Simulation-based education (SBE) is widely adopted in undergraduate nurse and midwife education. The extent, format and evidence for its use in nurse and midwife advanced practitioner education is under explored. The aim of this scoping review was to establish the extent and types of available evidence on SBE for nurse and midwife advanced practitioner education.

The Joanna Briggs Institute guidance for conducting scoping reviews was followed. The inclusion criteria were advanced nurse/midwife practitioner student learners exposed to SBE in their programme of education. The databases Embase (Elsevier), Medline (EBSCO), CINAHL (EBSCO), PsycINFO (EBSCO), Web of Science, Applied Social Science Index and Abstracts (Proquest), ERIC (Proquest) and Cochrane CENTRAL were searched from date of inception to April 2024. Google Scholar and ProQuest Dissertation and Theses was search for unpublished literature. The findings are summarized narratively, supplemented by graphs and tables.

One hundred and forty-six records, involving 5077 student participants were included in this scoping review. Records included 137 primary research studies that, respectively, were quantitative (76%), qualitative (10%) and mixed methods studies (7%). Eight records were reports of evidence syntheses (8%). These included four systematic, two integrative and two scoping reviews. The final record was a national SBE guideline for advanced practitioner education. Most records were from the United States of America (USA) and 48.6% were published in the 3 years spanning the outbreak of COVID-19. The description of the format of SBE, curriculum content and assessment and the reporting of simulation best practice standards reflect the presented findings.

The extent and use of SBE in programmes at the advanced practitioner level in nursing and midwifery is under explored in countries outside of the USA. As no literature was found in relation to advanced midwifery practice, this scoping review findings relate to advanced nursing practice. Improved reporting on the standards of best practice is needed in nursing research on SBE. The research methodologies were largely limited to quantitative research designs. Future research, which focuses on advanced midwifery practice and use of other research methods, would strengthen the knowledge base and our understanding of SBE in advanced practitioner programmes.

What this scoping review adds

The extent of evidence on simulation-based education (SBE) in advanced nurse practitioner education arises mainly from studies conducted in the USA and is largely quantitative in design.

Research on midwifery, as a distinct profession of advanced practitioner, is lacking.

There is a need to improve the reporting on the standards of best practice in SBE.

There is a need to improve reporting of educational theory underpinning SBE.

The growth in teaching and learning strategies, adopting adult-centred pedagogy, has increased in healthcare education. Simulation-based education (SBE) is an adult-centred instructional methodology, aimed at building on a foundational knowledge base to create new knowledge through immersive and interactive learning environments [1]. In graduate nursing and midwifery education, the integration of SBE in education programmes varies across and within geographical regions, higher education institutes and postgraduate programmes. Acknowledging that different terms are used to describe people seeking health treatment, in different healthcare practices and settings [2] (e.g. service user, client, consumers of health or women in the maternity setting), for purposes of this review the term ‘patient’ will be used throughout. SBE, in healthcare education, seeks to replicate the exposure practitioners have in clinical encounters where patient assessment, interaction and nursing and midwifery holistic care can be delivered and reflected on in a safe environment without compromise to patient safety [3]. Advanced practitioners (AP) are expert nurses and midwives, who have additional education which enables them to work as autonomous and accountable practitioners in a particular field [4]. The International Congress of Nurses (ICN) states that these practitioners have authority and responsibility to integrate ‘clinical skills associated with nursing and medicine in order to assess, diagnose and mange patients’ [4, p.6]. The curriculum development, programme design and review of education of APs is aligned with state and country nursing and midwifery governing bodies’ standards of education and practice [5]. Furthermore, education oversight to discharge the responsibility of AP education accreditation may vary from central governing bodies, regional and national boards or agencies [5].

The establishment of the AP role is the professions recognition of the need to address the imbalance between healthcare demand and supply [6]. The healthcare achievements of nurses and midwives have been documented since the 19th century and the concept of autonomous care delivery by nurses and midwives was first reported in the 1960s [7,8]. Despite the international recognition and evidence of the impact of AP roles on patient experiences and patient-centred healthcare delivery, providing education for these roles is not without challenges [9,10]. For example, providing clinical education and clinical exposure in the practice environment can be challenging. Associated difficulties include staff shortages; service need priorities; the preceptors’ own overburdened workload preventing them from providing the time, expertise and guidance to students, and the lack of specific or physical health system learning opportunities [11,12]. These constraints become problematic for programme’s specific requirements, including the requirement to achieve the international minimum expectation of 500 hours of direct clinical exposure, within the programmes’ timeframe, in addition to adding to the student burden to capitalize on opportunistic learning in the practice setting [4]. This education challenge may be further exacerbated with direct patient clinical hours increased from 500 to 750 hours, as required in the United States of America (USA), reported in the American National Task Force on Quality Nurse Practitioner Education [13]. Other countries may have to replicate this benchmark as health dynamic evolve.

Nurse and midwife educators in higher education institutes need to explore diverse teaching and learning methodologies to support student learning to develop the knowledge, skills, competency and confidence as APs. The pandemic event of 2020 threatened the delivery of healthcare education derailing normal education practice. Despite this, healthcare educators quickly adjusted by implementing alternative and complimentary educational strategies, in particular e-learning, to continue to meet the learning needs of participants in a time of unprecedented public health concern [14]. Alternative educational strategies, such as SBE can assist by bridging the theory practice gap and provide learning and assessment across the cognitive, effect and psychomotor domains at AP level [13]. The evidence of flexibility in programme delivery reflects some of the positive changes initiated during the pandemic restrictions, when traditional face-to-face teaching, learning and assessment were not permitted or hindered [15]. Waxman et al.’s call for a ‘renewed focus on what occurs in the 21st century clinical setting, encouraging new reflection and evaluation of this heretofore “gold standard” of clinical education’ [16, p.301] was thus set in motion as willingness to engage in other forms of clinical education began. Nonetheless, governing bodies that oversee nursing and midwifery education standards must be satisfied with the quality and evidence to consider the change [17].

A survey by Nye et al. highlighted a variation in simulation hours, consensus on replacement of clinical hours with simulation, and the content taught in nurse and midwife practitioner programmes using SBE [18]. In addressing the variation in nurse practitioner (NP) programmes, the National Organisation of Nurse Practitioner Faculties (NONPF) emphasized the need for the standardisation of SBE in programmes to align with NP competencies and, thus, provide measurable educational opportunities to benchmark SBE against clinical practice experiences [12]. Further objectives of the national forum include the advancement of the science of SBE, as a teaching methodology, in AP programmes through quality research which included the reporting and implementation of simulation standards [12]. In addition, the NONPF SBE guideline provides key definitions that describe SBE. These definitions provide understanding and clarity of terms for SBE stakeholders. Lioce et al. updated published work, the healthcare simulation dictionary, provides evidence of the evolution of healthcare simulation terminology since its first edition in 2013 [19]. As terminology in the field of healthcare simulations evolves, it is important to capture key concepts or standardized terms that emerge in AP SBE research. For readers of research, it gives a reliable understanding of how SBE is conceptualized and defined internationally.

Clarity on the extent and use of SBE in Europe is reported with mixed results. Chabrera et al. compared the level of SBE implementation in the nursing curricula by consulting an expert panel gathered from higher level institutes across eight countries in Europe [20]. Findings from the exploratory study report that Eastern European countries (Poland, Croatia and Czech Republic) have embraced SBE as a teaching methodology in nursing programmes with consistent compulsory hours allocated to SBE in the curriculum at undergraduate level [20]. SBE studies at the graduate nurse/midwife programme level was not explored by the panel which suggest this discourse is lacking and needs to be discussed. One of the recommendations of the exploratory study, included a similar call for quality research to support greater implementation of SBE in the nursing curriculum.

To determine the appropriateness of conducting the review, we searched JBI Evidence Synthesis, PROSPERO and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews to establish the existence, or not, of reviews on the topic, either completed or in progress. We found two completed reviews and no ongoing reviews. One of these was a systematic review on the effectiveness of SBE on satisfaction and learning outcomes in NPs’ programmes [3], and the second was a scoping review of SBE in nursing practitioner programmes. This latter review was limited to studies conducted in America only, and the search strategy did not include a search of any educational databases [21]. As our planned scoping review was broader in scope, geographically and in populations which included midwives, we deemed the present review appropriate and needed. To foremost ascertain the extent of research on SBE in AP nursing and midwifery programmes, we undertook a scoping review with the following objectives:

1.Determine the extent of evidence on the use of SBE in nurse and midwife AP education programmes, including which countries are reporting research on SBE in AP education and the research approaches adopted.

2.Determine if SBE is defined in the identified AP studies, including existing similarities or variations in definitions for a reliable understanding of how SBE is conceptualized internationally.

3.Identify characteristics or standards of SBE in the identified studies, including what aspect(s) of AP is being taught using SBE, the learning theories/frameworks underpinning SBE and what are the learning outcomes associated with the SBE.

Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) methodological guidance for scoping reviews underpinned the conduct of this review [22,23]. The review protocol has been published [24]. The findings are presented both narratively and graphically as outlined in the protocol [24]. The review adheres to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) checklist [25] (Supplementary Appendix 1).

The eligibility of studies was guided by the population, concept and context (PCC) framework, recommended by JBI [23].

Studies involving nurses or midwives enrolled in programmes that lead to registration as an AP were eligible for inclusion. In enrolment into their programme, the student participants were exposed to SBE for teaching, learning or assessment. The definition of ‘advanced practitioner’ is as per the International Congress of Nursing [4].

The concept was any form of SBE, where the objective of the teaching methodology was to scaffold the teaching, learning and assessment of programme content at the AP level. These included for example simulated participant (SP), role play or high-fidelity simulators.

The context was SBE delivered in any format and setting, for example, the delivery of SBE could have taken place in the university, college, clinical practice setting or virtual spaces within an AP education programme.

This scoping review considered all primary research using quantitative, qualitative and mixed methods approaches. Evidence syntheses sources, including scoping reviews, integrative reviews and literature reviews on SBE in the population of interest were also eligible. In addition, grey literature was considered for inclusion from theses, dissertations and information produced by nursing and midwifery AP education bodies that referred to SBE at the AP student level. Editorial and opinion pieces or studies where the participants had already completed their education programme and were registered as APs were excluded.

To help develop and inform the search strategy, an initial limited search of Embase, Medline (EBSCO) and CINAHL (EBSCO) was undertaken by a subject librarian, using full and abbreviated terms related to AP, nurse or midwife practitioner, simulation and SBE. This search helped to identify relevant keywords and index terms for the formal search strategy. Once finalized, the search strategy, combining search terms related to the population and concept (see Supplementary Appendix 2), was implemented in eight databases, from date of inception, initially to January 2023, and then updated to April 2024. These were Embase (Elsevier), Medline (EBSCO), CINAHL (EBSCO), PsycINFO (EBSCO), Web of Science, Applied Social Science Index and Abstracts (Proquest), ERIC (Proquest) and Cochrane CENTRAL. Languages or other limits were not applied to the searches. Searches of other sources were also undertaken to supplement the database searches (Supplementary Appendix 2). To increase the sensitivity of the search a proximity operator was applied to the search terms advanced midwife/nurse practitioner (i.e. Near 2/wildcard*). This was designed to capture the variation of job roles and titles in this area. The selection of eligible records was limited to those published in English. No published records in other languages were identified. The findings of the searches were then added to Covidence for screening.

Records from all searches were uploaded to Endnote 20, (Endnote [2022], Philadelphia, PA Clarivate) where an initial deduplication was performed. The remaining records were then exported to Covidence (a software programme for the conduct of systematic reviews) where further deduplication occurred. Two independent reviewers (KMcT and PM) screened the Covidence records on title and abstract in accordance with the eligibility criteria and objectives of the scoping review. Screening and selection of the first 25 articles was piloted and discussed to ensure consensus between the reviewers. After screening on title and abstract the same two reviewers independently assessed the full text of the records forwarded from the title and abstract screening against the review’s eligibility criteria. Full text studied that did not meet the inclusion criteria were excluded.

Data were extracted from the included records by two independent reviewers (KMcT and PM). The data extraction tool (as per protocol) [24] was tested for adequacy and comprehensiveness by two reviewers independently piloting the tool on three studies. Adjustments to the tool were made to include the aim of the studies and whether a definition of simulation was explicit in the included records as well as charting the modality of simulation. Data extraction included details about the population, concept, context, in addition to details relating to the country, year, journal title, type of evidence source, study methods, reported standards of simulation best practice (if any), associated educational theory, content taught and the learning outcomes of SBE, whether SBE was used for formative, summative or both forms as an assessment strategy in programmes delivered to APs. Table 1 presents the data charting tool. Any discrepancies between the reviewers were successfully resolved through discussion.

| Scoping review details | |

|---|---|

| Person extracting the data | |

| Date data extracted | |

| Scoping review title | |

| Details and characteristics | |

| Citation details (e.g. author/s, date, title, journal, volume, issue, pages and doi) | |

| Country of origin | |

| Types of evidence source | |

| Aim/objective | |

| Population/description of the population | |

| Concept/simulation modality (standardized patient, high-fidelity simulator, virtual patient, telehealth standardized patient, role play and task trainer) | |

| Context (location of simulation activity) | |

| Definition of simulation (if provided) | |

| Standards of simulation reported INACSL | Professional development Prebriefing Simulation design Facilitation Debriefing process Operations Outcomes & Objectives Professional integrity Simulation enhanced IPE Evaluation of learning and performance |

| Curriculum content using SBE | |

| Learning outcomes (Summative/Formative) | |

| Theory reported | |

The data were summarized, and the review findings are presented narratively supported by figures, illustrative charts and tables as per prior protocol [24]. The findings are presented in three sections which address, directly, each of the reviews three objectives.

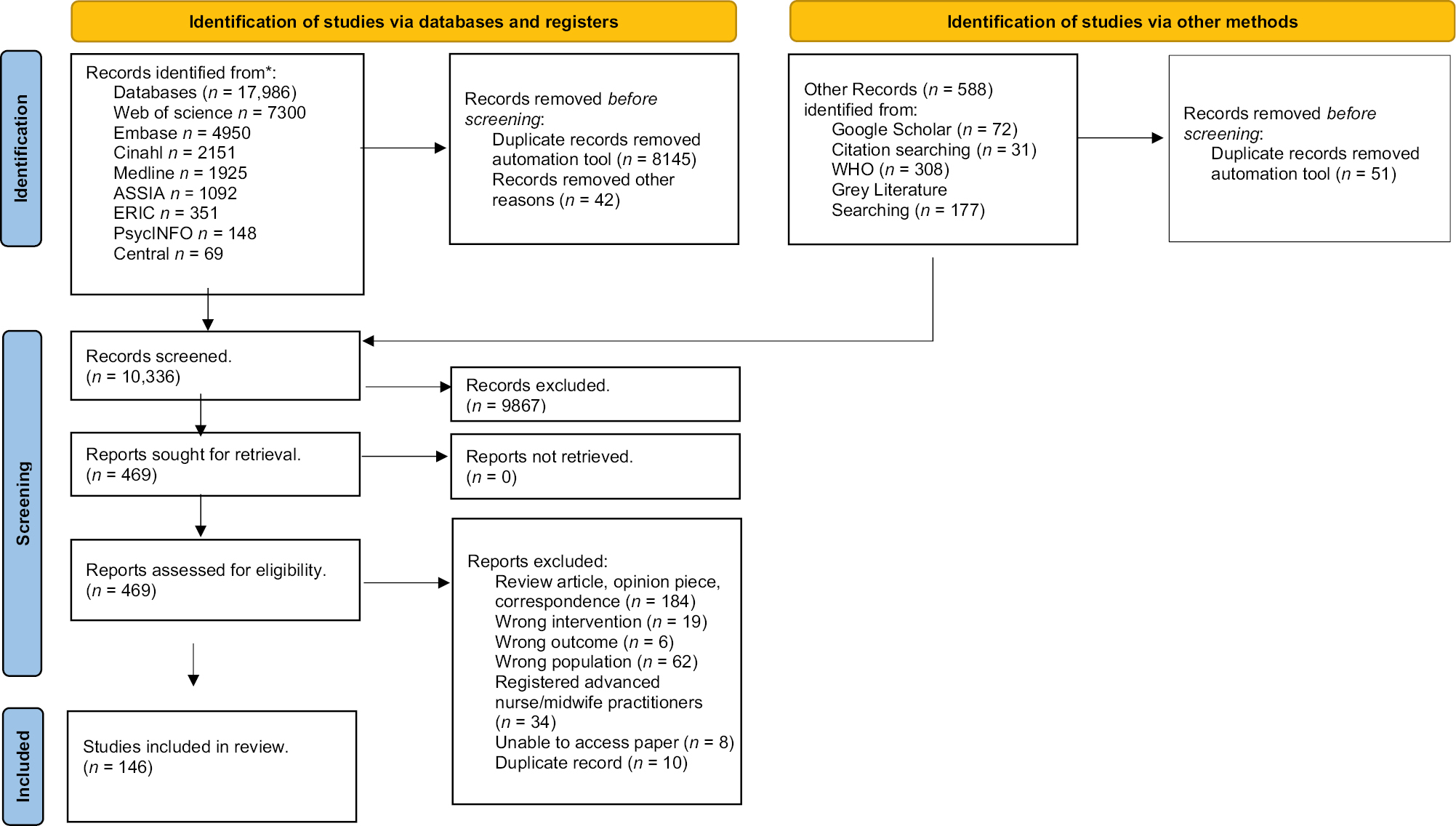

The database searches yielded 18,574 records of which 8196 were identified as duplicate and were removed. Following title and abstract screening of the remaining records, a further 9867 records excluded as these were clearly ineligible. Following full text review, 323 of the remaining 469 records were excluded, with reasons provided in Figure 1 (search and selection process). This resulted in the inclusion of 146 records in this scoping review [3,12,16,18,21,26–168]. The PRISMA diagram (Supplementary Appendix 1) provides an overview of the study selection process.

Search results, study selection and inclusion process

The characteristics of the included records are presented in Supplementary Appendices 3 and 4, and definitions of terms used in the records in Supplementary Appendix 5. In brief, the publication dates of the included records spanned from 1979 [28] to 2024 [29] with 72% (n = 107) published since 2016 (see Table 2). Notably, the number of published records during the years that WHO declared the COVID pandemic a global emergency (2020–2023) were respectively 16 records (22.5%) in 2020 [12,31,60,82,86,96,100,104,112,113,133,140,142,151,163,166], 24 records (33.8%) in 2021 [26,30,33,34,45,46,48,49,57,62,64,76,81,88,90,107,130,134,135,139,141,156,157,160], 24 records (33.8%) in 2022 [21,36,38,39,42,43,47,50,63,65,66,85,94,95,101,109,115,125,126,131,154,161,164,167,168] and 7 records (9.85%) in 2023 [58,80,103,108,137,146,158], totalling 71 records for the period, which is 48.6% of the total published work identified for this scoping review. The context for SBE was universities, virtual spaces, clinical settings and the community. SBE, as described in the included records, involved role play, SP interactions, telehealth with SP, SBE with high-fidelity simulators (HFS), virtual interactions and computer-based interactions. Of the 71 records published during the pandemic years, SBE with SP was reported most frequently (n = 22 records), followed by telehealth with SP (n = 22 records), virtual and computer-based interactions (n = 14 records) HFS (n = 4 records) and one record reported on the use of a task trainer. During this period, published work included the NONPF guidelines on SBE in AP education [12] and five evidence syntheses [21,164,166,167,168].

| Study characteristics | No. of studies (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Publication by year | ||

| 1979–1989 | 2 (1.5%) | |

| 1990–2000 | 2 (1.5%) | |

| 2001–2005 | 4 (3%) | |

| 2006–2010 | 10 (7%) | |

| 2011–2015 | 21 (14%) | |

| 2016–2020 | 46 (31%) | |

| 2021–2024 | 61(41%) | |

| Country of publication | ||

| United States of America | 138 | |

| Canada | 1 | |

| Brazil | 1 | |

| France | 1 | |

| Norway | 1 | |

| South Korea | 1 | |

| Singapore | 1 | |

| Thailand | 1 | |

| Taiwan | 1 | |

| Sample size primary studies | ||

| <25 participants | 65 (47%) | |

| 25–50 participants | 47 (35%) | |

| 50–100 participants | 22 (16%) | |

| 100–200 participants | 3 (2%) | |

| Setting | ||

| University (in person) | 95 (69%) | |

| University (Online Virtual) | 26 (19%) | |

| University (Hybrid in person & online university platform) | 11 (8.5%) | |

| University Blended (in person and clinical) | 1 (0.75%) | |

| Clinical | 3 (2%) | |

| Community | 1 (0.75%) | |

| Study design | ||

| Quantitative | 113 (76%) | |

| Qualitative | 14 (10%) | |

| Mixed methods | 10 (7%) | |

| Evidence Syntheses | Methods | 8 (6.25%) |

| Systematic review | 4 | |

| Scoping reviews | 2 | |

| Integrative review | 2 | |

| Educational guidelines | 1 (0.75%) | |

No records relating to the use of SBE in advanced midwifery practice education were identified in the search; thus, the findings of this scoping review relate to advance NP education.

In this scoping review 146 sources were identified where SBE was reported in any format and discussed in AP programmes. The records spanned nine countries and four continents, although most records were from the USA (n = 138), with the remaining eight records originating each from Canada [3], Taiwan [91], Singapore [149], Norway [153], South Korea [158], Thailand [164], Brazil [165] and France [168]. The types of evidence of the 146 records were 137 primary studies consisting of 113 quantitative [17,25,28–139], 14 qualitative [140–153] and ten mixed methods study designs [154–163]. Eight records were evidence syntheses, of which four were systematic reviews [3,27,164,168], two were integrative reviews [165,166] and two were scoping reviews [21,167]. The remaining record was an educational guideline on SBE in AP education programmes published by the NONPF [12]. The participant population were AP NPs’ students in 136 of the 137 primary studies with the remaining one study referencing participants as nurse–midwife practitioners [150]. The included studies comprised of 5077, AP participant student learners in the records. The number does not include IPL participants, for example, undergraduate nurses, medicine or pharmacy. The population sample varied in size in the primary study records, ranging from six [45] to 171 [34] (Table 2).

The population in the included records were from generic AP programmes (no population speciality provided) as well as population specific specialties, referred to as discipline specific AP track programmes. In the USA the term ‘track’ is used to describe the area of AP specialty. The term ‘NP’ is preferred to AP in the USA.

Twenty-nine studies also included the amalgamation of students from one or more speciality tracks [42,44,54,56,58,66,68,73,74,76,89,93,96,97,104,115,125,129,132,134,136,139,140,150,151,154,157,162]. In 12 studies the AP student population, as part of their programme, participated in simulation with interdisciplinary nursing grades [40,66,77,86,87,109,118,123,124,152,156,161] and, in 11 studies, with other healthcare professions. The interdisciplinary professions included medicine, pharmacy, dentistry, dietician, physical-therapy, social work and communication graduate students [55,57,59,67,72,102,110,133,144,155,163].

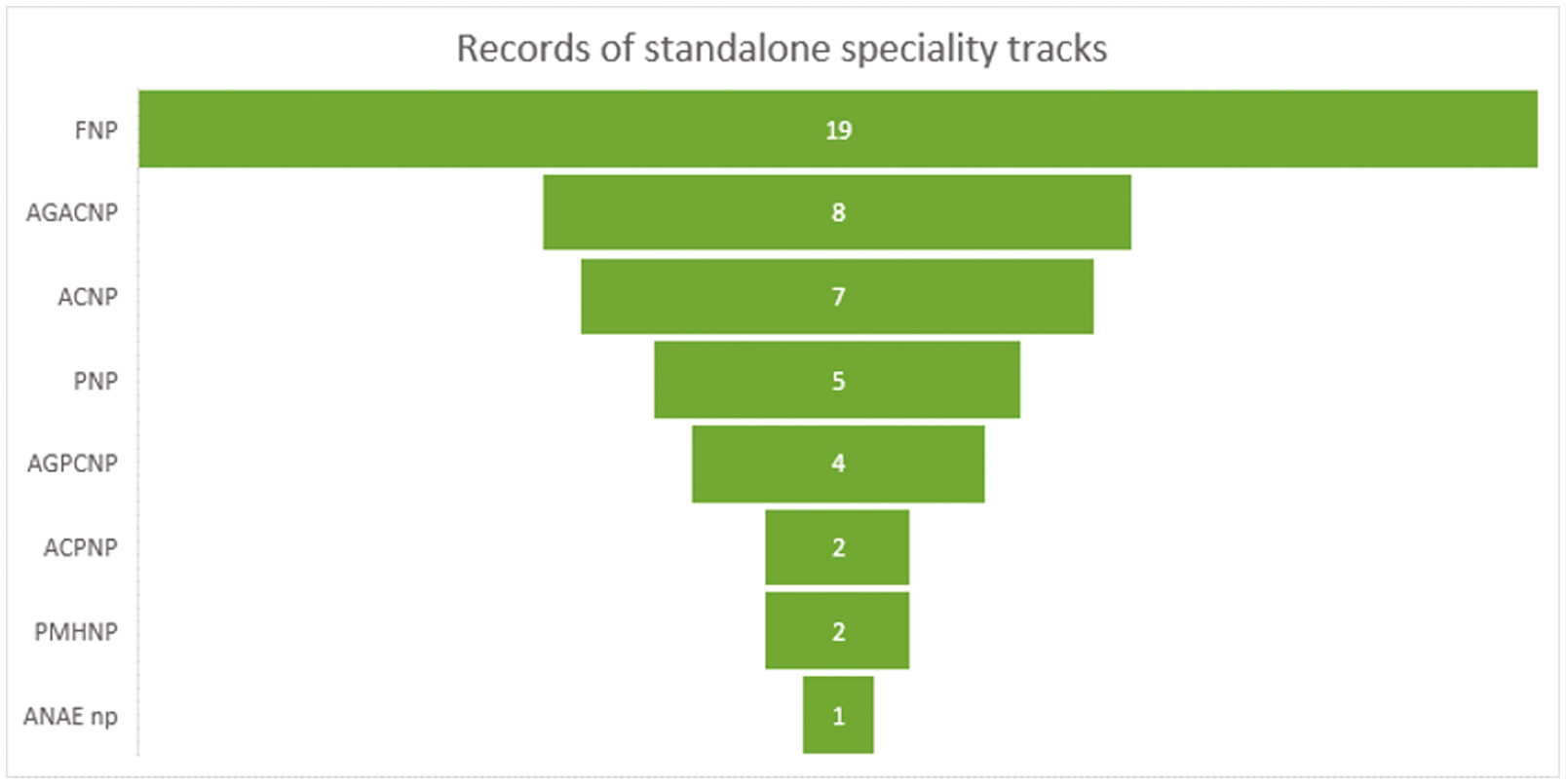

The speciality track reported most frequently as a standalone track was family nurse practitioners (FNP; n = 19) [28,30,34,38,39,47–49,52,78,80,94,100,111,121,122,127,135,147] followed by adult-gerontology acute care nurse practitioner (AGACNP; n = 8) [33,50,61,70,105,117,146,159], acute care nurse practitioners (ACNP; n = 7) [31,35,51,53,116,120,141], paediatric nurse practitioners (PNP; n = 5) [65,69,114,126,131], adult-gerontology primary care nurse practitioners (AGPCNP; n = 4) [26,45,90,103], acute care paediatric nurse practitioners (ACPNP; n = 2) [75,95], psychiatry mental health nurse practitioners (PMHNP; n = 2) [29,62] and anaesthetic nurse practitioners (n = 1) [148] (Figure 2).

SBE records identified by speciality in AP programmes

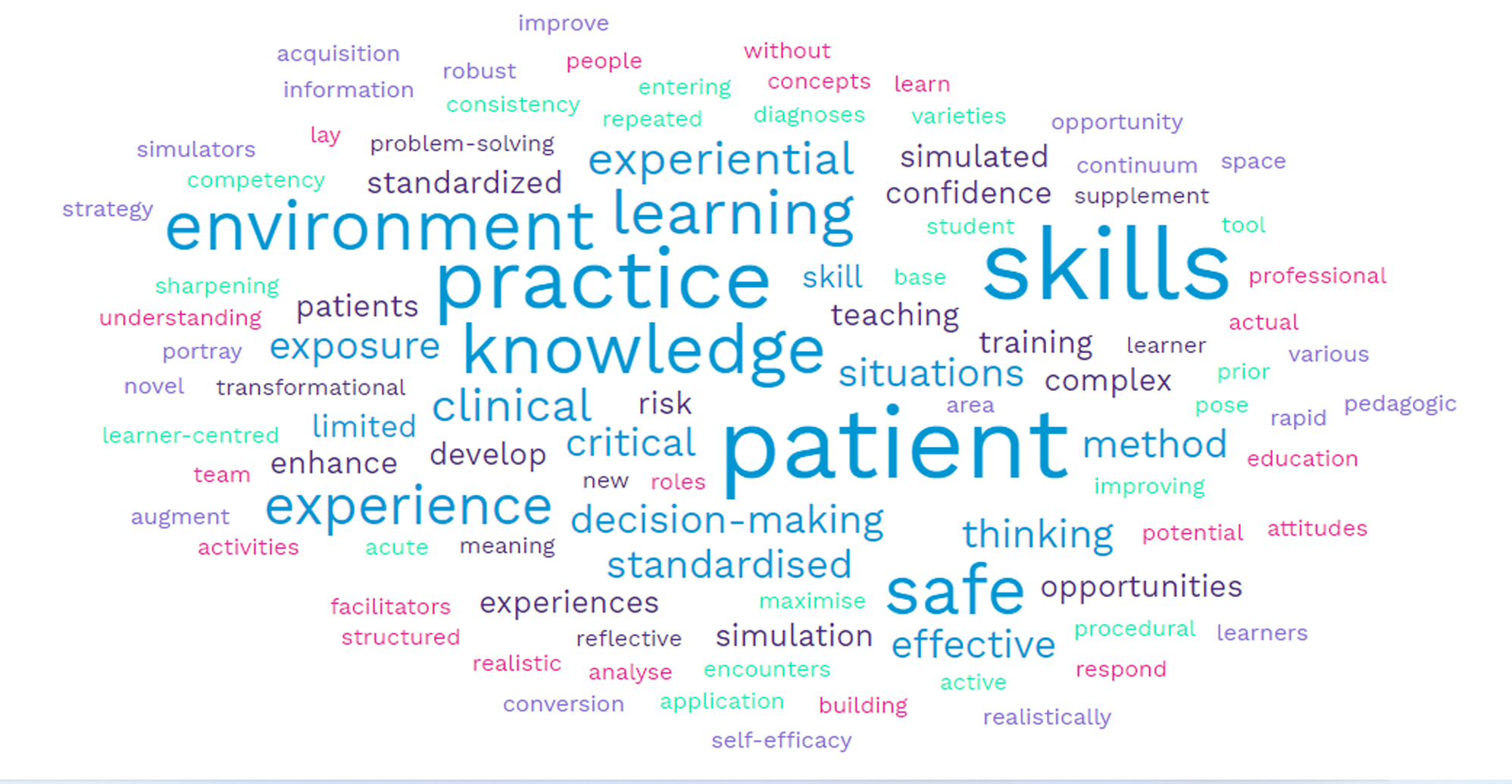

Sixty-four of 146 records described SBE without the provision of a definition of simulation within the articles main body. The 82 remaining records provided explicit definitions (Supplementary Appendix 5). Similarities across the terms are broadly grouped into (a) educational terms, (b) context conducive to SBE and (c) embedding cognitive growth (Figure 3). For example, education terms were grouped where language explicated ‘learning/teaching terms’ such as learning by doing, problem-based learning [45], experiential learning [54] and active learning experience [76]. Context conducive to SBE terms, for example, reference the importance of SBE safety: in safe true like setting [49], safe and controlled environment [53], controlled laboratory environment [73], safe environment [74], without risk [95]. Finally embedding cognitive growth terms, for example, included: independent critical thinking skills [99], problem solving and critical thinking skills [118], sharpening their critical thinking [120], enhance knowledge, skills and attitudes or to analyse and respond [125].

Summary of terms used to define simulation

Standards of SBE are a set of characteristics or indicators to communicate consistency in the development, implementation and review of SBE practices in healthcare education [169]. Examples of standards include the International Nurse Association for Clinical Simulation and Learning (INACSL) published standards from 2011 which were updated in 2021 [170], as well as Association for Simulation Practice in Healthcare standards (ASPiH), updated in 2023 [171]. These standards provide a framework for simulation in research and thus informs the evidence base for those adopting SBE in teaching and learning [170]. Nye et al. assert that these standards ‘strive to enhance the consistency of developing and implementing simulation in nursing programs’ [18, p.5]. Forty (27.3%) of the 146 included records explicitly reported the inclusion of the INACSL standards in the design, development and implementation of SBE in the research [18,30,31,33,38,43,44,47–50,54,58,64,67,79,82,88,90,94,95,104,107–109,117,122,124,129,134,135,138–140,146,149,154,156,159,161] and 16 records predated the INACSL/ASiPH standards of best practice [28,37,41,53,77,92,111,116,120,121,127,128,132,145,148,152]. None of the studies included in this review reported the adoption of the ASiPH standards of best practice. Of the included evidence syntheses none reported on simulation standards of best practice as an outcome of the syntheses. The guidance on simulation research is clear that standards must be reported otherwise it limits the advancement of science on simulation in healthcare [170,171].

In the AP curriculum, 60 included records described teaching, learning and assessment of the principals and practice of obtaining a health history, advanced physical health assessment, clinical decision-making, differential diagnosis and patient care planning in the SBE activity [26,31,32,34,36,38,39,41,42,43,45,48,50,51,52,53,56,60,64,67,68,70,71,75,77,79,82,84,87,90,95,102–104,105,107,108,109,112,114,119,122,123,125,127,131,134,135,137–139,144,145,147,149,150–153,156,159]. Other content included critical thinking and decision-making competencies as standalone learning outcomes (n = 18) [29,31,33,37,40,42,47,88,92,96,97,99,101,113,120,121,126,146], advanced practice of skills specific to the role on the AP (n = 16) [35,54,66,69,72–74,81,85,92,94,100,128,129,136,148], three records that focused on skills related to using information technology, electronic healthcare records and accessing research for real-time review and critique in practice during an SBE experience [49,78,80] and one record where the focus of SBE was advanced practice management/leadership [141]. Another prominent theme identified in the included records, particularly in the last 5 years, was the focus on advanced communications skills (n = 36) [30,46,51,55,57–59,61,62,65,76,83,86,89,91,93,98,106,110,111,115–118,124,130,133,143,155,157,158,160–163]. Topics include interprofessional communication, motivational interviewing, patient education, conflict resolution and breaking bad news. Sensitive issues included advanced care planning for end-of-life care, substance abuse/misuse, gender and sexuality conversations, interviewing competencies incorporating abuse such as child or adult sexual abuse and violence was the focus of the SBE experience. Other areas explored included weight-based conversations for obesity, behavioural and mental health interviewing techniques/counselling.

There was a range of adult learning theories and learning frameworks reported in 64 records. Eighteen different theories were identified, and ten frameworks or models adopted in SBE teaching and learning practices in the programmes (Table 3). The most popular learning theories include Kolb’s experiential learning theory (n = 16) [18,29,31,38,44,45,47,54,76,88,94,109,139,151,154,157], and the NLN Jeffries simulation theory (n = 9) [43,67,90,114,122,129,138,140,161] (Supplementary Appendix 3). Two evidence syntheses reported on learning theories/frameworks [21,162].

| Theory reported in primary studies | |

|---|---|

| Kolbs experiential learning theory | 16 |

| NLN Jeffries simulation theory | 9 |

| Ericsson theory of learning | 3 |

| Problem-based learning theory | 2 |

| Cognitive learning theory | 2 |

| Transfer of learning theory | 2 |

| Social learning theory | 2 |

| Situated cognition | 2 |

| Cognitive flexibility theory | 2 |

| Critical thinking theory | 1 |

| Millers theory | 1 |

| Self-efficacy theory | 1 |

| Deliberate practice theory | 1 |

| Ecological psychology perspective | 1 |

| Dual processing theory | 1 |

| Theory of engagement | 1 |

| Motivational interviewing theory | 1 |

| Humanistic philosophy of education | 1 |

| Frameworks | |

| Benners model | 2 |

| Finks model | 1 |

| Blooms taxonomy | 1 |

| COPA framework | 1 |

| IPE competencies | 1 |

| Team STEPPS framework | 1 |

| Roys adaptation model | 1 |

| Barracolough skills acquisition | 1 |

| NONPF simulation guideline | 1 |

| Daley and Campbell’s framework for simulation | 1 |

The use of SBE in AP programmes underpinned both formative and summative learning and assessment. Formative assessment refers to the cyclical processes to evaluate student progress during the programme for the purpose of improvement [172]. Formative assessment was identified in 102 records. Whereas summative assessment refers to the final means in which the learning outcomes of a programme are assessed [173]. This was identified in 29 records. SBE for both forms of assessment were identified in three primary studies [35,68,142], in one [167] evidence synthesis and in one guideline [12] (Supplementary Appendices 3 and 4).

Fourteen qualitative studies were included in this scoping review [140–153]. The focus was on simulation, to explore AP students’ experience of its use to support AP competencies. Despite the differences in the objectives or aim of the simulation (communication [140,143,144], health assessment [142,147,149–153], leadership, decision-making/diagnostic reasoning [141,145,145] and advanced procedural skills [148], all AP students reported that SBE identified new learning as they reflected on the challenges of their expanded scope of practice. The theme of exposure of the SBE experience in a safe environment underscored by debriefing after the interaction was identified positively for the AP student.

This scoping review identified the types and scope of studies on SBE in AP student education, albeit with respect to nursing only, as no records that focused on advanced midwifery practice were identified. The findings have relevance applicability for AP education broadly, however, and especially as the growth in AP roles expands in other healthcare professions [174]. As the delivery of healthcare becomes more complex and the student population becomes more diverse, healthcare education stakeholders will be required to consider flexible teaching and learning strategies that meet the needs of the healthcare workforce. APs are a cohort of the healthcare eco system that are motivated through continuous professional and personal development to navigate complex healthcare challenges. This scoping review highlights an increasing expansion of evidence on SBE to scaffold teaching and learning for AP education. The COVID-19 pandemic was a pivotal catalyst for transitional change from traditional teaching and learning methodologies to SBE, which occurred to ensure that disruption to education was minimal to enable continuing resourcing for AP roles [15,34,45]. The rise in literature on SBE, is evident from the records identified in the last 3 years, as a finding of the review. This surge is likely related to the challenges to AP education and the solution focused approaches implemented in an unprecedented time in healthcare [39,90]. Additionally, there is evidence of the continued strive to advance knowledge, skills and competencies, required for the autonomous AP role. This is in part due to the enforced changes at the time of the pandemic, notably the move to incorporate more e-health and technology as well as the strategic reflection on the complex and future healthcare needs of the population [14,15,90]. The response from educators is to integrate, through simulation design practices, SBE experiences into the curriculum of AP programmes in terms of providing a solid foundation for safe quality care delivery. Additionally, as the pace of change in healthcare accelerates, SBE provides a safe testing ground to reflect in and on AP delivery. This can offer students of AP programmes added confidence in their abilities and strengthens their scope of healthcare practice delivery [143,153]. This scoping review identified 14 qualitative studies which highlights the need for more research to explore AP student experiences and perceptions of SBE. Emphasis on the importance of debriefing from the student AP’s perspective was highlighted [140–153]. Four records [31,47,94,141] were found where debriefing as a standard of best practice, was explored as an aim or objective of AP SBE research.

The review also mapped the countries where research is conducted on SBE in relevant programmes. Recognizing that the role of the AP is a contemporary role in many geographical locations, reported in the ICN Report [4], it is not surprising that countries like the USA, where AP roles are well established lead the way in the conduct of primary research. Countries faced with health disparities, due to social and economic factors, strive to develop the AP role. However, support in these countries to deliver the fundamentals of AP education is lacking [4]. Abandoned AP education initiatives and underfunding of the AP role, impact on the global reach of SBE which also impacts or hinders the conduct of SBE-related research. Where an AP role with broad AP competencies, for example advanced health history and physical assessment competencies, is established, it would facilitate the exploration of the SBE experience and thus replicability of studies outside of the USA.

Of note evidence syntheses included in the review, the yield and origin of publication are dispersed more geographically albeit in small numbers. Primary research on SBE in AP programmes with a wide geographical reach will add to a more robust perspective of the scientific discussion where consideration of the cultural nursing and midwifery nuances of AP education of nations become embedded.

In advancing the science on SBE, the publication of simulation standards provides a foundation or blueprint for conducting and reporting research in this area [170]. In Europe, the recent publication of the ASPiH standards, highlight the requirements for robust and rigour in design of SBE experiences and underscoring the need for best practice [171]. Furthermore, for readers of SBE research, the standards provide a template to benchmark the quality of the SBE experience to objectively critique emerging research. Through the coordination of SBE experiences in planning, implementation and evaluation of SBE, the INACSL and ASPiH standards provide a road map, for all nursing and midwifery educators, to provide a common understanding and language. This guidance is of particular importance for novel simulation educators seeking to initiate and integrate SBE within AP curriculum but lack the resourcing and expertise because of economic or geographical constraints. In a recent consensus publication, simulation-based practice in healthcare, the authors advocate for greater communication of the benefits of SBE with policy makers, healthcare leaders and health education institutions [174]. Understanding that SBE is delivered across the spectrum of modalities, from low cost to expensive technologies, lends itself to adopting a creative approach in the design and implementation of SBE experiences. Most importantly, the principles and adherence to the standards of best practice, when applied, may transcend the cost barriers underpinned with knowledge of simulation practices and educational theory in active teaching and learning.

In considering the design, characteristics traits and implementation of SBE, there is evidence of expansion of SBE into underexplored areas and topics that were previously associated with actual clinical practice exposure. This includes the array of communication competencies which includes difficult conversations or delivering bad news, mental health advanced communication skills, sexual health, sexual violence and conversations on sexual identity and obesity thus recognising and addressing the diversity of needs within the health population [43,60,106,157]. Study reports, on diversification of SBE AP content, described student participants’ acknowledgement of the challenges of the experience. The safe zone of practice and feedback from SP, often with personal insight, was important for the participants to directly influence practice [89,108]. Another point of note identified in this scoping review, is the acknowledgement of the need for interprofessional SBE. Quality healthcare delivery does not occur in isolation. It occurs because of diverse professional collaboration and SBE experiences should mirror the realities of working in healthcare teams. The emerging research with SBE at the interprofessional level, that includes the AP attests to the commitment of all healthcare educators in addressing the same goals of safe quality healthcare. Furthermore, interprofessional SBE recognizes the similarities and the difference perspectives of the healthcare professions in training before engaging in real clinical interactions [175]. One of the challenges in the delivery of interprofessional SBE is the logistical and coordination skills required to amalgamate SBE teaching and learning opportunities given the diversity in college or university timetables and is also reliant on the commitment of educators to support and facilitate these SBE experiences.

This scoping review found an explicit under-representation of guiding education theories as a foundation in the research process of the included studies. Less than 50% (n = 53) of included records referenced an educational theory. Fey et al. identified this important criterion in the overall quality assessment of primary SBE research and it has been raised in the nursing and midwifery education literature where educators in the professions are charged with falling short of educational scholarship when the theory or conceptual frameworks are not evidenced [176,177,178,179]. This lack of scholarships limits the impact and future direction of nurse and midwifery educational research in simulation. In contrast educational scholarship is recognized as the concentrated effort through the robust and rigorous execution of research in adding to the evidence base for the purposes of discovery and implementing change [179].

The strengths of our scoping review include the comprehensive search strategy of the current state of SBE in programmes leading to the award of AP on programme completion. In addition, the extensive search included both nursing and midwifery databases as well as general educational databases which were searched by an expert subject librarian with extensive JBI scoping and systematic review search skills. The broad aims and objectives of the scoping review identified several gaps in knowledge that justified the conduct of this scoping review. This review also identified areas in AP programmes that integrate SBE into previously underexplored health topics. Topics that involve challenging or difficult conversations, such as sexual health, mental health, women’s health, violence, abuse and end of life care are examples for further research. This is evident from the expansion of content in programmes to address population specific needs. One notable limitation of the review is the absence of literature on SBE in the context of midwifery AP with no records identified. Furthermore, it is apparent that the modalities used for SBE have evolved, however this review did not focus on these nuances, rather it examined the principal foundations of SBE methodologies. Adhering to scoping review methodology [22,23], a quality assessment of included studies, was not undertaken; this may, however, limit the interpretation of the findings as the quality on which the findings are based is unknown. Both Fey et al. [176] and Cheng et al. [178] have raised concerns about the reporting conventions of SBE research. Although the depth of the reporting was not explored in this review, for example, design and method elements beyond that of the overall study design, our reporting elucidated educational theories and reported standards of best practice which will inform future SBE development. All studies included were reported in English, with minimal to no representation from economically and budgetary constrained countries. This potentially limits the applicability of the review findings to these geographical areas. Furthermore, the role of the AP is a contemporary role in many countries further limiting the geographical representation of SBE in AP education primary research.

This scoping review examined the extent and types of available evidence on SBE for nurse and midwife AP education. SBE as an educational methodology is recognized as an educational research area that is growing. Recent global events have triggered healthcare educators to look beyond traditional education methodologies. The change and willingness to adapt in times of healthcare uncertainty demonstrates leadership is navigating healthcare education that continues to ensure that the AP is adequately prepared. However, the available evidence is limited to the USA mainly. The generalisability of the findings for other countries that are adopting the use of SBE at the AP level needs to be explored.

The adoption of SBE in advance practice programmes is growing. Further research is needed, however, for SBE as a teaching and learning methodology in other geographical locations. The publication of the Global Consensus Statement is the culmination of a substantial body of work by a community of practice. Funding research in SBE healthcare education must be prioritized by funders and other key stakeholders with responsibility for healthcare delivery oversight. Furthermore, this scoping review highlights the need for research to include speciality tracks that include mental health, intellectual disabilities and paediatrics and professions such as the midwifery to include women healthcare needs. The impact of debriefing models or frameworks, in AP education, is an area for further investigation. In addition, the methodological choice of primary studies identified in this scoping review are representative of studies adopting quantitative methods but there was a lack of consistency in reporting the required standards of best practice such as those developed by INACSL or ASPiH. Additionally, there is a need to broaden the evidence base and understanding of the concept of SBE through different methodological paradigms including qualitative and mixed methods enquiry.

Supplementary data are available at Journal of Healthcare Simulation online.

None declared.

The authors collectively contributed to the conceptions, planning, reviewing and reporting of the review. Drafts of the manuscript were written by KMcT. All authors (PM, CMcC, VS and MT) commented on iterations of the manuscript. CMcC, VS and MT contributed to the final production of this document. All authors read and approved the final manuscript (KMcT, PM, CMcC, VS, MT and JEC).

No funding received.

None declared.

None declared.

None declared.

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

30.

31.

32.

33.

34.

35.

36.

37.

38.

39.

40.

41.

42.

43.

44.

45.

46.

47.

48.

49.

50.

51.

52.

53.

54.

55.

56.

57.

58.

59.

60.

61.

62.

63.

64.

65.

66.

67.

68.

69.

70.

71.

72.

73.

74.

75.

76.

77.

78.

79.

80.

81.

82.

83.

84.

85.

86.

87.

88.

89.

90.

91.

92.

93.

94.

95.

96.

97.

98.

99.

100.

101.

102.

103.

104.

105.

106.

107.

108.

109.

110.

111.

112.

113.

114.

115.

116.

117.

118.

119.

120.

121.

122.

123.

124.

125.

126.

127.

128.

129.

130.

131.

132.

133.

134.

135.

136.

137.

138.

139.

140.

141.

142.

143.

144.

145.

146.

147.

148.

149.

150.

151.

152.

153.

154.

155.

156.

157.

158.

159.

160.

161.

162.

163.

164.

165.

166.

167.

168.

169.

170.

171.

172.

173.

174.

175.

176.

177.

178.

179.