This essay builds on a previous editorial in which we posited that psychological safety is not something a simulation-based educator can ‘create’ or ‘ensure’ alone; that psychological safety is a relational concept. While simulation-based education often has critical technical elements, it has also been described as essentially a social practice. In this essay, we explore how micro-communication skills can contribute to shaping this social practice, and how simulation educators can use these practices to foster psychological safety and optimize learning. We argue for the use of micro-communication skills by simulation educators to shift from that notion of faculty ‘creating’ psychological safety to a position of ‘co-creating’ psychological safety with learners through mutual, responsive interactions. We propose how the social dynamic can be influenced through phatic communication, emotional pace setting, humour, physical/gestural communication, empathic communication, conversational pauses and turn-taking. By foregrounding the social dimensions of simulation-based education, we highlight how everyday communication choices shape learners’ experience, trust and growth.

What this essay adds

•Simulation-based education is embedded within a rich social fabric, where a myriad of social dynamics play out – some explicit, many implicit. Micro-communication skills can support educators and learners in navigating these complex social relationships. These skills can help learners manage the tension between being challenged and being supported in simulation-based education. When learners feel both stretched and safe, they are more likely to take risks and engage courageously in the learning process.

•While simulation-based education benefits from structured frameworks for pre-briefing and debriefing, micro-communication skills emphasize how we communicate, rather than just what we say.

•Given that psychological safety is a relational concept, these micro-communication skills can support simulation educators in fostering a psychologically safe space in simulation, realizing that as simulation educators, we can’t ensure psychological safety on our own. We argue that these skills can potentially lead to a state of ‘co-creation’ of psychological safety between simulation educators and learners.

Psychological safety is a prerequisite for effective learning [1,2]. Nowhere is this more pertinent than in experiential learning – whether in the clinical workplace or within simulated environments. Simulation educators often use scenario-based activities to create powerful learning moments. These may involve challenging subject matter (e.g. cardiac arrest, mental health crises, difficult conversations), as we stretch learners to the edge of their capabilities [3,4]. Moreover, learners are frequently asked to perform in front of their peers and instructors – circumstances that can heighten stress, evoke strong emotions and amplify their sense of vulnerability [5,6]. Whilst many learners may feel psychologically safe in a simulation activity, evidence suggests that some learners may default to concealing their true feelings and avoid expressing how they genuinely feel [5]. Outwardly, they may appear ‘fine’, but inwardly, they may feel exposed and unsafe.

As simulation educators, we are pedagogically, morally and ethically obligated to care for our learners [7]. We must strike a delicate balance when facilitating learners in simulation. On one hand, we must allow learners to be extended beyond their current abilities and to experience a sense of responsibility greater than what they are accustomed to [8]. On the other hand, we must provide enough support to nurture and scaffold professional growth [3]. Moreover, no two learners are the same. Therefore, we must strive to attune tacitly to each individual (i.e. to adjust simulation experiences in the moment in response to learners’ progress and states) as they move beyond their comfort zones and to connect with them in meaningful ways [4]. This means offering support when needed, or intentionally holding back, to allow learners to grow through experience, experimentation, and, importantly, error. Core to this process is psychological safety [9,10]. (i.e. ‘sense of being able to show and employ oneself without fear of negative consequences to self-image, status or career’ [10]). As simulation educators, we are at risk of creating conditions that feel ‘safe’ but lack the challenge needed for true development – a comfort zone that shields learners from failure rather than encouraging them to confront it. True psychological safety invites learners to be courageous; to take risks, make mistakes and grow from these experiences with the support they need. It is in this balanced space, where challenge is met with care, that optimal learning can occur [3,4].

In a previous article, we invited the simulation community to pause and reflect on the term psychological safety, a phrase often used, but not always fully embodied or felt in practice [11]. Simulation-based education has a social dimension, and so does psychological safety [10,12,13]. In this essay, we aim to continue this conversation by exploring one of the most important ‘tools’ in the social practice of simulation: how we communicate with each other. Specifically, we will consider micro-communication skills [14–17] (i.e. communicative techniques that help individuals develop rapport and nurture mutual understanding) and how they can be applied to further cultivate psychological safety in simulation-based education. We will not explore pre-brief/debriefing frameworks or questioning techniques, as these have been well covered elsewhere in the literature. Instead, we focus on some of the subtleties of communication – because it’s not just what we say to others, but how we say it that helps us socially connect meaningfully with others. For many simulation educators, these skills may be familiar as they are core to person-centred relationships (e.g. nurse–patient, doctor–patient etc.).

Learning can be viewed from many theoretical vantage points. In the context of simulation-based education, learning often occurs in the presence of others. Whether using a full-body humanoid manikin or working with simulated participants (SPs), learners typically engage with both peers and educators. When multiple individuals are present, social interactions inevitably arise in various forms. A rich theoretical grounding supports the notion that harnessing these social dynamics can promote the conditions necessary for effective learning [18–20]. Moreover, psychological safety does not reside solely within the individual – it is relational and often a group phenomenon [21,22]. By intentionally attending to social dynamics, we have the potential to foster environments where individuals feel supported to be open, take risks and not fear retribution when they make mistakes [21,22].

Technology has the potential to dominate our focus in simulation practice – the so-called ‘lure of technological’ [23]. While technology can enable learning, it should not overshadow other important dynamics within simulation-based education, such as pedagogy and the social aspects of learning. Simulation-based education has a deeply embedded social fabric, where a myriad of social dynamics play out and unfold – some explicit, but many implicit. From interactions between learners and their peers, to performing in front of simulation educators while striving to uphold professional credibility, to the relational dynamics within the pre-brief and debrief – these social elements can shape the learning experience. By promoting positive social interactions in simulation, we have the opportunity to enhance social cohesion, foster a shared sense of purpose, and cultivate relational dynamics that enable learning and psychological safety to thrive [10,12,13,18–20].

Social interactions are complex, fluid and constantly evolving. One of the most important ‘tools’ that enable effective social interaction is communication. Our field has made great strides in developing frameworks that guide what we say to each other – for example, debriefing frameworks that offer simulation educators a scaffold for navigating post-simulation discussions. However, while most frameworks focus on what we say, it is equally important to consider how we communicate with each other. Micro-communication skill practices refer to a range of specific behaviours and techniques that can be used in everyday interpersonal communication to improve rapport, empathy and social cohesion [14–17]. These practices have gained much attention in various arenas such as counselling and negotiation [24,25]. They have also been explored in clinical settings, such as consultations, where they can be used to enhance therapeutic relationships between healthcare practitioners and patients [26–28].

In the seminal work of Canadian sociologist Erving Goffman, he explored how individuals present themselves in social interactions to create a particular impression [29]. More than just the content of speech (i.e. ‘overt speech acts’), others assess sincerity and integrity through the way messages are conveyed – what Goffman referred to as ‘expressive behaviours’ or ‘ungovernable acts’ [29]. A disconnect between what is said and how it is said can create a perception of insincerity or distrust – critical factors that can influence psychological safety [10,21]. We propose that micro-communication skills have value beyond clinical care relationships: they can support learners in navigating the tension between being challenged and being supported in simulation-based education. When learners feel both stretched and safe, they are more likely to take risks and engage courageously in the learning process [3,5,10,21]. Moreover, such communication skill practices have the potential to convey that we hold learners in high regard and that they are genuinely valued in their learning, in addition to exchanging information [10,21].

What follows in this essay are conceptual examples of how micro-communication skill practices can be applied in simulation-based education, addressing the challenge of how we communicate and connect with others to co-create psychologically safe environments where learning can be allowed to flourish. More than ‘just words’ that we say, we recognize that many other dimensions contribute to effective communication. In the work of Albert Mehrabian’s, he proposed the ‘7-38-55’ rule of communication with respect to conveying emotion and meaning: only 7% of meaning is derived from the spoken words, 38% from paralanguage (e.g. tone, pace, intonation) and 55% through body language [30]. While we may not adhere rigidly to these proportions, it serves as a valuable reminder that communication extends well beyond the words we speak.

The kindly word, the cheerful greeting, the sympathetic look, trivial though they may seem, help to brighten the paths of the poor sufferers and are often as ‘oil and wine’ to the bruised spirits entrusted to our care (William Osler) [31]

We argue that as simulation educators, psychological safety is best co-created throughout the entire educational experience, and not, for example, left solely to the debrief [11]. Even before a pre-brief begins, there are meaningful opportunities to socially connect with learners and begin nurturing rapport and trust. Have you ever felt slightly rushed at the beginning of a simulation session – scrambling to make final adjustments while your students wait for the session to begin? This hurriedness can unintentionally transmit a sense of unease. In psychology, first impressions refer to the immediate and often unconscious judgements people make upon meeting someone for the first time [32,33]. Though brief, these initial interactions can have a lasting impact. From the outset – even a moment of welcoming learners into the simulation setting – educators are presented with a crucial opportunity to begin building rapport. ‘Emotional contagion’, a psychological phenomenon in which individuals unconsciously mimic the emotions of others [34,35], can play an important role here. If an educator appears flustered or distracted, these emotions can ‘spread’ to learners, potentially hindering the development of a psychologically safe learning environment. In contrast, welcoming learners with warmth and presence can help establish trust and signal that their learning experience matters. As educators, we have the opportunity to become positive emotional pacesetters for the group, setting a conducive emotional tone for the session.

Think back to a time when, while waiting for a session to formally begin, an educator engaged you in casual conversation. Similar to how a general practitioner might chat about the weather while walking a patient to the consultation room, these informal moments offer valuable opportunities to build rapport. This kind of light, non-task-focused interaction is known as phatic communication, that is, language used for social bonding rather than conveying substantive information [36,37]. Phatic exchanges, or ‘chit-chat’, can help establish a conversational rhythm, facilitate turn-taking and signal mutual respect [36,37]. These subtle social cues can make learners feel welcomed and recognized as individuals. Beyond warmth, these micro-communication skills help to foster an inclusive environment in which learners are more likely to engage openly and constructively.

Lastly, have you ever told a joke or made a light-hearted comment at the start of a simulation session? While humour carries some risk, particularly if misjudged, appropriate, inclusive humour can also play a powerful role in reducing social tension, signalling approachability, fostering a sense of group identity and encouraging openness [38,39]. What is your best light-hearted comment that you have opened a simulation-based learning exercise?

Beyond verbal communication, our bodies can serve as powerful tools to convey empathy and build social connections with others. Through physical and gestural cues, we can communicate presence, attentiveness and emotional understanding – foundations of psychological safety and trust [30,40,41,42]. Whether through facial expressions, posture, gestures, eye contact, or the use of proxemics (i.e. the use of personal space in communication and social interactions), we can enhance empathy by recognizing and responding to others’ feelings and emotions [30,41,42]. For example, if a simulation educator picks up on subtle cues that a learner is feeling anxious after a simulation, they can respond with physical empathy by offering steady eye contact, softening their facial expression, and perhaps adjusting their height to be at a similar eye level with the learner – thus reducing the perception of hierarchy that may come from standing above them.

Similarly, when a learner is debriefing their actions and shows signs of nervousness, simulation educators can use behaviour to demonstrate active listening – such as gentle head nodding, mirroring some of the learner’s physical cues or leaning slightly forward to reduce interpersonal distance. Mirroring individuals’ expressions, gestures and postures can help others feel seen, understood and supported – key components in building psychological safety [41–43]. Added utterances like ‘mm-hmm’ can further convey attentiveness and validate the learner’s experience. Moreover, when a learner performs well and displays visible joy or pride, simulation educators can reflect this with affirming gestures, such as a smile or a culturally relevant light-hearted fist bump. These responses reinforce connection and mutual recognition.

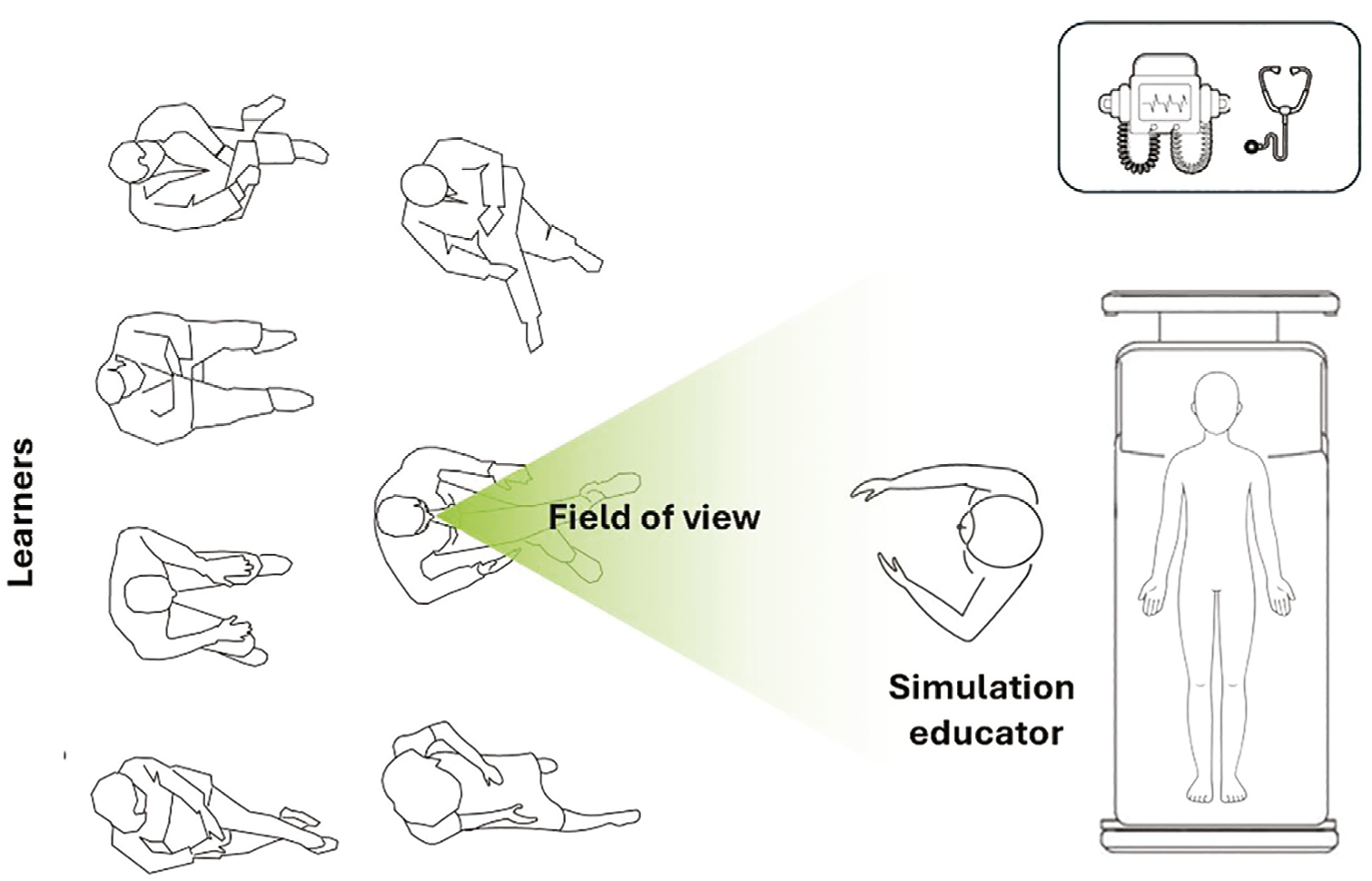

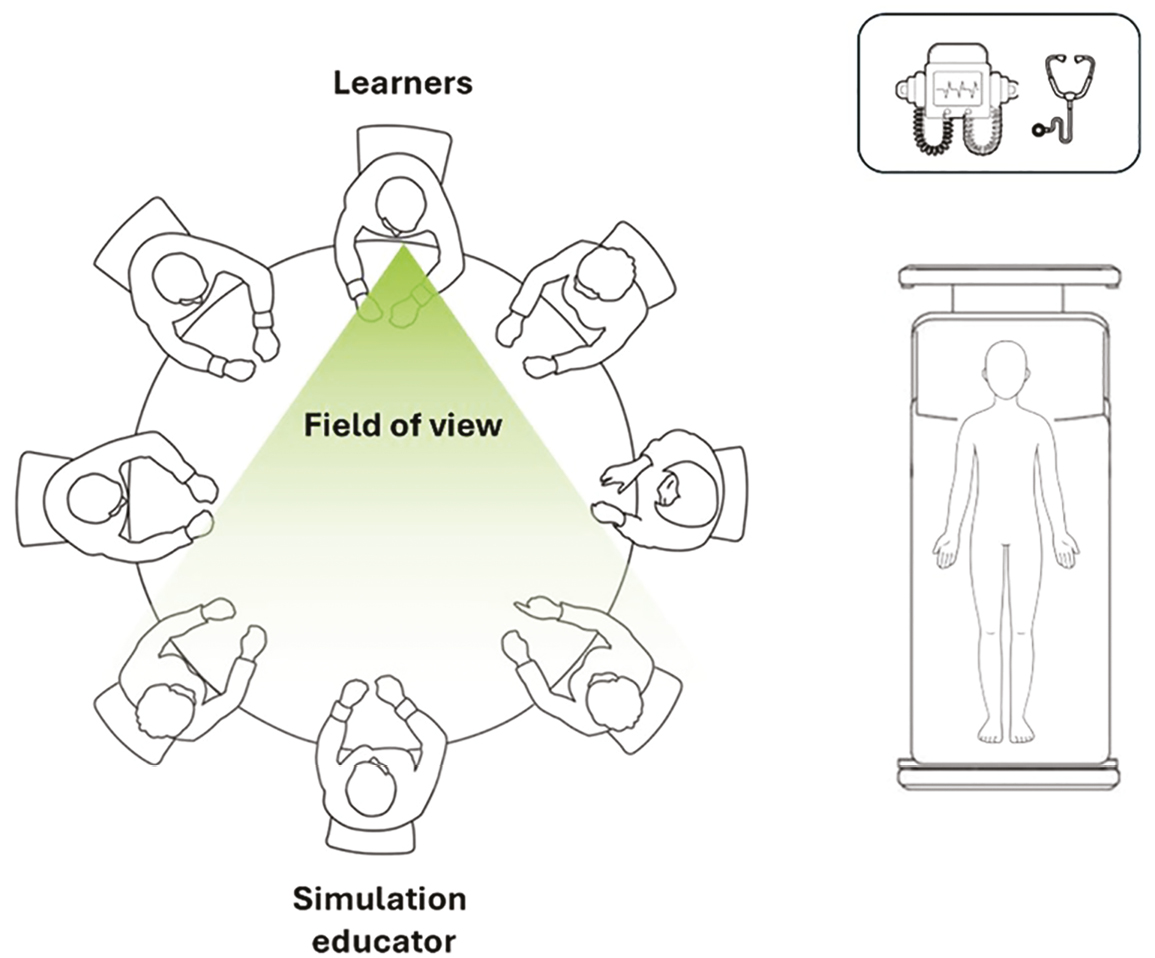

Importantly, all learners should be aware of and attuned to physical interactions as a means of enhancing trust and openness within the group. Where possible, learners should be physically positioned to observe and engage with one another – such as sitting in a circle (‘in the round’) rather than in rows during a simulation debrief – to support this dynamic (see Figures 1 and 2). This can also reduce power gradients (as opposed to a simulation educator standing in front of rows of learners) and enhance both connection and audibility. While we understand that space is often restricted in simulations settings to do this but that we should aim to make adjustments where possible.

Illustration of a theoretical seating arrangement in a simulation setting. In this configuration, learners are positioned in a way that limits their ability to observe one another’s physical and gestural reactions.

Illustration of an ‘in-the-round’ seating arrangement in a simulation setting. In this configuration, learners are positioned to more easily observe each other’s physical and gestural reactions, enhance audibility, and reduce potential power gradients between learners and the simulation educator.

Simulation can be an emotive method of learning [5]. Therefore, it is important that we acknowledge and work with learners’ emotions during the simulation learning process. Being aware of, open to and appropriately responding to others’ emotions can help to build rapport and trust [44,45]. Empathy is the ability to understand and share the feelings, thoughts and experiences of another person [46,47]. Empathic communication practices are one way to increase social bonding between individuals [46–48]. When we are empathic with one another, we demonstrate our capacity to connect emotionally [46–48]. Developing emotional resonance and imagining what it is like to be in someone else’s situation are cornerstones of empathic interactions. In the context of simulation, communicating empathy with learners can help them to begin to regulate their emotions and build trust – thereby allowing learning to occur in a psychologically safe manner. This can be conveyed through empathic phrases such as:

We have finished the simulation, and I can imagine that was a challenge, perhaps even stressful for you. You are not alone. Others often feel the same way … We’ll use this experience to further build on your skills moving forward.

The simple act of acknowledging and labelling emotions can be one of the first steps in supporting emotional regulation [49].

More than spoken words alone, we can also express empathy through paralanguage and physical and gestural communication. By attending to verbal tone, body language, facial expression and posture, we can help learners to feel seen, supported and understood. Mirroring a learner’s emotional cues can help convey that we recognize and value their perspective. For example, if a student appears challenged and displays signs of anxiety – such as a tense facial expression, a tilted head and leaning forward – mirroring these cues can help to signal to the learner that their emotional experience is being acknowledged and considered by you. Conversely, when a learner performs well and displays pride or joy, matching their cues with open posture and warm expressions can help validate and celebrate their experience.

We must also recognize that some learners may hide their emotional states. For this reason, it is important to conduct ‘temperature checks’ during the simulation, especially during debriefing. In clinical practice, a common micro-communication skill is to check in with a patient by asking how the consultation is going, giving the patient an opportunity to contribute and shape the interaction [50,51]. Similarly, educators in simulation can incorporate empathic check-ins with learners to assess how the learning experience is progressing. For example:

Can we take a moment to see how the learning exercise is going for you? Are we moving in a direction that feels beneficial to you?

Naturally, these interactions require appropriate timing and should be supported by empathic tone and physical communication practices.

The ebb and flow of conversation and social interactions during simulation unfold over time. The timing of when we speak, when we pause and the tempo of our communication all have the potential to foster mutual respect and enhance psychological safety in interpersonal exchanges [52,53]. As discussed previously, turn-taking in social interactions demonstrates reciprocity and shared understanding [36,37]. Co-creating a rhythm in conversation can help establish mutual respect and help to foster a psychologically safe space. Similar to patient consultations, we should aim to avoid interrupting others – particularly in the early moments of an interaction (the ‘Golden 2 minutes’) [50,54] – so as not to disrupt their expression or sense of agency.

That said, conversational interruptions and unexpected emotional disclosures do happen in simulation settings. For example, during the early phase of a simulation debrief – while a simulation educator is attempting to set the scene – a learner may suddenly exclaim:

That was awful. I completely messed up. I should have acted more quickly and intervened.

This comment clearly matters to the individual, and dismissing it could contribute to them feeling unheard, ultimately missing an opportunity to create a space to explore such emotions. However, engaging with this intense concern too early in the debrief may set an uneasy tone or inhibit the learner’s ability to emotionally regulate before engaging in reflective discussion. In such moments, we can draw on the clinical practice of ‘triaging’ issues – acknowledging their importance while revisiting them at a more suitable time. For example:

Thank you for sharing that – I can see it clearly means a lot to you. I’d really like to explore this further in the debrief. Are you okay for us to pick this up later?

Using empathic triage language such as this has the potential to allow learners to feel acknowledged and supported, while also maintaining a structured and emotionally attuned flow to the debrief conversation. However, it must be acknowledged that if a learner is overwhelmed by their actions and with self-criticism, it is important for the simulation educator to emotionally ‘read the room’ and ask themselves, ‘What if this learner’s emotional discomfort prevents us from moving forward?’ In such cases, it may be best to allow the learner to express their concerns in the moment and collaboratively address them before continuing with the simulation debrief.

The deliberate use of pauses and silence can also serve as powerful tools for fostering understanding and empathy in social interactions. For example, when asking a learner about their emotional experience, giving them space to process before responding can help them access and share their authentic feelings – rather than rushing to say ‘I’m fine’ in an attempt to fill the conversational space. Likewise, when a learner asks how they might improve a skill, a moment of thoughtful pause, perhaps accompanied by a contemplative gesture, can convey that you are genuinely considering their question and striving to give a meaningful response.

Lastly, the pace of speech plays a crucial role in emotional co-regulation. A learner who is anxious may speak rapidly, which can escalate feelings of stress. Research suggests that maintaining a calm tone and steady speaking tempo can help others emotionally regulate, come down to your tone and contribute to a safer psychological space [55,56]. By doing so, we communicate presence, honesty, and value [55–57].

| Micro-communication skill | Description | Example as applied to simulation |

|---|---|---|

| Phatic communication | Language used for social bonding rather than conveying substantive information exchange. | As learners arrive to the simulation location – welcome them with general ‘chit chat’ such as ‘Really nice to see you. Did you have a nice lunch? We’re just waiting on others to arrive and we will get sta’ted shortly. Did you have far to come today?” |

| ‘Emotional-pace setting’ | Emotional contagion is a psychological phenomenon in which individuals unconsciously mimic the emotions of others. If the simulation educator sets a positive tone, there is potential for this to be shared and reflected in learners. | As learners arrive to the simulation setting, meet them with a smile and open body language. Offer help for them to settle in and expressing that you are looking forward to the learning activity. |

| Humour | Inclusive humour can play a powerful role in reducing social tension, signalling approachability, fostering a sense of group identity, and encouraging openness. | Appropriate use of light humour, such as welcoming students to a simulation centre, such as ‘I’m sure you’re a little anxious. I was the same at your stage … but that wasn’t yesterday!’ |

| Physical and gestural communication | Our bodies can serve as powerful tools to convey empathy and build social connections with others. Through physical cues such as facial expressions, posture, gestures and eye contact. | If a simulation educator picks up on subtle cues that a learner is feeling anxious after a simulation, they can respond with physical and gestural empathy by offering steady eye contact, softening their facial expression, and perhaps adjusting their height to be at eye level with the learner – thus reducing the perception of hierarchy that may come from standing or sitting above them. |

| Empathic communication | The ability to understand and share the feelings, thoughts, and experiences of another person. Developing emotional resonance and imagining what it is like to be in someone else’s situation are cornerstones of psychological safety. | Using the following statement at the beginning of a debriefing exercise following a simulation: ‘We have just finished the simulation, and I can imagine that was challenging for you, perhaps even stressful for you. We’ll use this experience to build your skills moving forward’. |

| Conversation pauses | The deliberate use of pauses and silence can also serve as powerful tools for fostering understanding and empathy in social interactions. | When a learner asks how they might improve a skill, a moment of thoughtful pause, perhaps accompanied by a contemplative gesture, and convey that you are genuinely considering their question and striving to provide a meaningful response. |

| Turn-taking | Turn-taking in social interactions demonstrates reciprocity and shared understanding. Co-creating a rhythm in conversation can help establish mutual respect and help to foster a psychologically safe learning space. | A balanced conversation between a learner and a facilitator during a simulation. There are no interruptions, and the conversation feels naturally balanced. Simulation educator: How did you feel the scenario went? Learner: I think it went okay overall, but I was a bit unsure when the patient’s breathing started to worsen. Simulation educator: That’s a helpful observation. I’m keen to know what made you feel uncertain at that moment. Learner: I wasn’t sure whether to increase the oxygen or call for help first. I hesitated in that moment. Simulation educator: I see. That’s a common dilemma and you’re not on your own. I’m curious to know what your priorities were in that situation. Learner: I wanted to make sure the patient was stable, but I also didn’t want to delay getting assistance. Simulation educator: Good. That shows you were thinking about both immediate care and escalation. |

| ‘Temperature check’ on learning activity | When a simulation educator invites the learner(s) to consider how they feel the session is going and consider adjust their approach based on the learner(s) response. | Simulation educator: ‘That is great. I wonder if we could pause for a moment and check in how things are going? Do you think this approach is working for you in your learning? I’m really keen to hear and very open to modifying what helps you’. |

| Tone of voice | A learner who is anxious may speak rapidly, which can escalate feelings of stress. Research suggests that maintaining a calm tone and steady speaking tempo can help others emotionally regulate, come down to your tone and contribute to a safer psychological space. | When a learner appears anxious - expressing non-verbal cues such as a perplexed facial expression, rapid speech, heightened tone of voice, and closed body language – a simulation Simulation educator may try to ease the learner by maintaining a calm tone, speaking at a slower pace, and leaning forward to show that they acknowledge the learner’s concerns and are supportive in helping reduce their anxiety. |

In conclusion, we hope this essay serves as a stimulus to reinforce effective communication practices in simulation, while also opening up new ways of thinking about how we can harness the power of communication to further enhance psychological safety. Only by nurturing a psychologically safe learning environment can we enable courageous and reflective conversations in simulation that are essential for deep and transformative learning. Like a skilled gardener with many tools to cultivate growth, simulation educators, too, have a wide array of tools available in their educational toolkit. Our hope is that this essay encourages simulation educators to recognize and explore the many micro-communication strategies available to them. Importantly, just as not all tools are used at once in a garden, effective facilitation involves selecting the right communication tools at the right time – based on the needs of the learners and the flow of the simulation experience. The insight and responsiveness of a skilled simulation educator lie in their ability to do just that: create personalized, psychologically safe learning spaces through intentional and empathic communication. Finally, we hope this work stimulates further discussion and research within the simulation community, inspiring new lines of inquiry into how micro-communication practices can be more fully understood, applied, and taught in simulation-based education.

Please see Table 1 for a summary list of micro-communication skills as applied to simulation.

None declared.

None declared.

None declared.

None declared.

None declared.

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

30.

31.

32.

33.

34.

35.

36.

37.

38.

39.

40.

41.

42.

43.

44.

45.

46.

47.

48.

49.

50.

51.

52.

53.

54.

55.

56.

57.