The process of learning how to perform a clinical procedure in health care has been described as diffuse and uneven, and based on available opportunity. This ad-hoc approach to learning can lead to variability in task performance and negatively impact patient safety and quality of care. Hierarchical Task Analysis (HTA) is a method that can be used to establish a standard for completing a clinical procedure, which can be used for simulation-based education and assessment purposes. HTA provides a systematic and structured approach to deconstructing a clinical procedure into what the learner needs to do, in what order and the conditions that are required at each step. HTA is not commonly used in health care. However, it has great potential as a method to allow for the standardization of clinical procedures. The outputs of HTA can be used in simulation-based education for assessment and the validation of training and assessment.

Key points

•Hierarchical task analysis (HTA) is a human factors method that supports the identification of an agreed standardized approach for performing a clinical procedure to support teaching and assessment.

•HTA is a user-centred approach that focuses on delineating what a learner needs to do, in what order and the conditions that are required at each step.

•HTA is one of the most widely used human factors methodologies, and although commonly used in other industries, it is not widely used in health care.

•The output of HTA can be used for both training and assessment purposes.

•In addition to being valuable for supporting educational activities, HTA can also support the identification and mitigation of the risks associated with particular steps in a procedure.

The process of learning how to perform a clinical procedure in health care has been described as diffuse and uneven, and based on available opportunity [1]. This is an inefficient approach to learning, which can lead to variability in the performance of procedures. While variability is not always negative, there should be an accepted and agreed ‘standard’ approach from which deviations can be justified. Standardization supports better team and task performance and patient safety and quality of care. Once familiar with the standard approach, healthcare providers will be in a better position to question and justify deviations from the standard. Evidence suggests that standardizing task performance has the potential to improve patient care and patient outcomes, reduce length of stay and reduce healthcare expenditure [2]. However, for many clinical procedures, there is a lack of an established evidence-based and agreed standard for task performance.

Human reliability analysis methodologies from the discipline of human factors/ergonomics provide a wide range of methods that can be used to analyse tasks [3]. A task analysis is a particular human reliability approach that can be used to establish a standard for completing a clinical procedure. In this paper, we will outline the use of a particular approach called Hierarchical Task Analysis (HTA). The hope is that the insights into this process will encourage the broader use in simulation-based education (SBE).

A task analysis is an approach that systematically breaks down an activity into its component steps that must be carried out in order to complete the task. Task analyses can be organized and presented in different ways, but a common method is to arrange information hierarchically [4,5]. HTA has been described as the most frequently used human factors and ergonomics method [6]. HTA allows the operator to systematically and objectively identify and delineate the actions to be taken to achieve a procedural objective or task. The ‘task’ in HTA is somewhat misleading. The HTA does not actually focus on the task per se, but rather involves the identification of a series of sub-goals required to meet the overall goal of completing the task [7]. HTA is a user-centred approach that focuses on delineating what the user needs to do, in what order, and the conditions that are required at each step [6].

HTA techniques have great potential to support SBE through the identification of the steps required to complete a procedure, and support a competency-based approach to health professions education. The identification of the steps in a clinical procedure is fundamental to behavioural learning methodologies such as fluency training [8], deliberate practice [9] and mastery learning [10]. The output of the HTA can be used as a framework to assess the competency of those learning the procedure. Moreover, an HTA can be used to support the ‘validity argument’ that the assessment decision and interpretations are defensible [11].

Despite the potential of HTA for proceduralizing and standardizing complex tasks, they are infrequently used in health care. Where HTA has been undertaken in health care, it has tended to be in task focused specialties such as critical care (e.g. preparing and delivering anaesthesia [12], endotracheal suctioning [13], bronchoscope-assisted percutaneous dilatational tracheostomy [14], intercostal drain insertion [15]) and surgery (e.g. functional endoscopic sinus surgery [16], endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty [17], cricothyroidotomy [18]).

There is no one single agreed approach to conduct HTA [19]. We describe an approach that has commonly been used in health care), and is consistent with the basic heuristics for carrying out an HTA described by Stanton [19]. This method was selected due to its clarity, compatibility with educational purposes, and widespread use in the human factors and HRA literature. This approach is described as a series of seven steps (see Table 1).

| Step 1. Identify the purpose of the HTA | Identify the user population and the intended end purpose of the HTA. |

| Step 2. Identify the boundaries of the HTA | The start point, end point and scope of the HTA should be established. |

| Step 3. Gather information for the HTA using more than one source of information. | Source of information can include a combination of sources such as a literature review, observation and interviews. |

| Step 4. Identify and describe the system goals and sub-goals. | Develop a hierarchy of sub-goals required to complete the task. |

| Step 5. Link goals to sub-goals, and describe the conditions under which sub-goals are triggered. | Outline the conditions under which goals are executed, and guide the order and selection of the subordinate goals and sub-goals (i.e. the plan). |

| Step 6. Establish the number of sub-goals required. | Obtain consensus on the level of detail and granularity of the HTA. |

| Step 7. Refine the HTA. | The final HTA should be reviewed by independent experts to ensure the HTA represents ‘a correct’ way. |

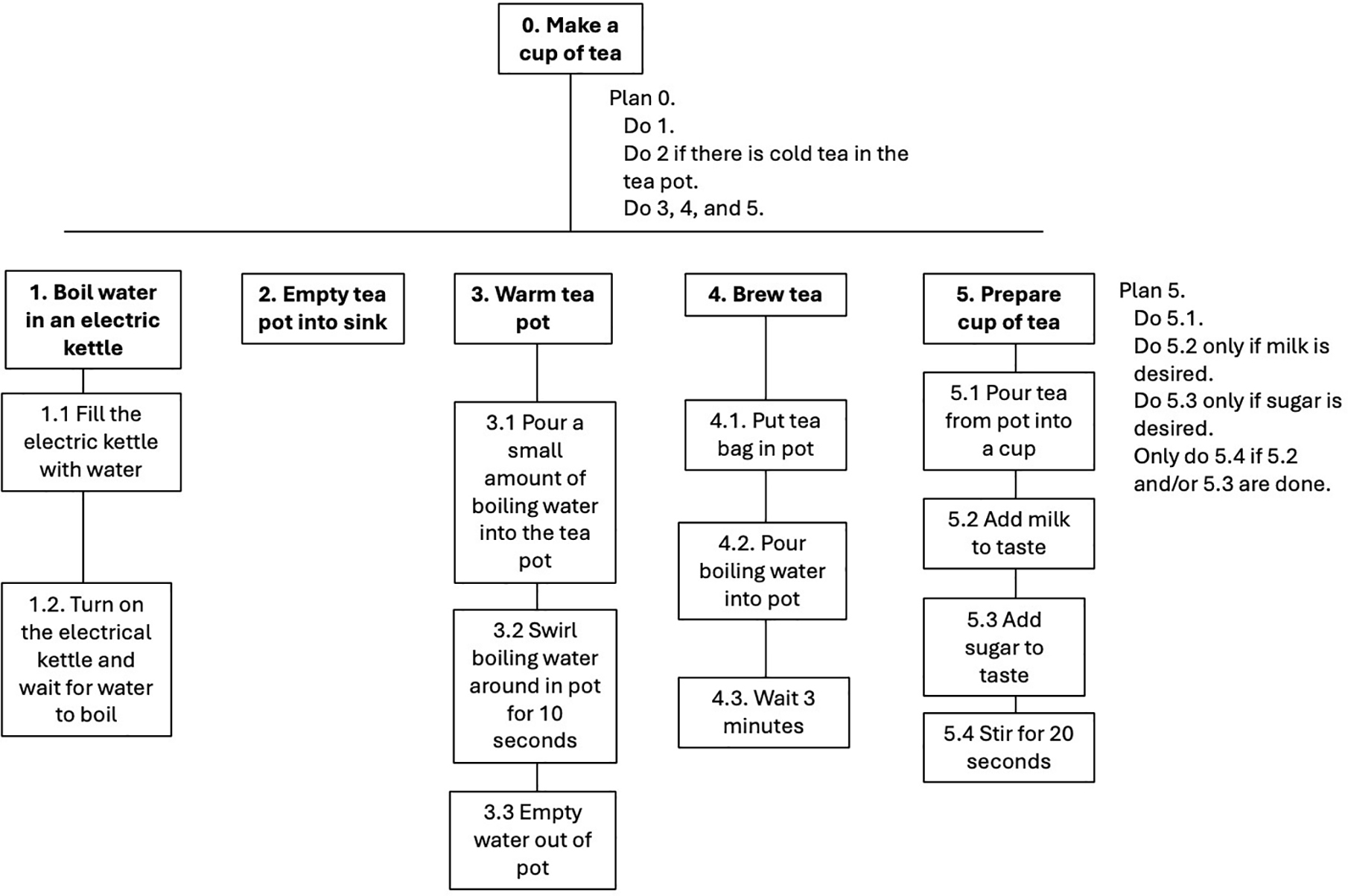

HTA is often undertaken for tasks that are complex, error-prone and where the procedural guidelines that currently exist are insufficient for training or assessment purposes. Once the target procedure for the HTA has been identified, there is a need to consider the purpose of the HTA. In health care, the purpose of an HTA is often to guide training in how to undertake a procedure and for evaluation and/or assessment purposes. However, an HTA can also be used to identify new ways of working (e.g. to describe the steps involved in integrating a new medical device into a process). The end user of the HTA should be considered from the outset. For example, if the intended users are nursing students, the level of detail provided at each stage may be greater than if the intended users are experienced nurses. Readers who wish to see a simple example of a healthcare HTA are directed to Phipps et al. [12]. These authors present an HTA of how to set up an intravenous infusion pump. In this article, we have elected to use an example out of a healthcare context in order to emphasize the process rather than the clinical information. The target procedure we have chosen is how to make a cup of tea (see Figure 1). This pictorial approach is one way of representing the HTA. An HTA can also be represented in a more tabular format – this is probably preferable if the HTA is to be used for assessment.

Example HTA of making a cup of tea

Clear boundaries for the HTA must be established. The start and end points of the procedure must be decided. In the tea-making example, the start point is boiling the water to make the tea, and it ends with the preparation of a cup of tea in a domestic setting. Additionally, the focus of the HTA can be on a particular part of the clinical procedure. In the tea-making example, it could be ‘brew the tea’, while in the intravenous infusion example, it could be ‘clean the skin’ or it may include the preparatory steps preceding the intravenous insertion (e.g. positioning and draping the patient). The focus of the HTA may be on one individual (e.g. the anaesthetist) or on an entire team (e.g. the clinical team). Focusing on a team task highlights that HTA can be used to describe all the elements comprising safe performance of the clinical task – psychomotor skills, handling instruments, arrangement of space, teamwork, communication and more.

It is recommended that more than one source of information is used to derive an HTA [19,20]. The tea-making HTA was based upon our own experience and observations of others, making a cup of tea (see Figure 1). In health care, the sources of information have generally included: (1) a literature review; (2) observation and (3) interviews with subject matter experts. The purpose of the literature review is to identify whether there is existing published guidance on how to carry out the procedure. The literature review may include a search of the research literature, but should also include the grey literature, textbooks and any available guidelines that describe how to perform the task. Observations of experts performing the procedure is a very valuable source of information. These observations could be in the real clinical environment, but alternatively and/or additionally, could be performed in a simulated setting. It is useful for the individual being observed to ‘speak aloud’ whilst performing the task to provide the observer with information not just on the physical steps but also on the cognitive considerations involved in the performance of the task. These cognitive considerations are represented in the goals and plans of the HTA. Interviews with experts are another potential source of information about how the clinical procedure is performed.

The overall aim of an HTA is to develop a hierarchy of subgoals for the task under scrutiny. This hierarchical approach necessitates the identification of the superordinate or overall goal of the HTA, and then this goal is divided into a series of subordinate goals that must be completed to meet the overall goal. In Figure 1, the goal of making a cup of tea has been divided into five subordinate goals. Depending on the task, there may be a need for further subgoals. When defining these goals, consideration should be given to the active verb that is used to describe the action. Any standards or conditions associated with the goal (e.g. complete within a particular time period) should be clearly defined.

It is recommended that the number of sub-goals under a particular goal should be limited to between 3 and 10 – ‘there is an art to HTA, which requires that the analysis does not turn into a procedural list of operations’ (p.19) [19]. Therefore, if there are more than 10 sub-goals to a given goal, then consideration should be given to dividing the goal into 2 or more separate goals.

Plans are the control structure that outline the conditions under which goals are executed. Plans guide the order and selection of the subordinate goals and sub-goals. The plan describes the context under which particular sub-goals are triggered [19]. To illustrate, in Figure 1, plan 5 describes how to address the situation where the drinker of the tea desires milk and/or sugar in the cup of tea.

Deciding how much detail is required in an HTA is an important consideration and something that can be difficult to decide. The general guidance is to use the ‘P x C stopping rule’. This is a rough heuristic in which you stop breaking down sub-goals when the product of the probability of failure (P) and the cost of failure (C) becomes acceptably low, indicating a negligible risk [19]. However, it can be challenging to estimate the probability of failure and the cost of failure. A pragmatic approach to decide how much detail is required is to show the draft HTA to the intended users in order to receive feedback from them on whether more or less detail is required. The rationale for this approach is that the end users are best placed to decide the level of detail that is required and whether there is too much or too little detail. Such an approach also allows the structure of a specific HTA to remain, but the level of detail to be adapted depending on the experience of different user populations. In the tea-making example, we make the assumption that the user has access to, and knows how to use, an electric kettle.

The output of the HTA should be reviewed by experts who are experienced in carrying out the clinical procedure, but were not involved in the development of the HTA content. The purpose is to obtain feedback, make corrections and ensure that the HTA represents an agreed ‘correct way’ to complete the procedure. It does not matter if the experts themselves do not carry out the procedure exactly as it is delineated in the HTA, as long as there is agreement amongst them that the HTA represents an appropriate and safe approach to completing the procedure. Step 7 may require more than one review and often requires an iterative process to reach a final agreed approach to performing the procedure with an appropriate level of detail.

It may be that the person responsible for completing the HTA is also an expert in the procedure. If this is the case, it is still important to use multiple sources of information to carry out the HTA, as there are likely to be individual differences in task performance, and it is important to derive an agreed correct way of performing the procedure. HTA carried out in health care [12–18] and other settings [21] have adopted a purposive sampling strategy in which a relatively small number of people (4–10) who are experts in the procedures are deliberately recruited to participate and provide input on the HTA.

The focus of an HTA is on identifying the observable steps required to carry out a task. The HTA should be considered a living document. Changes in guidelines or equipment may mean the HTA must update to ensure that it continues to represent ‘work as done’ rather than ‘work as imagined’. Moreover, if the HTA is to be used in another unit or setting, expert input will be required to review, and possibly adapt, to the different working environment.

Although an HTA is an effective approach for identifying what needs to be done and how it should be done, there are a number of limitations of the HTA approach that should be acknowledged. Firstly, an HTA generally does not provide guidance on how to address any unexpected or unforeseen issues [21]. However, other techniques such as failure modes and effects analysis can be used in conjunction with the HTA output to help fulfil these requirements [15]. An HTA can also be used to support an assessment of the level of risk associated with each subgoal using approaches such as the systematic human error reduction and prediction approach (SHERPA) [12–14]. Secondly, HTAs identify the observable steps required to carry out a task. If there is a desire for a specific focus on the cognitive aspects of the task, then other methodologies are more appropriate, such as a cognitive task analysis (see Militello [22] for a discussion of this method). Finally, HTAs are generally carried out with only a small number of subject matter experts – often from the same workplace. This may be due to the length of time required to carry out an HTA, limited opportunities for observation and the potentially limited number of suitable experts [14]. Therefore, care must be taken when adopting an existing HTA in another setting. An assessment should be made as to whether any changes are needed to the HTA to ensure it represents how the task is performed in the new setting.

As competence-based approaches become increasingly common in healthcare education, there is a need to identify ‘a correct way’ for completing a clinical procedure to support both teaching and assessment. Although not commonly used in health care, HTA provides a systematic and structured approach to deconstructing clinical procedures. HTA provides a method for standardizing how clinical procedures are performed, and supports the reproducibility and validity of training design. We hope that this outline of how to complete an HTA will encourage the use of this method to support the delivery of SBE.

•Phipps D, Meakin GH, Beatty PC, Nsoedo C, Parker D. Human factors in anaesthetic practice: insights from a task analysis. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2008;100(3):333–43.

•Stanton NA. Hierarchical task analysis: Developments, applications, and extensions. Applied Ergonomics. 2006;37(1):55–79.

None declared.

None declared.

None declared.

None declared.

None declared.

The Association for Simulated Practice in Healthcare (ASPiH) has supported the publication of this work through their fee waiver member benefit.

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.