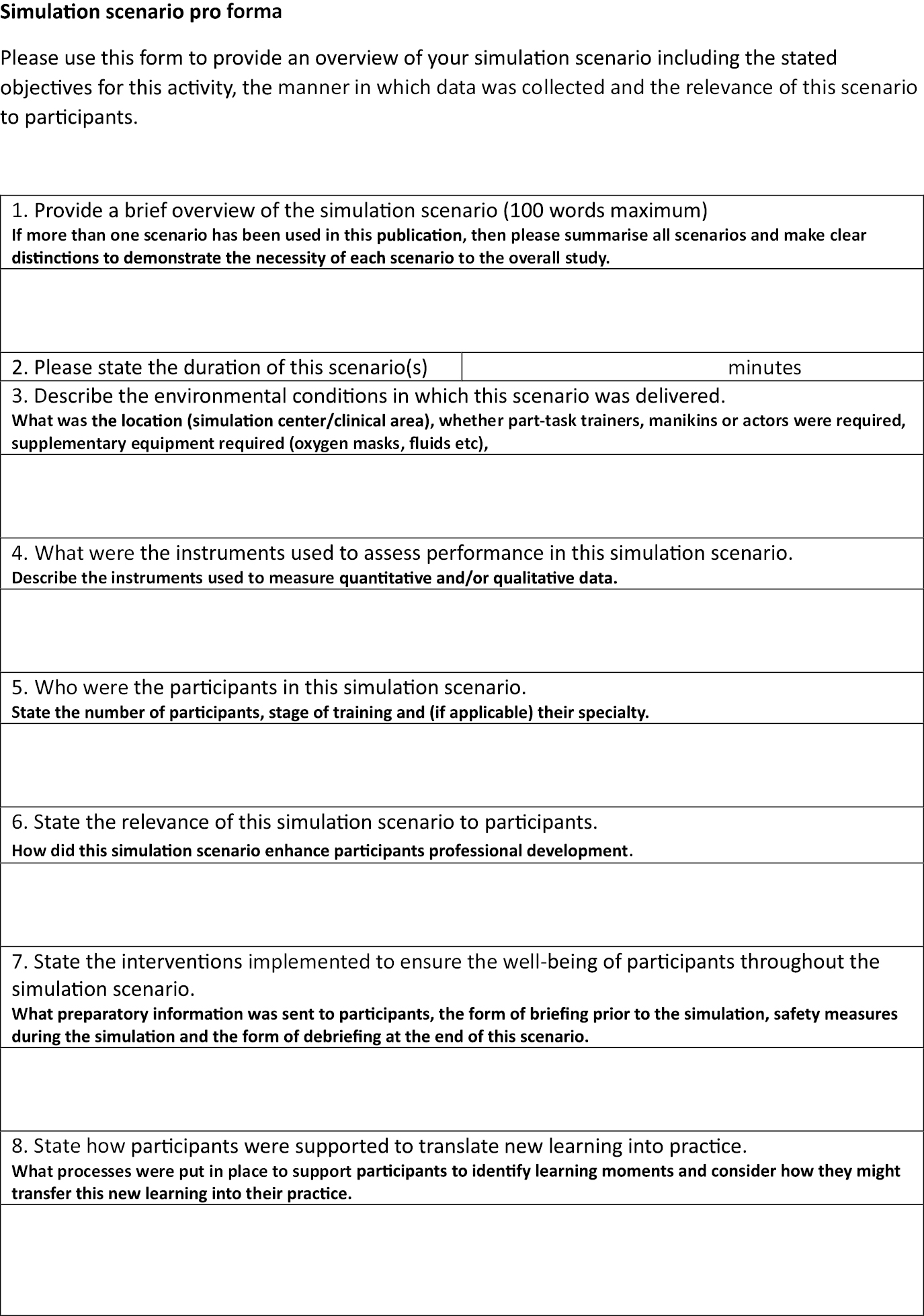

Based on the noted significant heterogeneity of the studies in terms of intervention, assessment(s) and outcomes, this review recommends the development of processes that increase the standardization of reporting the outcomes of simulation scenarios within the literature. To enhance the standardized reporting of simulation scenarios within the literature, it is recommended that journal editors consider requesting the inclusion of a description of the simulation scenario as an appendix for each manuscript. This appendix could be a pro forma that journal editors could endorse and would include a brief overview of the scenario. If two scenarios are included in a research study (in this systematic review, control and intervention scenarios were used frequently), then an overview of both scenarios should be included, and clear distinctions made between both scenarios. The duration of the scenario should be stated along with the interventions taken to ensure the well-being of participants throughout the simulation. This systematic review noted an increased use of validated assessment tools such as OSATS, DOPS and Mini-CEX to objectively measure performance demand. The NASA-TLX and the State Trait Anxiety Inventory and Trait Anxiety questionnaires were utilized to subjectively measure performance demand [35]. To improve the standardized reporting of simulation-based research, it is recommended that the objectives and the measurement instrument be stated in this pro forma to allow other simulationists to recreate these conditions and to capture comparable data. The rationale for selecting participants and the relevance of the scenario to this population should be stated (in this systematic review, it was not always apparent why a certain population had been recruited). Finally, a statement regarding how participants were supported to translate new learning into practice should conclude this pro forma document (Figure 2). This appendix would ensure a more standardized approach to the reporting of simulation scenarios, which has potential benefits of increasing the sharing of best practices and the generalizability of simulation-based research in an organic manner within the global simulation community.

Simulation scenario pro forma.

Almost all of the included studies reported outcomes of individual subjects as a reaction to a training exercise, with a few studies reporting on changes in performance based on knowledge or skill acquisition. This observation is aligned with the seminal publication by Issenberg et al in 2005 and is something the global simulation community needs to address [36]. The simulation scenario pro forma described in the discussion might be helpful in addressing these issues. In addition, the results of this review highlight several important knowledge gaps. All of the included studies were performed at single institutions; only one enrolled subject with varied backgrounds in health care. None of the studies included in the review examined the time requirement or cost of implementing the interventions used to adjust scenario complexity or complexity, nor did any of them examine how best to train instructors to appropriately conduct and/or adjust scenarios to maximize the positive impact of scenario complexity. None of the studies included input from participants in the design of the simulation scenarios or the interventions, which might elicit an increased demand during this activity; the role of co-creation (where participants and experts develop scenarios together) as a means of determining beneficial scenario complexity, which correlates with participants’ stage of training and lived experience, requires further research [28]. The interplay of these factors requires further research to better delineate how simulation curricula can accommodate participants with diverse learning styles and levels of capability in a beneficial and developmental manner.

This systematic review supports the contention that scenario complexity may be a useful component of instructional design in simulation education to enhance outcomes. Future studies should determine how to use differences in scenario complexity to optimize participant engagement and durability of learning objectives. Future research should also clarify the ideal use of stress measurement (physiologic and/or psychologic) to guide curriculum design using scenario complexity.

The authors would like to thank Danielle Gerberi (information specialist) for her help with this review. We would also like to thank the leadership team from the Society for Simulation in Healthcare (Dimitrios Stefanidis, Sharon Decker, Sharon Muret-Wagstaff, David Cook, Mohammad Kalantar, Mohammed Ansari, Kathryn Adams, and Kristyn Gadlage) for their support and guidance in this process. The Association for Simulated Practice in Healthcare (ASPiH) have supported the publication of this work through their fee waiver member benefit.

None declared.

No authors have any significant financial conflicts of interest to disclose.

None declared.

None declared.

None declared

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

30.

31.

32.

33.

34.

35.

36.

Embase via Ovid (1974+):

| # | Query | Results |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | exp simulation training/ or exp simulation/ or exp simulator/ or cadaver/ or exp anatomic model/ or exp resuscitation/ | 563,698 |

| 2 | (biosimulat* or simulat* or telesimulat* or haptic* or vignette* or mechanical-patient* or positioning-doll* or bench-train* or bench-model* or task-trainer* or training-box or cadaver* or (anatom* adj1 model*) or surgical-model* or moulage* or manikin* or mannikin* or mannequin* or harvey or sim-man or mistvr or (mist adj1 vr) or vitalsim or simsurgery or laerdal or mock-code* or crisis-resource-management or crisis-event-management or crew-resource-management or knot-tying or sutur* or team-training or ((clinical or physical or patient) adj1 exam*) or ((procedur* or skill* or experiential or psychomotor or motor-skill* or dexterity) adj1 (lab or laboratory or training or practice or practise or perform*)) or (skill* adj1 acqui*) or skills-course or skills-curricul* or technical-skill* or ((procedur* or surg* or operati*) adj1 (skill* or teach* or technique*)) or case-scenario* or practical-course or (practical adj1 training) or resuscitat* or life-support or ACLS or BLS or PALS or CPR or chest-compression* or arrest or defibrillat* or cardiopulmonary-rescue).ab,kf,ti,dq. | 1,580,307 |

| 3 | 1 or 2 | 1,735,871 |

| 4 | exp learning/ or continuing education/ or curriculum/ or educational technology/ or in service training/ or interdisciplinary education/ or interprofessional education/ or exp medical education/ or “outcome of education”/ or problem based learning/ or exp teaching/ or virtual learning environment/ or exp health student/ or exp paramedical education/ or teaching/ or clinical competence/ or nursing competence/ or professional competence/ or ed.fs. | 1,094,503 |

| 5 | 3 and 4 | 99,404 |

| 6 | (evaluat* or assess* or compar* or impact* or effect* or validat* or improv* or measure* or reliab* or outcome* or random* or control* or pretest* or pre-test or pre-post or chang* or cohort* or success-rate* or scor* or questionnaire*).ab,hw,kf,ti. | 25,622,930 |

| 7 | 5 and 6 | 85,249 |

| 8 | limit 7 to conference abstract | 23,795 |

| 9 | 7 not 8 | 61,454 |

| 10 | limit 9 to yr=“2000 -Current” | 56,335 |

| 11 | case report/ or case-report*.pt,ti. | 2,726,367 |

| 12 | exp clinical trial protocol/ | 1,579 |

| 13 | ((trial adj2 protocol) or technical-report).pt,ti. | 2,940 |

| 14 | or/11-13 | 2,730,451 |

| 15 | 10 not 14 | 55,436 |

| 16 | mental stress/ or critical incident stress/ or anxiety/ or exp cognition/ | 2,778,618 |

| 17 | (context* or ((mental or psych* or level*) adj1 stress*) or anxi* or cognitive or thinking or complex* or difficult* or realism or realistic* or intrica* or authentic* or true-to-life or life-like or lifelike or real-world or ((knowledge or skill*) adj2 (requir* or level*)) or design* or uncertain* or metacognit* or comprehension or intuit* or macrocognit* or information-overload or information-load or working-memor* or mental-load).ab,kf,ti,dq. | 6,747,926 |

| 18 | or/16-17 | 8,345,474 |

| 19 | 15 and 18 | 43,475 |

| 20 | exp comparative study/ or (compar* or versus or vs or contrast*).ab,kf,ti. | 10,424,619 |

| 21 | 19 and 20 | 16,221 |

| 22 | limit 21 to yr=“2011 -Current” | 12,243 |

| 23 | exp simulation training/ or exp surgical technique/ or (simulat* or learn* or educat* or train* or teach* or competenc* or skill* or procedur* or surg* or operat* or resuscitat* or life-support or ACLS or BLS or PALS or CPR or chest-compression* or arrest or defibrillat* or cardiopulmonary-rescue).ti,kf. | 3,595,888 |

| 24 | 22 and 23 | 9,996 |

MEDLINE via Ovid (1946+ and Epub Ahead of Print, In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations and Ovid MEDLINE(R) Daily):

| # | Query | Results |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | exp Simulation Training/ or exp computer simulation/ or Cadaver/ or exp Models, Anatomic/ or Crew Resource Management, Healthcare/ or exp Resuscitation/ed or exp Life Support Care/ed | 352,726 |

| 2 | (biosimulat* or simulat* or telesimulat* or haptic* or vignette* or mechanical-patient* or positioning-doll* or bench-train* or bench-model* or task-trainer* or training-box or cadaver* or (anatom* adj1 model*) or surgical-model* or moulage* or manikin* or mannikin* or mannequin* or harvey or sim-man or mistvr or (mist adj1 vr) or vitalsim or simsurgery or laerdal or mock-code* or crisis-resource-management or crisis-event-management or crew-resource-management or knot-tying or sutur* or team-training or ((clinical or physical or patient) adj1 exam*) or ((procedur* or skill* or experiential or psychomotor or motor-skill* or dexterity) adj1 (lab or laboratory or training or practice or practise or perform*)) or (skill* adj1 acqui*) or skills-course or skills-curricul* or technical-skill* or ((procedur* or surg* or operati*) adj1 (skill* or teach* or technique*)) or case-scenario* or practical-course or (practical adj1 training) or resuscitat* or life-support or ACLS or BLS or PALS or CPR or chest-compression* or arrest or defibrillat* or cardiopulmonary-rescue).ab,kf,ti. | 1,270,985 |

| 3 | 1 or 2 | 1,441,577 |

| 4 | exp Learning/ or exp curriculum/ or exp Educational Measurement/ or exp inservice training/ or exp teaching/ or exp Education, Professional/ or exp Students, Health Occupations/ or exp Schools, Health Occupations/ or exp Faculty/ or ed.fs. or exp Health Occupations/ed or exp Patient Care Team/ | 1,065,715 |

| 5 | 3 and 4 | 72,360 |

| 6 | exp Educational Measurement/ | 159,969 |

| 7 | (evaluat* or assess* or compar* or impact* or effect* or validat* or improv* or measure* or reliab* or outcome* or random* or control* or pretest* or pre-test or pre-post or chang* or cohort* or success-rate* or scor* or questionnaire*).ab,hw,kf,ti. | 19,708,693 |

| 8 | 6 or 7 | 19,748,812 |

| 9 | 5 and 8 | 62,212 |

| 10 | limit 9 to yr=“2000 -Current” | 54,452 |

| 11 | case reports/ or case-report*.pt,ti. | 2,294,973 |

| 12 | clinical trial protocol/ or (trial adj2 protocol).pt,ti. | 8,607 |

| 13 | technical report/ or technical-report.pt,ti. | 3,941 |

| 14 | or/11-13 | 2,307,060 |

| 15 | 10 not 14 | 53,901 |

| 16 | Stress, Psychological/ or anxiety/ or exp Cognition/ | 385,796 |

| 17 | (context* or ((mental or psych* or level*) adj1 stress*) or anxi* or cognitive or thinking or complex* or difficult* or realism or realistic* or intrica* or authentic* or true-to-life or life-like or lifelike or real-world or ((knowledge or skill*) adj2 (requir* or level*)) or design* or uncertain* or metacognit* or comprehension or intuit* or macrocognit* or information-overload or information-load or working-memor* or mental-load).ab,kf,ti. | 5,416,071 |

| 18 | or/16-17 | 5,568,091 |

| 19 | 15 and 18 | 27,256 |

| 20 | Comparative study/ or Comparative Effectiveness Research/ or (compar* or versus or vs or contrast*).ab,kf,ti. | 8,197,734 |

| 21 | 19 and 20 | 10,923 |

| 22 | limit 21 to yr=“2011 -Current” | 7,870 |

| 23 | exp Simulation Training/ or (simulat* or learn* or educat* or train* or teach* or competenc* or skill* or procedur* or surg* or operat* or resuscitat* or life-support or ACLS or BLS or PALS or CPR or chest-compression* or arrest or defibrillat* or cardiopulmonary-rescue).ti,kf. | 1,937,367 |

| 24 | 22 and 23 | 5,995 |