Meta-debriefing, otherwise known as ‘debriefing the debrief’, offers simulation faculty an ongoing opportunity to iteratively develop their debriefing skills. Online meta-debriefing provides a uniquely accessible format that supports geographically dispersed simulation educators, fosters diverse perspectives, and enables sustained professional development opportunities beyond traditional in-person constraints. Drawing upon our experience as a diverse team tasked with setting up the Association for Simulated Practice in Healthcare (ASPiH) Meta-Debrief Club, here we present eight practice guidelines, or ‘tips’, to support online meta-debriefing. These tips are aligned with the four fundamental pillars that underpin meta-debriefing practice and can be adapted to various contexts and platforms.

Debriefing is a dynamic process which requires the facilitator to closely listen, adeptly guide, and efficiently maximize the learning conversation – all whilst maintaining a strong sense of emotional intelligence towards the tone and ‘temperature’ of the group [1–4]. Whilst faculty development courses that support initial and intermediate development of debriefing skills are commonplace, the same cannot be said for those that support ongoing debriefing ‘maturation’ [5]. Meta-debriefing has been promoted as one strategy which offers a longer-term, formative approach to developing proficiency in debriefing [6].

Meta-debriefing, defined as ‘a facilitated learning conversation enabling debriefers to review and critically reflect upon their own or others’ debriefing practices’, can be practised in various ways, and across a spectrum of contexts [6]. Here we build upon one approach that has gained significant attention – an online Meta-Debrief Club (MDC) [7]. The MDC utilizes a Communities of Practice approach [8], where participants meet at an assigned time and away from the simulation event itself, to watch a video-recorded debrief which is followed by a debrief of the debrief [7,9]. The aim of the MDC is not only to benefit the person who shares their debrief (as formative feedback of their practice), but also to provide learning for the entire group of fellow participants.

What began as an in-person approach, the COVID-19 pandemic necessitated a salient shift for one meta-debriefing group to explore the virtual setting [7]. This online approach has been adopted by the Association for Simulated Practice in Healthcare (ASPiH) to provide debriefers with ongoing developmental opportunities, especially for those in isolated settings or without the infrastructure advantages of more established simulation services. Whilst we acknowledge the well-documented challenges associated with online approaches to learning (such as reduced learner engagement and motivation, technical and infrastructural issues and increased facilitator cognitive load [10,11]), we outline within this paper several strategies that may help mitigate some of these issues. Crucially, the online format removes geographical barriers, inviting national and even global participation. This fosters a diverse community where a wide variety of debriefing practices are shared and exchanged, supporting critical discourse and the broadening of perspectives that is key to developing expertise beyond the cultural confines of a single centre.

Drawing upon our collective experience in launching a national, virtual, MDC for ASPiH, we present a set of eight tips to support online meta-debriefing. We intentionally offer these as ‘tips’ rather than ‘practice guidelines’ to acknowledge individual contexts and allow maximal local flexibility.

As authors, we draw from diverse backgrounds, experiences and disciplines. NO and CLC come from a nursing background, whilst DOF, CH, BT and PK are doctors. The team has a varied wealth of simulation, debriefing and meta-debriefing experience, across a range of contexts, organizations and locations. A shared element is our strong interest in debriefing and desire to be more skilled and effective in what we do. We also all hold a range of leadership and faculty development responsibilities, which requires us to think deeply about how we cultivate debriefing expertise within our teams. CLC has recently completed her term as President of ASPiH, and remains part of the ASPiH Executive Committee, along with NO and DLO. CLC, NO, DLO and PK are co-chairs of the ASPiH Debriefing Special Interest Group, which oversees the delivery of the ASPiH MDC. Additionally, PK is currently leading a programme of scholarship exploring meta-debriefing practice across varying contexts and NO is exploring the development of expertise in debriefing, both as part of their respective ongoing doctoral studies.

These tips are explored within the four pillars of meta-debriefing as described by Kumar et al. [6]. The authors posit that regardless of approach, effective meta-debriefing practice shares these common pillars of practice: theoretically driven, psychologically safe, context dependent and formative in function [6] (see Figure 1). It is important to note that whilst our tips are numbered below, we do not mean this to convey an order of priority or significance. We also acknowledge that when discussing meta-debriefing, the noun ‘debriefer’ can quickly become confusing to the point of exasperation! When discussing meta-debriefing, the ‘debriefer’ could refer to the person who has submitted their debrief footage, or else it could refer to the person facilitating the meta-debrief. For clarity, within this paper we will refer to the ‘debriefer’ as the person who is sharing their video footage, and the facilitator (or facilitators) as the person leading the meta-debrief session.

![The pillars of meta-debriefing practice, from Kumar et al. (used with permission from Wolters Kluwer Health) [6]](/dataresources/articles/content-1770808805565-9a42fea4-ee1d-41cc-a74d-3ccddf0572ce/assets/gmft2275_f001.jpg)

The pillars of meta-debriefing practice, from Kumar et al. (used with permission from Wolters Kluwer Health) [6]

Situating an online MDC as a community of practice helps refine debriefing expertise through peer interaction, mutual engagement and joint enterprise [8,12]. A collaborative environment, which is central to social constructivism [13] enables participants to engage in shared meaning-making and knowledge construction. This creates a structured, supportive and dynamic learning environment where individuals can feel comfortable sharing debriefing experiences, providing feedback and engaging in critical discourse. This safe environment is built upon the principles of psychological safety (Tip 3). To foster this, facilitators encourage open dialogue and the co-creation of debriefing strategies by presenting challenging debriefing scenarios and video excerpts for shared analysis. The club also supports observation-based learning by creating a welcoming environment that explicitly legitimizes peripheral participation, for example, by allowing participants to maintain camera-off settings or contribute however they feel comfortable [8]. We acknowledge the inherent risk in this approach, for example, that by readily allowing participants to have their camera off we might introduce unintended psychological safety and engagement related consequences to other members of the group. We attempt to mitigate such risks by being explicit in the ‘welcome’ section of each meeting, offering regular invitations to participate peripherally in anticipation of more active engagement as they find their feet.

Whilst experience can build confidence, it does not guarantee the development of expertise [14,15]. Engagement in a reflective process is crucial [15,16]. In the context of meta-debriefing, this process is most effective when it fosters critical reflection on the underlying assumptions, beliefs and knowledge that inform debriefing practices [6]. This process aims to foster cognitive presence, where learners construct meaning through sustained virtual discourse [17]. The MDC offers a structured approach which begins with watching debriefing footage as a launch pad. Facilitators then guide critical reflection using open questions and inviting alternative perspectives on themes observed in the clip. To support this process, facilitators demonstrate flexibility in their approach to cater for the varied levels of expertise [18]. A learner-centred approach, for example, may focus on structured models for novices whilst using more nuanced question styles to challenge the assumptions of experienced debriefers. This nurtures the development of a shared repertoire of resources, including debriefing-specific methods, techniques and practices [12].

Establishing a sense of psychological safety is crucial for ensuring participants feel prepared to contribute meaningfully within an online community of practice [19,20]. This approach aligns with building social presence, a key strategy for effective online debriefings [17]. However, the online environment presents some unique challenges to building rapport, such as the lack of body language, delays in ‘one-at-a-time’ speaking and real-time fluctuations in attendance. To mitigate these issues, facilitators intentionally design and manage the space [20,21]. For the debriefer sharing their debrief footage, a pre-session connection is necessary to build rapport and encourage them to self-identify a specific aspect of their debriefing practice for the community to focus on [5]. Each MDC begins with introductions and a briefing that outlines the purpose, aims, and order of proceedings – setting a clear and supportive tone. Active role-modelling of positive body language through expression and active listening encourages participants to mirror these behaviours. To foster a safe learning environment, we invite participants to share something about themselves, such as their location, time zone or an emoji/meme in the chat. For larger groups, we utilize facilitated breakout rooms to foster more meaningful interactions.

Co-facilitation is a crucial strategy for managing the cognitive load of the online environment, which in turn supports psychological safety (Tip 3) for both the facilitators and the participants [22]. Managing both a live discussion and a real-time text chat is cognitively demanding and often erodes the ability to actively listen. A co-facilitator allows for a distributed workload, with one person monitoring the chat, tracking participant engagement and handling technical issues. This enables the primary facilitator to remain fully present, responsive and focused on the conversational flow, which is essential for a successful meta-debriefing session.

The intentional 1-hour length of the MDC, designed for busy clinicians and educators, makes a repository of short, ready-to-go debrief clips a valuable resource. It has been noted that whilst newer members are often willing to attend sessions to learn, they are often hesitant to share their own debriefs. This collection of pre-recorded debriefing topics provides facilitators with the flexibility to adapt to unforeseen circumstances, such as a debriefer’s last-minute cancellation or technical disruptions. It also enables the curation of more nuanced discussions which can be signposted in advance, for example a session on ‘managing challenging emotions’ or ‘asking insight generating questions’. A key challenge to building a repository is sourcing material from the community. We have encouraged members of the community to share their own videos through multiple strategies, including running workshops at conferences, social media activity and by designing a clear video consent template which participants can use within their own local contexts. Participants can then contribute their videos and store them securely on the ASPiH Microsoft Teams™ channel prior to the MDC session. To promote a culture of professional vulnerability and to encourage inclusive participation (Tip 7), MDC facilitators can role model this behaviour by contributing their own debriefs. By demonstrating a willingness to be peers in the learning process, a foundation of trust can be established.

Momentum is difficult to generate and even harder to maintain, especially in the time-poor context of healthcare education [23]. To maintain momentum and avoid frustrating members, a consistent schedule and the avoidance of cancellations is advocated. A range of MDC events covering various days and times provides greater opportunities for colleagues to attend, particularly for those working in different contexts and geographical locations, supporting a more diverse membership. We acknowledge however that arranging suitable times across different international time zones is an ongoing challenge, and one that organizers should be mindful of. Maintaining a consistent presence and engaging in regular communication is also crucial for sustaining momentum. This can be achieved by circulating a calendar of upcoming sessions and providing a brief session summary via e-mail or other communication channels to encourage repeat attendance.

A common barrier to engagement in meta-debriefing is the erroneous notion that one must have expertise in debriefing before graduating into meta-debriefing. We disagree. Cheng et al. suggests self-reflection and peer feedback – both key aspects of the MDC – as faculty development strategies across all stages of debriefing expertise (discovery, growth and maturity) [5]. The MDC is a valuable approach for all levels of experience [5]. It is not a space for the ‘elite’, but for the engaged; not for summative examination, but for formative exploration. Participants at all stages of their debriefing journey are welcomed by fostering an environment with a flattened hierarchy, shifting the focus from individuals to the group. Importantly, this should include groups whose primary role may not lie within education, such as full-time clinicians or other patient-facing roles, as their contribution is frequently valuable to the learning conversation. We recommend that this ethos be explicit in communications to potential participants when advertising MDC sessions. MDCs are not so much about the performance of the debriefer but more of a collaborative learning experience that differs from individual reflection (Tip 2) by explicitly focusing on what all members can learn through a shared examination of the debrief.

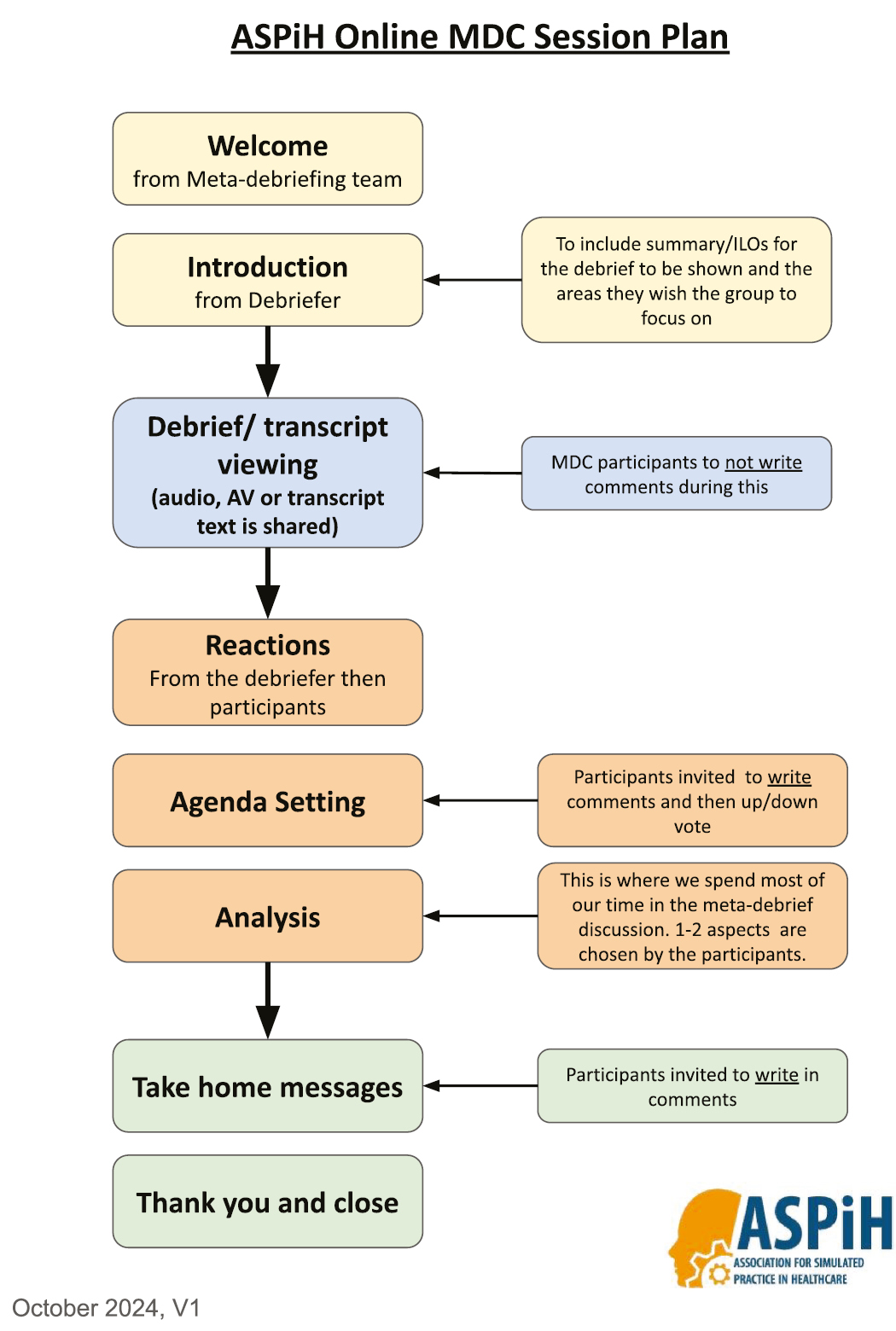

Maintaining a structured, but flexible format for MDC sessions is a crucial practice, particularly when facilitating larger groups on a virtual platform. This practice is a key manifestation of teaching presence – the facilitator’s role in orchestrating and guiding successful virtual debriefings [17]. The structured format creates a shared mental model for the session and guides the group towards a shared formative discussion. As Sawyer et al. noted, the ‘best’ debriefing method is often context dependent [24]. Within the context of this MDC, a format that works well has been iteratively developed, largely drawn from the Scottish Centre model of debriefing (Figure 2) [25]. The meta-debrief begins by validating initial ‘reactions’ from the debriefer and the group. The text chat function is then used to facilitate ‘agenda setting’, with members invited to share their observations and ideas in a plus/delta format [25]. The group then ‘up-votes’ suggested areas to be explored further as the meta-debrief progresses into the ‘analysis’ phase. During this phase, members contribute to the conversation verbally, sharing their own stories, experiences and debriefing strategies. This dialogue is enriched by the exchange of perspectives, enabling the critical discourse and questioning of assumptions described in Tip 2. The session concludes with a sharing of ‘take home messages’, which are typically members’ own reflections and learning points shared back in the text chat [25]. Additional debriefing tools, like DASH [26] and OSAD [27] are frequently experimented with, and flexibly used, to shape a formative conversation [26,27]. With scoring aspects removed, these tools serve as visual aids and conversation starters to support the formative approach.

The ASPiH MDC format

These practice guidelines have been developed, based on our experience, to support the development and delivery of online MDCs within your department or team. If there is one key takeaway to communicate to a simulation community interested in developing its own online MDC, it is this: both debriefing and meta-debriefing require a complex and nuanced skillset and are highly cognitively demanding. Whilst it is not advised for novice debriefers to facilitate an MDC until comfortable with their own debriefing practices, facilitating an MDC does not require perfection or advanced expertise, but rather a commitment to reflective practice and collaborative learning. The eight tips offer concrete strategies for cultivating the reflective and collaborative environment essential for a successful MDC. Simulation departments and teams are therefore encouraged to explore how an MDC, or meta-debrief approach in general might become a regular, embedded and supportive process. It is acknowledged that as an approach, the MDC is not yet well-evidenced and would strongly benefit from robust research exploring its impact on both the facilitation approaches of faculty and its impact on learners. More research is also required to explore the optimal context in which to deliver MDC activities and from whom, when and how often is most beneficial.

The authorship team would like to acknowledge the work of the ASPiH Meta-Debrief Club steering group, particularly Dr Ed Mellanby, Dr James Nicholson, Dr Efthymia Kapasouri and Dr Joel Burton. We would especially like to acknowledge and celebrate both the members of the ASPiH Meta-Debrief Club, alongside the growing number of others starting in the UK, Africa and Australia.

The Association for Simulated Practice in Healthcare (ASPiH) have supported the publication of this work through their fee waiver member benefit.

NO led the authorship team. NO and PK conceptualized the project in its early phases. All authors contributed to the guideline formation and content. All authors were involved in manuscript preparation, with BT offering additional key editing work at the latter end of the project. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. CLC, NO and DOF are executive committee members of the Association for Simulated Practice in Healthcare (ASPiH). CLC, NO, DOF and PK are co-chairs of the ASPiH Debriefing Special Interest Group, which oversees the delivery of the ASPiH Meta-Debrief club. All authors are active members of ASPiH.

None declared.

None declared.

None declared.

None declared.

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.