In the emergency departments, skin and soft tissue infections are highly common. Incision and drainage (I&D) are a critical procedural skill for emergency medicine trainees. Simulation-based training offers a practical and safe method for developing this skill. The objective was to assess the effectiveness of a newly developed, low-cost, ultrasound-compatible simulation model for abscess and cellulitis across four domains, including self-efficacy, fidelity, educational value and teaching quality, using the Michigan Standard Simulation Experience Scale (MiSSES).

A low-cost simulation model was developed using accessible materials such as Jell-O, psyllium husk, food colouring, povidone-iodine, and mayonnaise with maple syrup and used during structured training sessions. This model was employed in a prospective survey study among emergency medicine residents in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Participants completed the MiSSES, which assessed their self-efficacy, fidelity, educational value and teaching quality.

A total of 107 residents participated. High average scores were reported in all domains: self-efficacy (mean 4.54 ± 0.52), fidelity (4.59 ± 0.49), educational value (4.60 ± 0.50) and teaching quality (4.64 ± 0.52). There were no significant differences by gender or previous experience. However, third-year residents reported lower self-efficacy than others (p = 0.012).

The newly developed simulation model was well received by learners and rated highly for educational effectiveness. Findings support its potential utility in resident training programmes, though further evaluation is needed to assess long-term outcomes and compare against other training methods.

Skin and soft tissue infections (SSTIs) range from superficial cellulitis to deep necrotizing infections. Among these, superficial abscesses are particularly common and require timely and effective intervention. SSTIs account for a substantial number of emergency department (ED) visits [1]. In the United States, an estimated 34.8 million outpatient visits were recorded between 2005 and 2011, nearly a third of which occurred in ED settings [1]. Incision and drainage (I&D) remain the standard treatment for abscesses and is routinely performed in both outpatient and emergency care contexts. According to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data, cutaneous abscesses accounted for approximately 2% of all ED presentations. However, 0.9% of all ED patients underwent I&D procedures [2]. Inadequate drainage may result in infection spreading to other areas, and this emphasizes the need for procedural competency [3].

Clinical diagnosis of abscesses is increasingly supported by point-of-care ultrasound, which enhances diagnostic accuracy [4]. Evidence suggests that ultrasound can alter management in up to 50% of such cases, including by identifying occult abscesses or confirming their absence [5]. It has shown superiority to physical examination alone, especially in paediatric patients and in cases where induration obscures diagnosis [5]. Despite the procedural and diagnostic importance of I&D and ultrasound in SSTI management, there is a notable gap in standardized tools for teaching and assessing competency in these procedures. Most residency training programmes rely on a minimum number of supervised encounters and self-assessed confidence [6]. Research has shown that confidence does not always correlate with ability, and procedural proficiency varies widely among learners [6].

Simulation-based education provides a safe, structured and ethical alternative to live patient training. It is particularly critical in surgical or procedural education, where practice opportunities may be limited. Prior models for abscess simulation include animal tissue, cadavers, or more recently, synthetic and virtual reality simulators [7,8]. However, many such models are either expensive, non-reusable or not easily accessible, particularly in resource-limited settings. Previous studies have provided multiple low-cost models using different materials to simulate human tissue. In a study conducted at the University of Newfoundland, Canada, aloe vera cream was placed in a Ziplock bag to simulate purulent discharge, which was then inserted into a pork tenderloin secured with metal skewers to represent human tissue [9]. In another study at the University of Arizona, they filled a balloon with puréed bananas and apple baby food, and they put the balloons inside cadavers [10]. Various models have been proposed to simulate abscesses using a gelatin base mixed with psyllium, though they lack emphasis on durability for repeated procedures [11,12]. Recent innovations have explored low-cost and high-fidelity alternatives using commercially available materials. These models aim to mimic both the tactile and sonographic appearance of abscesses and provide hands-on training opportunities in ultrasound-guided I&D [13,14]. However, these are not yet standardized across institutions, including Saudi Arabia. The current project sought to design and evaluate a similarly accessible simulation model.

This study aimed to evaluate emergency medicine residents’ perceptions of a novel low-cost model using the MiSSES framework across four domains: self-efficacy, fidelity, educational value and teaching quality. The specific objectives are (1) to develop a cost-effective and reproducible model for ultrasound identification of abscesses and cellulitis; (2) to enable residents to practice I&D procedures using these models; and (3) to assess the benefits of this simulation training for residents through a validated survey. The study aims to improve hands-on skills and procedural competency in emergency medicine training by achieving these objectives.

This prospective survey-based educational study was conducted in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Participation was voluntary through an online survey, and all responses were anonymized. The study was conducted after residents completed both theoretical and practical simulation sessions. Ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of King Saud Medical City (IORG: IORG0010374).

All emergency medicine residents in Riyadh were invited to participate through direct recruitment at their respective training centres. The decision to evaluate the model using emergency medicine residents was intentional, as this group represents the primary target audience for procedural skill development. Residents who attended the full training session and completed the post-session survey were included in the analysis. Those who did not complete the session or declined participation were excluded. The estimated total population was 300 residents. A target sample size of 168 was calculated using Raosoft’s sample size calculator with a 95% confidence level and 5% margin of error. A non-random convenience sampling method was employed.

The training session was divided into two parts:

•Theoretical Component (20 minutes): A brief lecture covered essential principles of abscess pathophysiology, clinical diagnosis and ultrasound identification, with emphasis on key procedural steps for I&D.

•Practical Component (40 minutes): Residents practiced I&D on simulation models under direct faculty supervision. Real-time ultrasound imaging was used to enhance model realism. Each participant was given multiple opportunities to perform the procedure, receive feedback and visualize simulated abscess structures under ultrasound.

Similar low-cost models described in prior literature have been produced for approximately 0.45 SAR (0.12 USD) using simple materials like sponge, flour and rexine sheets for tactile I&D training [15]. Our model incorporates additional realism through layered soft-tissue simulation and ultrasound compatibility, resulting in a slightly higher cost. Based on local material prices in Saudi Arabia, the approximate cost of each model was 10 SAR (2.67 USD). The model was developed using low-cost and easily accessible materials based on previous literature on gelatin- and balloon-based abscess simulators. The design focused on creating realistic tactile and sonographic feedback rather than validating material superiority. This approach aligns with established healthcare simulation system design principles, emphasizing functional realism and learner engagement as Scerbo described [16]. Fidelity in this study refers to how accurately the simulation replicates real-world procedural environments, often used interchangeably with ‘realism’ in simulation literature [17]. Expert validation of fidelity and realism through subjective assessment was an important step in model development to ensure broader applicability and comparative efficacy.

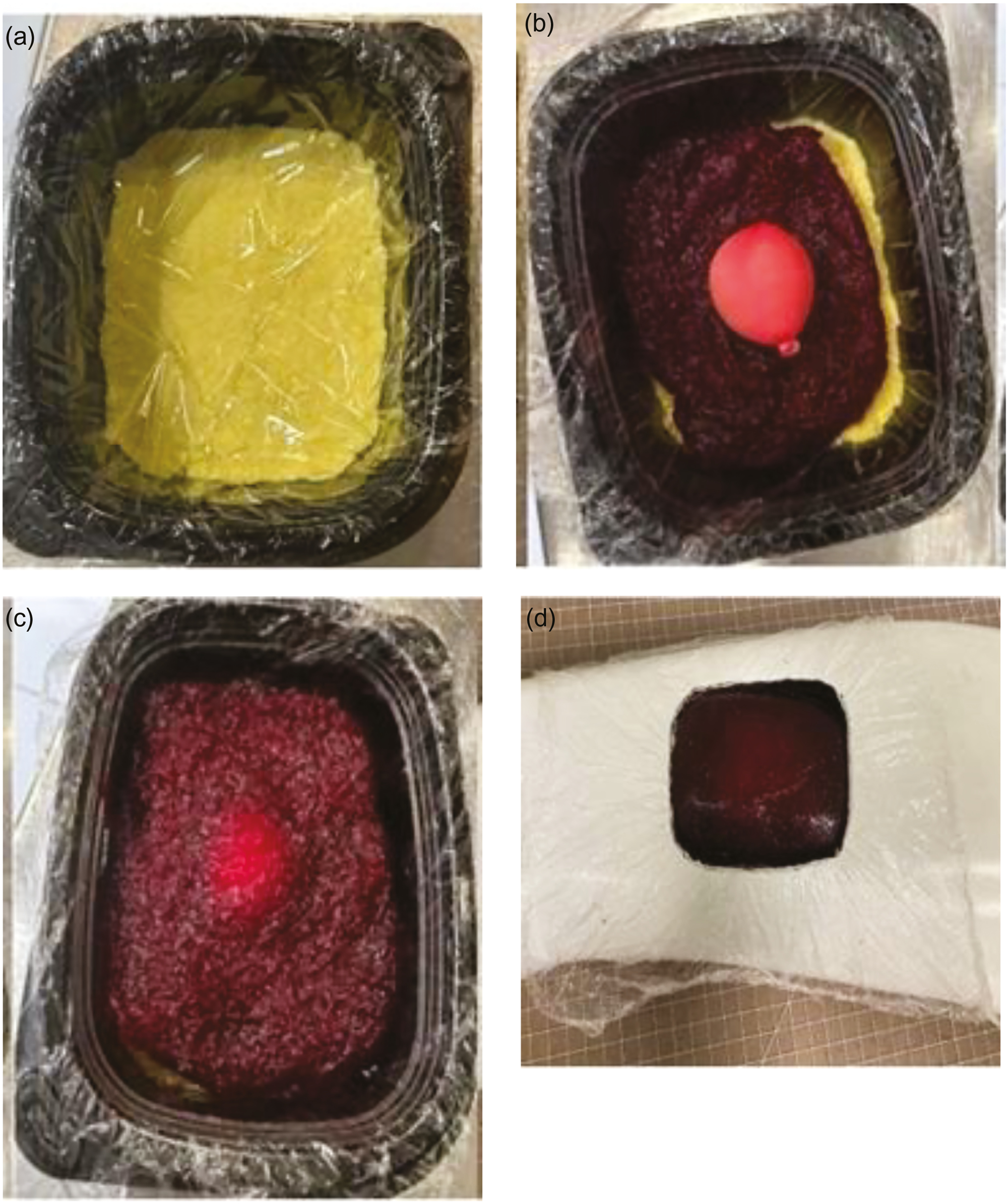

1.Base Layer: A square plastic cake pan was filled with kinetic sand to simulate structural resistance. It was covered with a plastic nylon sheet to separate the soft tissue layer, as shown in .

2.Soft Tissue Layer: A mixture of gelatin (Jell-O), red food colouring, psyllium husk and povidone-iodine was poured over the base to create a tissue-like surface. This combination was chosen for its balance of pliability, durability and sonographic clarity, consistent with prior low-fidelity models in the literature [1,2]. Balloon filled with a mayonnaise–maple syrup mixture is placed on top of the base before covering with simulated soft tissue, as shown in .

3.Abscess Cavity (Pus Simulation): Balloons were filled with a mayonnaise–maple syrup mixture to simulate pus, selected for its viscous consistency and realistic echogenic appearance on ultrasound, as shown in . Each balloon was embedded within the gelatin mixture before cooling in the refrigerator. After setting, the model allowed both palpation and ultrasound identification of abscess-like structures.

4.Final Assembly: The completed model was cooled and presented as a ready-to-use simulation tool, as shown in .

(a) Base layer construction. (b) Placement of simulated abscess balloon. (c) Application of soft tissue mixture. (d) Final simulation model ready for use

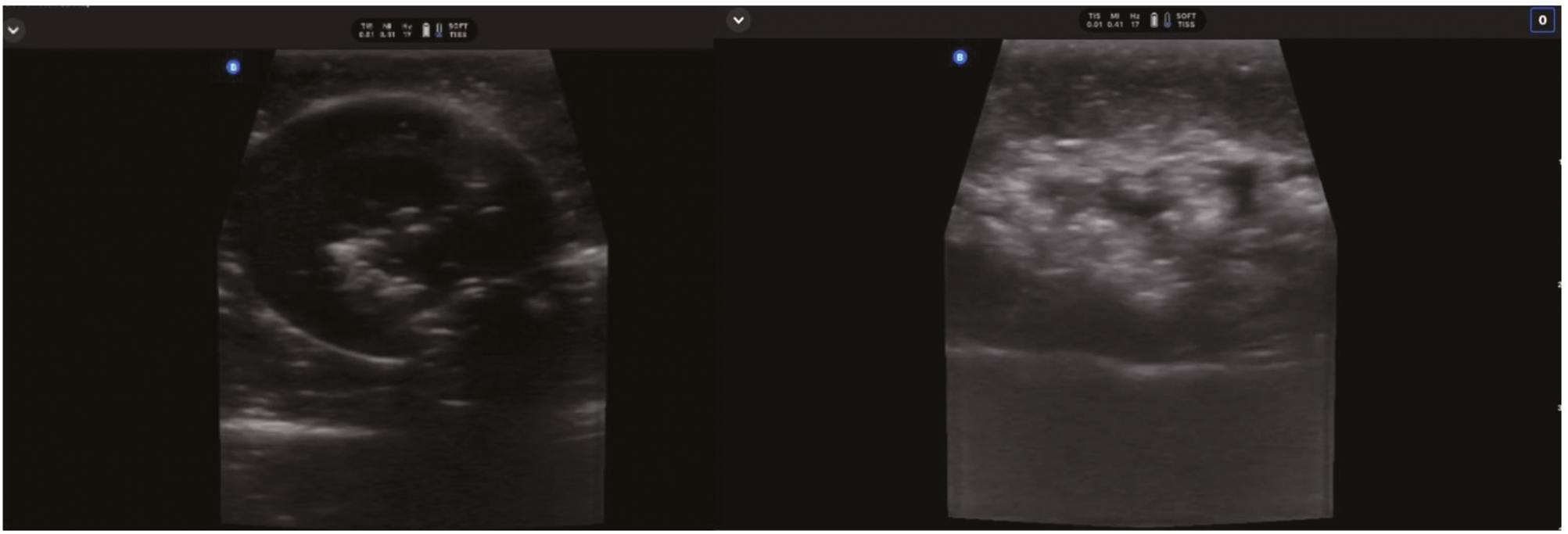

Although the materials used were inexpensive, no formal cost-effectiveness analysis or reproducibility testing was performed. The model’s primary purpose was educational to provide residents with a realistic and engaging simulation for ultrasound identification and I&D practice (Figure 2). Comparative claims or performance metrics were beyond the scope of this study.

Abscess and cellulitis model sonographic appearance on ultrasound

Data collection was carried out by administering an online survey to the participants following the simulation session. Data collection was performed by the co-investigators. We used the Michigan Standard Simulation Experience Scale (MiSSES), which provides a subjective measure of the validity of novel simulations [18]. The MiSSES survey, a validated tool that evaluates simulation experiences across four domains:

•Self-efficacy

•Fidelity

•Educational value

•Teaching quality

Responses were rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). Additional demographic information, including age, gender, year of training, and previous experience with I&D (real or simulated), was also collected. The survey was administered in online format by co-investigators.

Data were analysed using IBM SPSS Statistics (Version 27.0, Armonk, NY). Quantitative data were summarized as means, standard deviations, minimums and maximums. Categorical variables were reported using frequencies and percentages. Independent t-tests were used to compare means between two groups, while one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was applied for comparisons across three or more groups. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

A total of 107 emergency medicine residents from Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, completed the full simulation-based training session and post-training survey. As shown in Table 1, the majority of participants were male (75.7%), with a mean age of 26.9 ± 2.60 years (range: 22–33). Representation across training levels included 63.6% first-year, 12.1% second-year, 16.8% third-year and 7.5% fourth-year residents. Regarding prior procedural experience, 21.5% of participants had never performed an abscess I&D procedure, while 15.0% reported having done more than three such procedures previously. The distribution reflects a diverse range of clinical exposure levels across training stages.

| Variable | Frequency (n) | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Training year | ||

| First-year residents | 68 | 63.6 |

| Second-year residents | 13 | 12.1 |

| Third-year residents | 18 | 16.8 |

| Fourth-year residents | 8 | 7.5 |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 26 | 24.3 |

| Male | 81 | 75.7 |

| Prior abscess incision and drainage procedures performed | ||

| 0 | 23 | 21.5 |

| 1 | 45 | 42.1 |

| 2 | 12 | 11.2 |

| 3 | 11 | 10.3 |

| >3 | 16 | 15 |

| Age | ||

| Min–Max (years) | 22–33 | — |

| Mean ± SD | 26.9 ± 2.60 | — |

The MiSSES was used to evaluate residents’ perceptions of the simulation experience across four domains: self-efficacy, fidelity, educational value and teaching quality. Table 2 presents the detailed item-level responses.

| Domain/Item | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-efficacy domain | 5-point Likert scale | 4.54 | 0.52 | |||||

| The session improved my knowledge of I&D | 0/0% | 0/0% | 0/0% | 2/ 1.9% | 35/ 32.7% | 70/ 65.4% | 4.64 | 0.52 |

| The session improved my confidence performing I&D | 0/0% | 0/0% | 0/0% | 4/ 3.7% | 36/ 33.6% | 67/ 62.6% | 4.59 | 0.57 |

| The session improved my ability to perform I&D | 0/0% | 0/0% | 0/0% | 5/ 4.7% | 40/ 37.4% | 62/ 57.9% | 4.53 | 0.59 |

| The session improved my ability to perform I&D independently | 0/0% | 0/0% | 0/0% | 11/ 10.3% | 41/ 38.3% | 55/ 51.4% | 4.41 | 0.67 |

| Fidelity domain | 5-point Likert scale | 4.59 | 0.49 | |||||

| The simulator had realistic characteristics/features | 0/0% | 0/0% | 0/0% | 4/ 3.7% | 31/ 29% | 72/ 67.3% | 4.64 | 0.56 |

| The simulation environment was adequately realistic | 0/0% | 0/0% | 0/0% | 5/ 4.7% | 38/ 35.5% | 64/ 59.8% | 4.55 | 0.59 |

| Realism of abscess and cellulitis was adequate | 0/0% | 0/0% | 0/0% | 6/ 5.6% | 35/ 32.7% | 66/ 61.7% | 4.56 | 0.6 |

| Ultrasound identification of abscess/cellulitis was realistic | 0/0% | 0/0% | 0/0% | 4/ 3.7% | 35/ 32.7% | 68/ 63.6% | 4.6 | 0.56 |

| Educational value domain | 5-point Likert scale | 4.6 | 0.5 | |||||

| The simulation helped build knowledge of I&D | 0/0% | 0/0% | 0/0% | 3/ 2.8% | 37/ 34.6% | 67/ 62.6% | 4.6 | 0.55 |

| The simulation helped build procedural skills in I&D | 0/0% | 0/0% | 0/0% | 1/ 0.9% | 34/ 31.8% | 72/ 67.3% | 4.66 | 0.49 |

| The simulation effectively addressed I&D learning objectives | 0/0% | 0/0% | 2/ 1.9% | 4/ 3.7% | 33/ 30.8% | 68/ 63.6% | 4.56 | 0.66 |

| The simulation helped identify abscess/cellulitis using ultrasound | 0/0% | 0/0% | 0/0% | 7/ 6.5% | 32/ 29.9% | 68/ 63.6% | 4.57 | 0.62 |

| Teaching quality domain | 5-point Likert scale | 4.64 | 0.52 | |||||

| Instructors were knowledgeable | 0/0% | 0/0% | 0/0% | 0/0% | 27/ 25.2% | 80/ 74.8% | 4.75 | 0.44 |

| Instructors effectively conveyed material | 0/0% | 0/0% | 0/0% | 0/0% | 25/ 23.4% | 82/ 76.6% | 4.77 | 0.43 |

| Learning materials improved understanding of I&D | 2/ 1.9% | 0/0% | 0/0% | 10/ 9.3% | 28/ 26.2% | 67/ 62.6% | 4.46 | 0.9 |

| Session resources improved understanding of the simulation | 1/ 0.9% | 0/0% | 0/0% | 6/ 5.6% | 29/ 27.1% | 71/ 66.4% | 4.57 | 0.74 |

Note: Responses were recorded using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly Disagree, 5 = Strongly Agree). 0 = ‘Don’t Know’.

The overall mean score for the self-efficacy domain was 4.54 ± 0.52, indicating generally high confidence following the simulation. Among the four self-efficacy items, the highest-rated item was the abscess I&D session helped improve my knowledge (4.64 ± 0.52). Whereas the lowest-rated item was, the session helped improve my ability to perform abscess I&D independently (4.41 ± 0.67). These findings are supported by Table 2, which shows the item-wise score distribution. The score distribution suggests that while residents felt their knowledge and basic procedural confidence improved, their perceived readiness to perform the procedure independently remained slightly lower.

Participants rated the simulation model favourably in terms of realism. The mean fidelity domain score was 4.59 ± 0.49. Item scores included, the simulator has adequately realistic characteristics/features (4.64 ± 0.56). The simulation environment is adequately realistic (4.55 ± 0.59). Realism of abscess and cellulitis was adequate (4.56 ± 0.60). Realism of ultrasound identification of abscess and cellulitis was adequate (4.60 ± 0.56). These ratings, as detailed in Table 2, reflect a strong perception of realism in both tactile and sonographic dimensions of the model.

The educational value domain produced an overall mean of 4.60 ± 0.50. Participants gave high ratings across items focused on knowledge and skills enhancement. The simulation is a good training tool for skills in abscess I&D (4.66 ± 0.49). The simulation is a good training tool for knowledge in abscess I&D (4.60 ± 0.55). The simulation was critical in addressing the identification of abscess and cellulitis using ultrasound (4.57 ± 0.62). The simulation was critical in addressing abscess I&D (4.56 ± 0.66). These are indicated in Table 2.

Teaching quality received the highest overall domain score at 4.64 ± 0.52, indicating strong satisfaction with instructional aspects. According to Table 2, instructor(s) conveyed the material in a way that was understandable (4.77 ± 0.43). Instructor(s) were knowledgeable about the topic (4.75 ± 0.44). Learning materials improved understanding of the procedure (4.46 ± 0.90). Resources used during the session improved understanding (4.57 ± 0.74). The consistency across items reflects a high degree of confidence in the instructional delivery and supporting materials.

Comparative analysis by residency year (Table 3) revealed a statistically significant difference in self-efficacy scores (p = 0.012). Third-year residents had the lowest mean self-efficacy score (4.21 ± 0.53). While the first- and second-year residents reported higher self-efficacy (4.58 ± 0.50 and 4.79 ± 0.38, respectively). No statistically significant differences were observed across training years in the fidelity (p = 0.334), educational value (p = 0.337) or teaching quality (p = 0.486) domains.

| Domain | First year (n = 68) | Second year (n = 13) | Third year (n = 18) | Fourth year (n = 8) | F-value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-efficacy | 4.58 ± 0.50 | 4.79 ± 0.38 | 4.21 ± 0.53 | 4.56 ± 0.61 | 3.842 | 0.012* |

| Fidelity | 4.54 ± 0.53 | 4.79 ± 0.41 | 4.54 ± 0.42 | 4.72 ± 0.39 | 1.147 | 0.334 |

| Educational value | 4.62 ± 0.50 | 4.73 ± 0.40 | 4.42 ± 0.51 | 4.63 ± 0.63 | 1.138 | 0.337 |

| Teaching quality | 4.61 ± 0.56 | 4.81 ± 0.37 | 4.54 ± 0.51 | 4.75 ± 0.44 | 0.82 | 0.486 |

Note: Values represent the mean ± SD. The p-value is calculated by a one-way ANOVA test.

Survey responses were also compared based on participants’ prior experience performing I&D procedures (Table 4). Across all four domains, no statistically significant differences were identified (p > 0.05 for all comparisons), Self-efficacy (p = 0.184), Fidelity (p = 0.243), Educational value (p = 0.093) and Teaching quality (p = 0.145). These findings suggest that participant perceptions were not significantly influenced by prior clinical exposure to I&D procedures.

| Domain | 0 (n = 23) | 1 (n = 45) | 2 (n = 12) | 3 (n = 11) | >3 (n = 16) | F-value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-efficacy | 4.53 ± 0.49 | 4.53 ± 0.55 | 4.83 ± 0.29 | 4.59 ± 0.34 | 4.34 ± 0.65 | 1.584 | 0.184 |

| Fidelity | 4.68 ± 0.43 | 4.47 ± 0.56 | 4.79 ± 0.33 | 4.59 ± 0.53 | 4.61 ± 0.42 | 1.388 | 0.243 |

| Educational value | 4.73 ± 0.43 | 4.58 ± 0.49 | 4.83 ± 0.34 | 4.39 ± 0.53 | 4.44 ± 0.62 | 2.049 | 0.093 |

| Teaching quality | 4.67 ± 0.44 | 4.64 ± 0.47 | 4.92 ± 0.12 | 4.57 ± 0.54 | 4.41 ± 0.83 | 1.751 | 0.145 |

Simulation-based training has become a cornerstone of procedural education in emergency medicine. In emergency medicine, there is a high influx of unpredictable cases, which require high-acuity presentations. Prior studies have demonstrated its effectiveness in improving knowledge, procedural confidence and clinical performance [19–21]. In this study, residents reported high levels of satisfaction across all four MiSSES domains, including self-efficacy, fidelity, educational value and teaching quality, following a training session utilizing a low-cost and ultrasound-compatible abscess simulation model.

The results are consistent with the literature supporting simulation for I&D skill development. For example, Zendejas et al. [22] reported that learners trained using simulators outperformed those trained via traditional methods. Similarly, Morgan et al. [23] emphasized that simulation realism enhances learner engagement and procedural accuracy. The high-fidelity ratings in our study, particularly regarding the ultrasound visibility of abscess structures, suggest that even low-resource models can meet learner expectations when thoughtfully designed.

One notable observation was the variation in self-efficacy scores across training years (see Table 3). Third-year residents scored significantly lower in self-efficacy compared to first- and second-year residents. This trend may reflect increased clinical awareness or self-evaluation as residents’ progress through training. It is possible that third-year trainees become more attuned to their limitations and responsibilities, which results in a dip in their perceived competence. This phenomenon aligns with educational theories like the Dunning–Kruger effect, which describes decreased confidence as learners gain experience and recognize the complexity of their tasks [24]. These insights suggest that simulation may serve different purposes at different stages of training, for instance, confidence building in early years and skills refinement in later years. Additionally, this simulation model may have potential utility in training for minor surgical procedures such as lipoma removal owing to the similarity in incision techniques and tissue-handling skills.

Interestingly, prior I&D experience did not significantly influence MiSSES scores (see Table 4), indicating that the simulation was perceived as valuable regardless of baseline exposure. This finding aligns with the idea that simulation can offer consistent educational benefits across learner levels, reinforcing its utility for both novices and experienced trainees [25]. Future iterations of the model could also incorporate features for practising wound packing or closure techniques, which are important adjuncts in abscess management. Additionally, integrating this model into a hybrid simulation setup with standardized patients may enhance training in procedural communication and patient interaction.

This study did not explicitly incorporate a health equity lens in its design. However, the model’s accessibility and low production cost offer potential for broader use in under-resourced settings. The model lowers the barrier to entry for simulation-based training by using commonly available and inexpensive materials. Nevertheless, future iterations should consider equitable access in terms of language, cultural representation in materials, and delivery across training sites with variable resources. The generalizability of our findings may also be limited by the regional nature of the study. Expanding the evaluation to other healthcare systems and involving a more diverse participant population would enhance external validity and address equity-related gaps in training and dissemination.

There are four limitations in this research, which curbs the generalizability to a diverse population. First, although the calculated sample size was 168, only 107 residents completed the study, which may limit statistical power and representativeness. Recruitment depended on residents’ attendance at simulation workshops varied across centres. Second, while the model received high-fidelity ratings, were based mostly on junior residents’ perception, which may not fully capture model realism from an expert perspective. Third, the study relied solely on subjective feedback via the MiSSES survey and did not include objective performance assessments. Fourth, no follow-up assessments were performed to evaluate skill retention or clinical transferability. Lastly, although the model was designed to be low-cost, this study did not conduct a formal cost analysis or compare its educational effectiveness to other models.

This study evaluated emergency medicine residents’ perceptions of a newly developed, low-cost simulation model for abscess identification and drainage using the MiSSES survey tool. Participants rated the model highly across all measured domains. Findings suggest that the developed model offers a valuable educational experience for building procedural knowledge and confidence. Although variations in self-efficacy were observed by training year, overall scores remained consistently high regardless of prior clinical experience. This model represents a feasible addition to emergency medicine simulation curricula by combining ultrasound-compatible realism with affordable construction, particularly in settings where commercial models are not accessible. Further research should explore long-term outcomes, skill retention, and objective performance metrics. Integrating a health equity lens and broader multicentre validation will be essential to ensure simulation-based education serves diverse learner populations effectively.

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.