Simulation training is a teaching method which uses a controlled environment to “recreate a clinical experience without exposing patients to the associated risks” and allows students to practise skills and gain confidence in clinical scenarios [1]. Simulation training is highly effective at enhancing the learning and clinical competency of individuals working in a healthcare setting [2]. Over the past year we, a group of FY2 doctors, delivered “virtual on-call” sessions for final year medical students and foundation doctors, providing them with bleeps and a simulation of an on-call shift.

Teaching sessions were run for groups of up to 18 students/foundation doctors. Feedback was gained before and after the sessions both verbally and with a written form. Three cycles were completed, using feedback to make adjustments and optimise the delivery of virtual on-call teaching. Sessions were delivered to 1 cohort of 31 new FY1 starters, and to 5 different cohorts of 64 final year medical students across the year. All 12 sessions were run in a single centre (a rural district general hospital).

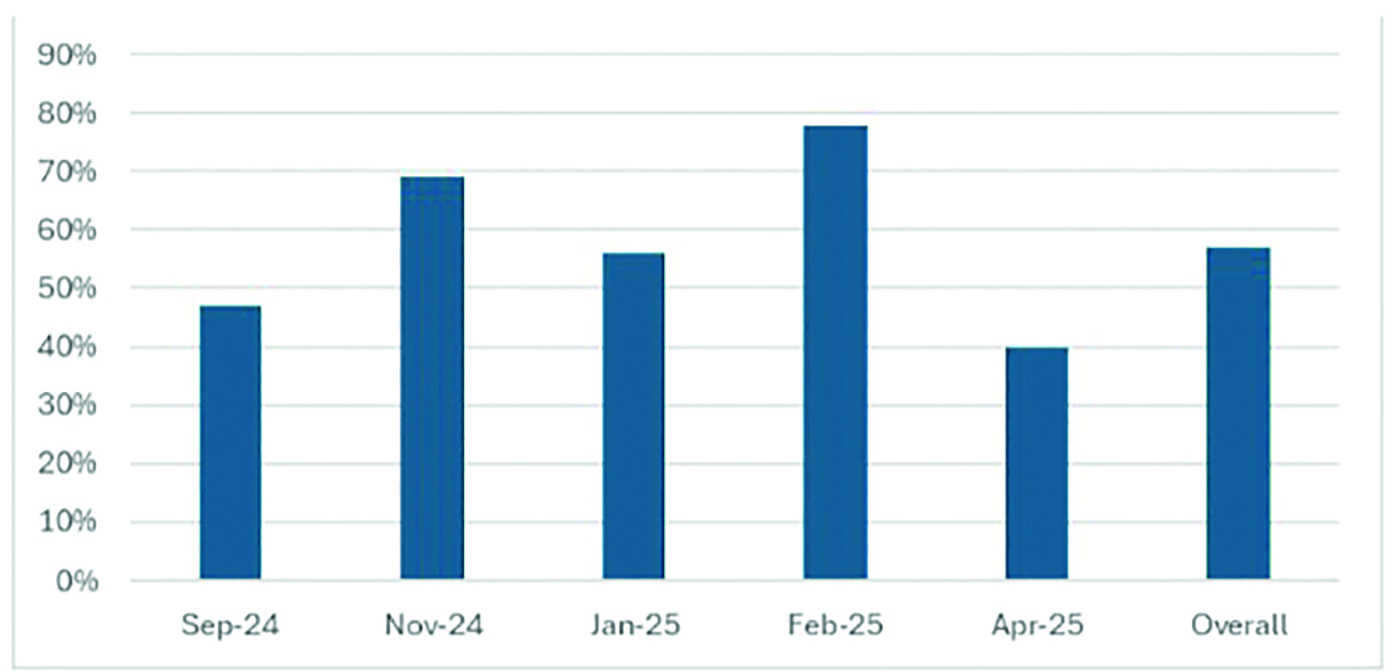

The number of students feeling confident about on-calls increased after all teaching sessions (Figure 1), with a more than 50% overall increase in subjective confidence. With the addition of a contactable ‘med reg’, there was also a significant increase in confidence using SBAR handovers and escalating to seniors. The overall feedback was overwhelmingly positive with comments such as “Would love more sessions like this”, “Really great, please do more of these sessions”, and “The best teaching session we’ve had during med school”.

Virtual on-call simulation teaching is a very valuable resource for developing confidence on-call in final year medical students and new foundation doctors. Learning from feedback is crucial to improving the quality of the teaching and producing better outcomes for the students. Key components that increased students’ confidence included providing the opportunity to bleep for advice, instead of simply verbalising that intention, as well as adding facilitated elements to enable direct feedback. Developing a structured introduction to the sessions helped them to run smoothly and the students to get the best out of the experience. With the incredibly positive feedback for these teaching sessions being noticed by the medical school we are in the process of making this part of the final year curriculum for all medical students at Exeter Medical School.

As the submitting author, I can confirm that all relevant ethical standards of research and dissemination have been met. Additionally, I can confirm that the necessary ethical approval has been obtained, where applicable.

1. Maran NJ. Glavin RJ. ‘Low- to high-fidelity simulation – a continuum of medical education?’. Medical Education. 2003:22–28.

2. Elendu C, Amaechi DC, Okatta AU, Amaechi EC, Elendu TC, Ezeh CP, et al. The Impact of simulation-based Training in Medical education: a Review. Medicine [Internet]. 2024;103(27):1–14. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11224887/

We would like to thank Dr Timothy Mason, who first introduced the concept and whose consistent support and enthusiasm encouraged us to develop the sessions. We also thank the whole NDDH Medical Education team and the Enhance team for providing resources and logistics help. We are also very grateful for those who have volunteered their time to help facilitate sessions over the year.