Whilst virtual reality simulation (VRS) has been established in the teaching of anatomy and technical procedures, its use within acute medicine remains relatively unexplored. Furthermore, whilst VRS has been shown to have a role in improving assessment outcomes, its impact on real-life clinical practice is unknown. This pilot study investigated VRS in the teaching of acute medical topics and explored the transferability of learning from the VRS sphere into real-world clinical practice.

Learners partook in a series of small-group, VRS teaching sessions on acute medical scenarios, using Oxford Medical Simulation software on Oculus Quest headsets. We conducted semi-structured interviews with the learners at baseline (week 0) and at follow-up (week 12) to explore a range of issues relating to transferability and quality of learning, the debrief and barriers to engagement. The interviews were recorded, transcribed and analysed to highlight common themes and concepts.

Participants transferred multiple facets of learning from the VRS sphere in to real-life clinical practice. Additionally, VRS was considered psychologically safe and encouraged independent practice, whilst the debrief was universally held as invaluable in facilitating reflective learning. There were negligible troubleshooting issues with the VRS system and barriers to attendance were secondary to pressures common to all modalities.

Our study is the first to show a clear role for VRS in the teaching of acute medicine and, more broadly, demonstrates how learning is potentially transferable to real-life clinical practice. Furthermore, we explore the relationships between VRS and high-fidelity simulation and propose ways in which VRS might be best employed as part of postgraduate medical training.

The way postgraduate education is being delivered is rapidly changing, with the rate of this change having been accelerated by a variety of pressures. From the patient’s perspective, there are changing societal expectations relating to patient safety, with reservations about being ‘practiced on’ by medical students and training doctors [1]. From a learner’s perspective, there is an ever-present desire for more clinically relevant learning opportunities, made more acute by the coronovirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic’s limitation of direct clinical encounters with patients [2–5]. Conversely, this must be balanced against the criticism that purely hospital-based learning has become a too expensive and resource-intense approach [6].

These drivers, amongst others, have contributed to the growing prominence of simulation-based education (SBE) within postgraduate medical education in the United Kingdom. SBE is now included as a core learning modality within several UK postgraduate training programmes, with a minimum number of hours often mandated. These include curriculums for foundation doctors (FDs, encompassing pre-registration (F1) and first-year post-registration (F2) doctors in the United Kingdom), specialty medicine, surgery and anaesthetics [7–10]. As part of the evolution of SBE, virtual reality simulation (VRS) has emerged as an increasingly prevalent and accessible modality. Whilst VRS can have a diverse application within medical education, current literature demonstrates that its use has largely been restricted to the teaching of anatomy and surgical procedures, with a relative dearth of experience of its use in the teaching of medical topics [11–14]. Even when used for the training of cognitive medical skills, VRS has been used in the context of relatively simple clinical algorithms, such as basic life support, with its potential use around more complex and nuanced medical presentations remaining largely untapped [15,16]. Furthermore, whilst learning in the VRS sphere has been demonstrated to improve performance in examination and assessment settings, its transferability to learners’ real-world clinical practice has yet to be demonstrated [17–19].

To help address these gaps, the aim of this study was to understand learner attitudes and beliefs pertaining to existing teaching methodology and then to assess the value of VRS and its transferability into real-world clinical practice. To achieve this, we conducted semi-structured interviews with FDs who had participated in a medical VRS teaching programme at our centre. This qualitative study allowed us to explore a variety of themes that centred around transferability of learning, as well as the quality and accessibility of learning, with a firm focus on the learners’ perspective.

Following a successful pilot of large-group teaching sessions (10–30 learners per session) introducing VRS to the FDs at our centre, we aimed to recruit a focus group of FD learners who would participate in a series of further, small-group (1–5 learners per session) VRS teaching sessions and conducted semi-structured interviews 12 weeks apart. We extended an email invitation to all of the FDs (86 F1s and 126 F2s) across the four sites at our hospital trust.

Our VRS teaching programmes use a library of standardized medical scenarios developed by Oxford Medical Simulation, which we ran on Oculus Quest head-mounted displays [20]. For each scenario, learners are required to provide medical assessments and initiate treatment in virtual clinical environments that aim to recreate pressured, real-life clinical experiences where the patients’ physiology responds dynamically to the user’s actions. After the scenario, FDs were offered an in-person debrief facilitated by a senior clinician. Teaching session topics related to the management of acute medical emergencies; upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB), exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) and sepsis-related delirium. Each teaching session involved one facilitator and 1–2 learners and lasted approximately 30 minutes.

In parallel with these sessions, we aimed to conduct 15- to 20-minute semi-structured interviews with the learners at baseline (week 0) and at follow-up (week 12). At the week-0 baseline interview, we aimed to explore the learners’ views on postgraduate medical education, barriers to engagement with educational opportunities, and their views on simulation and VRS more broadly. At the week-12 follow-up interview, we aimed to explore the transferability of any learning achieved within the VRS sphere into learners’ real-life clinical practice as well as exploring other aspects including their reception of VR as a modality, the value of the teaching session debriefs, accessibility and troubleshooting with the VRS system, and opinions on the content of the scenarios.

We aimed to approach the interview from the learner’s perspective and to adopt a semi-structured format to help capture complex and subtle themes, whilst allowing for a flexible and participant-orientated approach. Our intended audience for our findings would be the medical educational community that uses, or is looking to use, VRS and the information gained from this evaluation would aim to guide educators in the use of VRS in clinical training. Interview guide questions were designed by the two lead authors, with a consensus on the inclusion and wording of the final question list being met after a group discussion amongst our centre’s VRS faculty (Supplementary Material S1).

The interviews were conducted and recorded either in person or over telephone, before being digitally transcribed using Microsoft Word Online. The transcripts were then screened and corrected manually by the authors.

Thematic analysis followed the structure advocated by Braun and Clarke and expanded on by Kiger and Varpio [21,22]. The transcripts were analysed using NVivo software, by the two authors who conducted the interviews, to highlight common themes and concepts. We worked within a post-positivist epistemology when conducting our thematic analysis and used a mix of inductive and deductive approaches in deriving codes and themes that were relevant and provided insight into our research goals [23]. Codes and themes were developed and applied individually before being compared. Commonalities and discrepancies were discussed between the authors until a consensus was reached, enhancing reliability (Supplementary Material S2).

We referred to the COREQ criteria when designing and implementing this study[24]. This project was reviewed by the University of Oxford’s Research Governance, Ethics and Assurance Team, who determined that the activity is best understood as an evaluation of educational provision, and thus did not require ethics review. This work was also registered with the Oxford University Hospital Quality Improvement Board (audit number 8202).

A total of 212 FDs were contacted to participate in this education evaluation study, with 10 respondents. Of the 10 FDs who replied to the study invitation, 5 FDs subsequently engaged with at least one teaching session or interview and were therefore included in the study analysis (Table 1). The remaining five FDs were contacted by email to explore why their interest did not translate to engagement with the programme but none replied. A total of 12 teaching sessions were delivered over the study period. All five learners who completed at least one VRS session completed both the baseline interview at week 0 and the follow-up interview (range week 11 to week 16 from baseline). All themes derived from the baseline and follow-up interviews are collated in Table 2.

| Learner | Gender | Stage of postgraduate training | Previous VRS exposure | Previous hi-fi sim exposure | Baseline interview | Follow-up interview | Teaching topics attended | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UGIB | COPD | DKA | Delirium | |||||||

| 1 | M | F1 | Yes | Yes | 20/03/2023 | 13/06/2023 | X | X | X | |

| 2 | F | F1 | Nil | Yes | 28/03/2023 | 05/07/2023 | X | X | ||

| 3 | F | F1 | Nil | Yes | 28/03/2023 | 20/07/2023 | X | |||

| 4 | M | F1 | Nil | Yes | 25/04/2023 | 22/06/2023 | X | X | ||

| 5 | M | F2 | Yes | Yes | 04/05/2023 | 21/06/2023 | X | X | X | X |

M, male; F, female: F1, foundation doctor year 1; F2, foundation doctor year 2; VRS, virtual reality simulation; hi-fi, high fidelity; UGIB, upper gastrointestinal bleeding; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DKA, diabetic ketoacidosis.

| Themes derived from baseline interviews |

| 1. Learners value learning that is transferable to their real-world practice |

| 2. Learners value teaching that centres on common patient presentations and practical aspects of their jobs, and that is delivered by a clinical expert |

| 3. Learners value formats that are face-to-face and/or involve simulation |

| 4. Learners’ exposure to simulation-based education is limited, despite its value to learners |

| 5. Limited learner engagement with learning opportunities was largely secondary to barriers that are global to all modalities of learning |

| Themes derived from follow-up interviews |

| 6. Learners can transfer multiple facets from the VRS sphere to their real-life clinical practice including clinical knowledge, communication skills and task prioritization |

| 7. VRS is a modality that is valued by learners in the teaching of the management of acute medical scenarios |

| 8. The VR environment affects independent practice by influencing how learners behave and what they can learn |

| 9. VR simulation is useful for lower-level cognitive learning, allowing the development of higher-level learning and higher-order non-technical skills during hi-fi simulation |

| 10. The post-scenario debrief facilitates learner reflection and advances learning |

| 11. Attempting a scenario in VR makes the subsequent debrief more engaging |

| 12. Limited learner engagement with VRS learning opportunities was largely secondary to barriers that are global to all modalities of learning, with VRS-specific barriers being a minor contributor. |

| 13. Learners found the VR system both usable and reliable, though rare troubleshooting issues can affect the quality of learning |

| 14. Postgraduate learners would value VR simulation being incorporated within their structured training curriculum |

VR, virtual reality; VRS, virtual reality simulation.

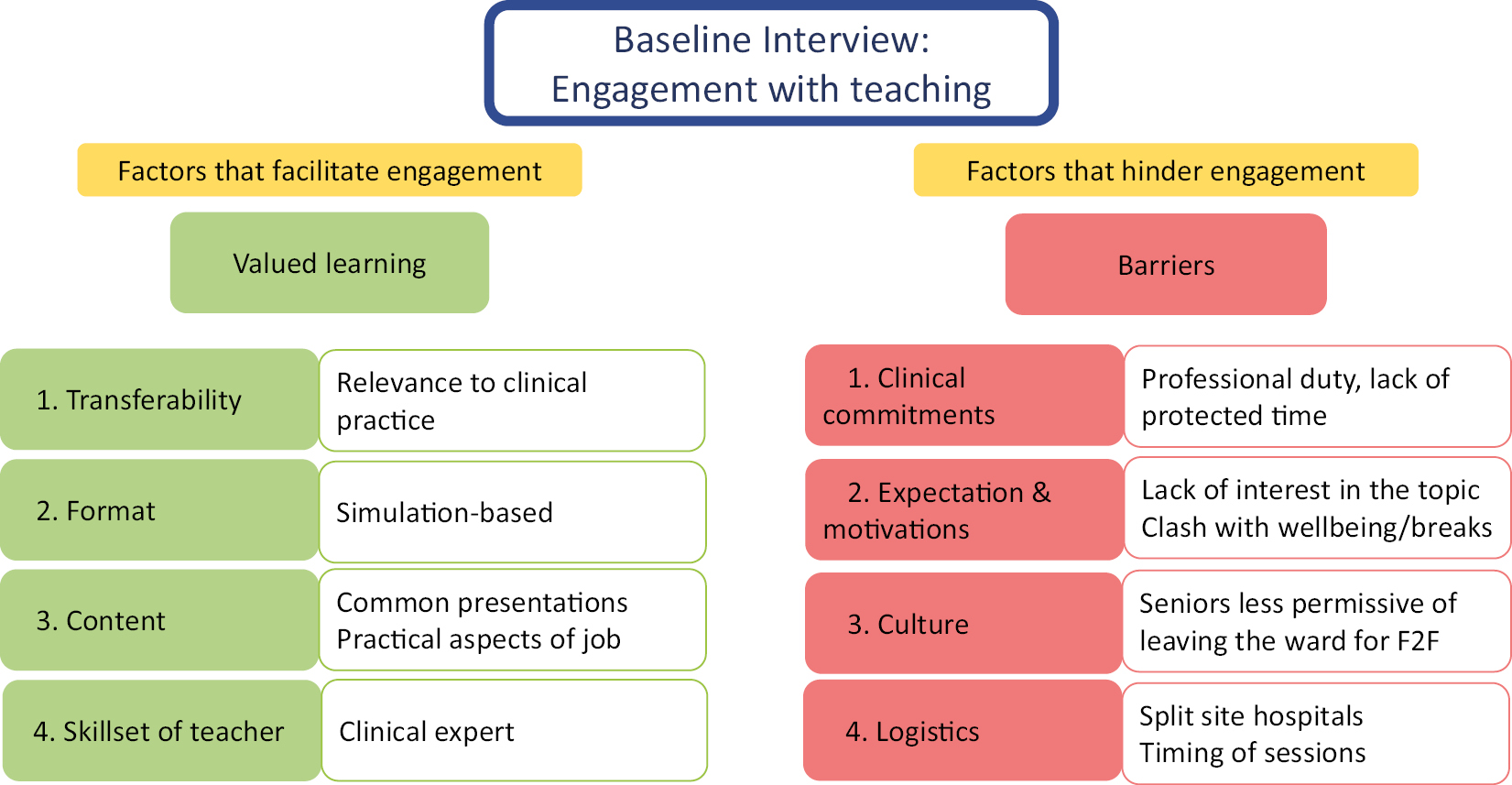

The two key themes derived from the baseline interview were valued learning within the teaching sessions and engagement with teaching. With respect to engagement, the doctors spoke about factors that facilitated or created barriers to their participation in education during their foundation years. The factors that facilitated their learning related to the features of teaching that they most valued. This is represented in the diagram below (Figure 1):

Factors that facilitate and hinder learner engagement with teaching.

When exploring teaching that was valued by the learners, the foremost and universally expressed desire was for teaching that was immediately transferable to their clinical practice. When exploring the drivers behind this transferability, these related to the format of delivery, the topic content and the skillset of the deliverer.

The participants broadly expressed a preference for formats that were face-to-face and mimicked their real-life working environment and this was most frequently quoted as being simulation training, though ward-based teaching sessions were also valued. However, learners’ exposure to SBE is limited, despite its value to learners. Whilst learners described SBE learning experiences as being particularly fruitful, with its realism and feedback formats being frequently praised, most learners described having had sparse exposure in medical school and up to a single session in their F1 year. Demand for more simulation was a common sentiment, due to the powerful learning it was perceived to elicit and the transferability of that learning.

At med school, we just had a couple of days of simulation with the model … it was really well run – the tasks were really realistic and the feedback was really good.

I would actually even go as far as to say you can’t get enough exposure to [simulation] … it’s what you would do in a time-pressured and difficult situation (on the job).

With regards to VRS in particular, two of the learners had had one previous exposure in medical school. This was in a similar format to the sessions run as part of this study and both deemed it to be a positive experience, with its realism, flexibility, level of immersion and elements of gamification all praised. However, the content was described as basic and not fully interactive and there were minor issues related to troubleshooting and limited headset availability.

Though learners expressed a preference for clinically applicable topics, they described their exposure to such sessions as being infrequent and ad-hoc. Learners felt that valuable protected-teaching time (whereby learners are excused from their clinical commitments for the duration of the educational session) was instead consumed by curriculum-mandated topics that the learners did not see the value in, and that were delivered in an apparently random order. The desire for relevant topics was not limited to their clinical responsibilities but also applied to the common administrative aspects of their duties such as death certification and cognitive screening. Importantly, however, non-clinical topics that cannot be distinctly and discretely applied to clinical practice, such as professionalism and well-being, were largely deemed to be patronizing or an ineffective use of protected teaching time.

The best thing you can do to learn how to manage an acutely unwell patient is by managing an acutely unwell patient but you can’t do that every day.

I think any of the teaching that’s on, like, common presentations that we come across a lot – with key management, investigations and, yes, and things to know – yeah, are the best sessions to have because they’re the ones we need. We need extra help with actually being juniors on the job – so, clinical things that you’re going to apply back on the wards [are valuable].

Learners valued sessions delivered by clinicians with a relative expertise in the field – including doctors, nurses and allied health professionals – as they could facilitate complex discussion points that would otherwise be challenging for the learner to address independently. Furthermore, teaching delivered by senior doctors, in particular, was highly regarded as having previously been in the learners’ shoes, it was felt they could more closely relate, understand the challenges of a given topic and pitch the teaching accordingly. Non-clinician facilitators could be seen as patronizing if they were not sympathetic to the challenges that doctors face as part of their job.

[Regarding teaching delivered by a non-clinician] It was just quite strict on what we should be doing and what we shouldn’t be doing without really putting it in the context of how busy it is sometimes, and how difficult it is. When you’ve got multiple jobs to do, it’s not always possible to do everything.

Clinical commitments and busyness in the hospital wards were a universally quoted reason as to why teaching was difficult to attend and the concept of protected teaching time was mentioned as a welcome facilitator of attendance.

I would say that the biggest barrier is probably, ‘what is the demand on the ward jobs?’. Whichever department you’re in; the jobs for the day and how supportive are [seniors] in terms of you leaving, and not having to catch up at the end of the day, outside of hours.

Even if protected, learners would opt against attending a teaching session if the topic ‘is not personally interesting to me’ or is ‘going over old ground’ and there were references to a feeling that teaching was targeted towards fulfilling a unilaterally agreed curriculum, rather than a trainee-led one. Similarly, internal motivation and concerns about clashes with personal well-being compromised learner attendance, with immediate well-being given a priority over learning.

Having enough time to both go to teaching and eat lunch is sometimes an issue. So lunch and teaching will be at the same time … I would have thought, once a week for an hour, we could have teaching and have lunch (at separate times). I don’t see why that should be a problem.

The concept of a changing culture around trainee education was also highlighted, in that some clinical seniors were described as being less permissive of juniors physically leaving the ward for teaching. This shift was attributed to the pandemic having changed optics around teaching, whereby there was an expectation from seniors that teaching would be virtual, on-demand or both.

I think that probably changed during COVID when everything went virtual, because then people could do the virtual teaching alongside their jobs or discharge summaries or something like that. And so I think it became less ingrained in the sort of culture of the ward that [trainees] would be leaving for a short amount of time.

Cross-site access to teaching within a split-site hospital trust was also described as a hinderance, whereby learners were more unlikely to be able to physically attend face-to-face sessions on separate sites either due to transport issues or due to the added time needed to attend a session that is further away. Similarly, the timing of teaching sessions influenced their ability to attend, with morning sessions tending to clash with ward rounds.

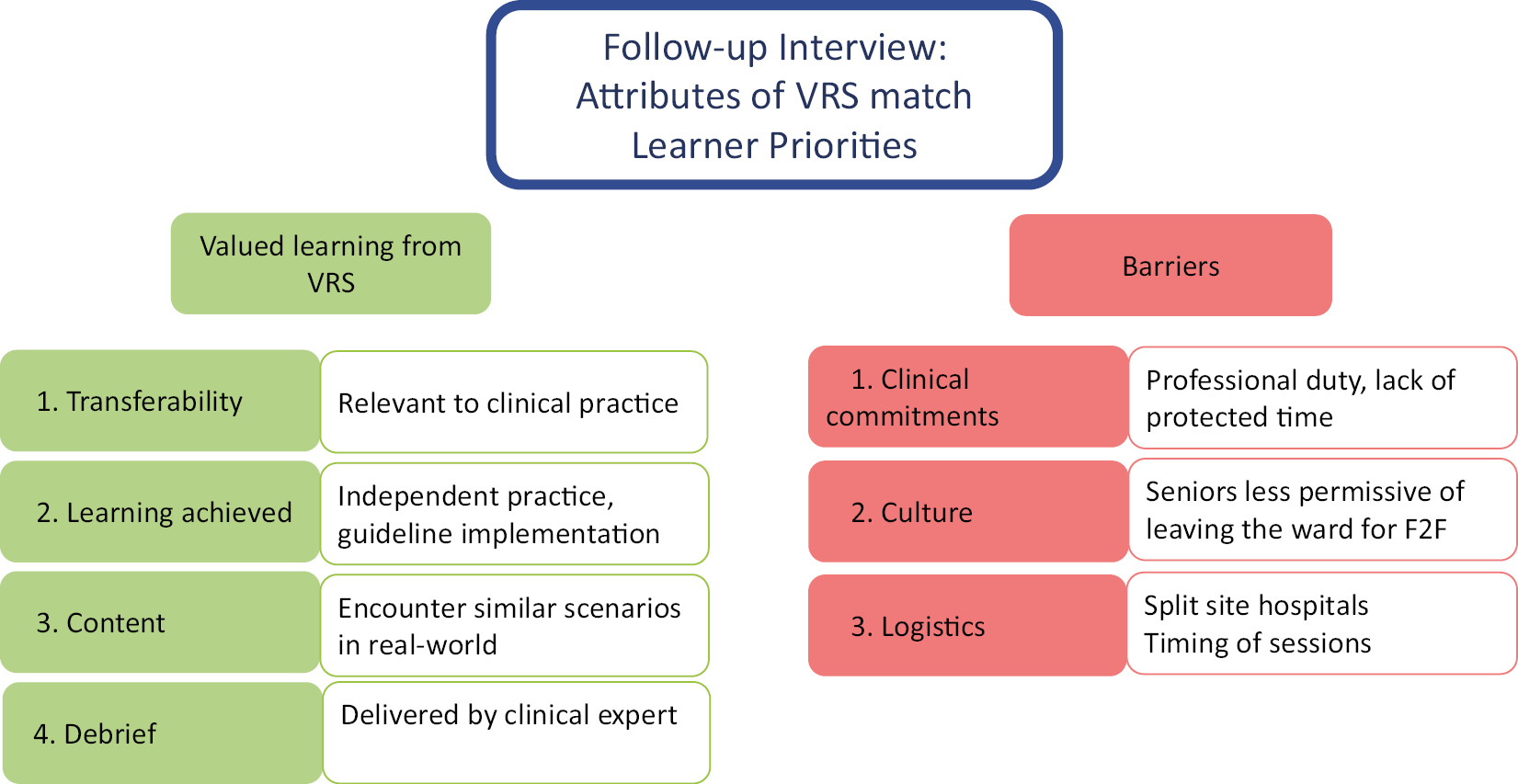

At the follow-up interview, we explored the learners’ experience with VRS and thoughts around implementing VRS more formally within a postgraduate medical curriculum. Engagement with learning was again discussed. The main themes elicited at the follow-up interview related to the impact of VRS education on clinical practice and the attributes of VRS that affected this and it was clear that many of the virtues of VRS mirrored the learner priorities outlined in the baseline interview (Figure 2).

Attributes and impact of VRS.

Learners described that they were able to transfer multiple aspects of the learning they achieved in the VRS sphere into their real-world clinical practice. Learners quoted that they applied clinical knowledge that was gained through completing a VRS scenario and that the VRS experience improved their ability to make decisions, prioritize their actions, communicate with colleagues, and follow and apply guidelines when they encountered similar scenarios in the real world. Additionally, two of the learners commented on how the VRS scenario also forced them to consider real-world ergonomics that affect accessibility of resources and colleagues. The nature of the cohort’s job rotations also demonstrated that transferable skills, such as communication with seniors and guideline application, could be honed in acute medical VRS scenarios and then applied even in non-acute clinical settings (e.g. primary care or psychiatry).

For COPD it has been quite useful, I would say. It’s been quite useful just knowing, just increasing confidence in what order in which you would do things, and things to kind of look out for to be concerned about, and when you would want to escalate to your senior more urgently than maybe at other points? And also the order in which you would go about doing the investigations, and then which medications you would maybe start with, and then which ones you can then look into later on.

I’ve had one situation where I did deal with an acute scenario in GP. I think that management was very, very different because we did not have access to the things that you would usually have access to in a hospital setting. I think the key thing that probably was helpful was actually dealing with the medical registrar over the phone – you do get some kind of sample ideas of what they would come back with, the sorts of things that they ask.

However, one learner commented on how the textbook patient presentations within the VRS scenarios made the diagnosis quite apparent, which is not necessarily transferable to the real world. This limited their ability to access and re-surface prior learning as the connection between the VRS and real-world cases was harder to identify.

Actually, I’ve seen a GI bleed, but I think it presented differently to how it did in the simulated session and it was slightly more vague I think. And so I think that one was maybe, I’ve not put into practise as quickly … I’ve not seen an upper GI bleed where I’ve immediately thought ‘that’s a GI bleed’ and then gone through it.

The learners’ perception of the VRS environment and scenario content impacted their behaviours within the scenario, and therefore on what they learned. Three of the learners described how attempting a VRS scenario through a closed-system headset increased their sense of psychological safety, due to a lack of direct observation from faculty and because the patient was virtual. This helped to ‘eliminate distraction and help focus for the duration of the scenario’ whilst also allowing them to be ‘more experimental’ as ‘no one is going to get hurt’. The independence offered by an unprompted scenario within a closed system also meant that learners felt encouraged to make independent decisions on a ‘blank canvas’ where they were obliged to ‘put everything together yourself’. However, learners described how this benefit was offset by the inability for direct feedback from faculty on their in-scenario actions, as these were unobserved in real time. To steer their practice, the learners instead used the intra-scenario guidance and referenced the gamified nature of the scenarios as providing motivation and structure to their approach.

You have more room for experimenting with different investigations, and then different treatment options and seeing what the treatment does to the vitals or the investigations like [arterial blood] gases or, yes, and perhaps it feels less like Big Brother is watching you sort of thing.

The perceived realism of the scenarios and their interactivity also influenced learner behaviour. All the learners commented on their enjoyment of the immersive learning experience, though there were multiple comments that the accelerated representation of time, the use of drop-down menus to interact with patients and the inability to physically perform practical procedures all limited the scenarios’ realism and their ability to suspend disbelief. Conversely, one learner who had previously experienced VRS as a medical student found it easier to suspend disbelief as an FD, as their real-life professional experiences as a doctor provided a substrate for immersion.

I think things happen, obviously, a lot faster than in real life. And that obviously completely changes the dynamic. You can chain a bunch of actions at once, which is not like real life … and then you can be doing something else while something else is going on in the background. And, in that sense, it’s very unreal.

Multiple learners expressed a view that the debrief was instrumental in advancing learning. The dominant theme related to the debrief facilitating reflective learning and consolidation of the thought processes that occurred during the scenario itself. The learners valued the debrief as a period where decision-making could be ‘dissected’ with a senior in real-time, something that is often unachievable in their clinical practice, in order to effect more powerful learning.

Furthermore, learners gave examples of how the debrief allowed them to cover more complex themes, by exploring how the scenario may have hypothetically progressed, which they subsequently directly applied in their real-life practice. One example related to a debrief discussion around non-invasive ventilation (NIV) following a COPD scenario, which allowed one learner to better understand instructions from seniors as well as the contribution to management decisions when treating a critically unwell patient with COPD in real life.

I think while you’re in the middle of a scenario, you’re thinking very much about what’s the next thing to do. And you’re not necessarily thinking about what’s just happened and what can be improved. And so you need that time afterwards, where you’re just a little bit separated from what just happened, to get learning points for next time.

We talked about NIV after the COPD station, which has come in useful. So I had a patient and he was quite unwell, and he was on NIV. And when sorting him out we were talking about the settings for the NIV, and I was just able to understand that – and that was only after the session that we had.

Relating to the VRS modality’s impact on the subsequent debrief, attempting a clinical scenario in virtual reality seemed to individually engage each learner in a way that traditional, classroom-based, small-group case-based discussion teaching may not. Learners point to the idea that the debrief seems more relevant and is more engaging, as the scenario has been completed independently by each learner. Multiple learners expressed similar views along this line:

[Regarding VRS] In a sense, if you’ve done it, it’s kind of more personalised actions you’ve taken? If it’s a [traditional classroom] case based, you might not be going through exactly what you would have done in that moment. It’s more, general, I suppose.

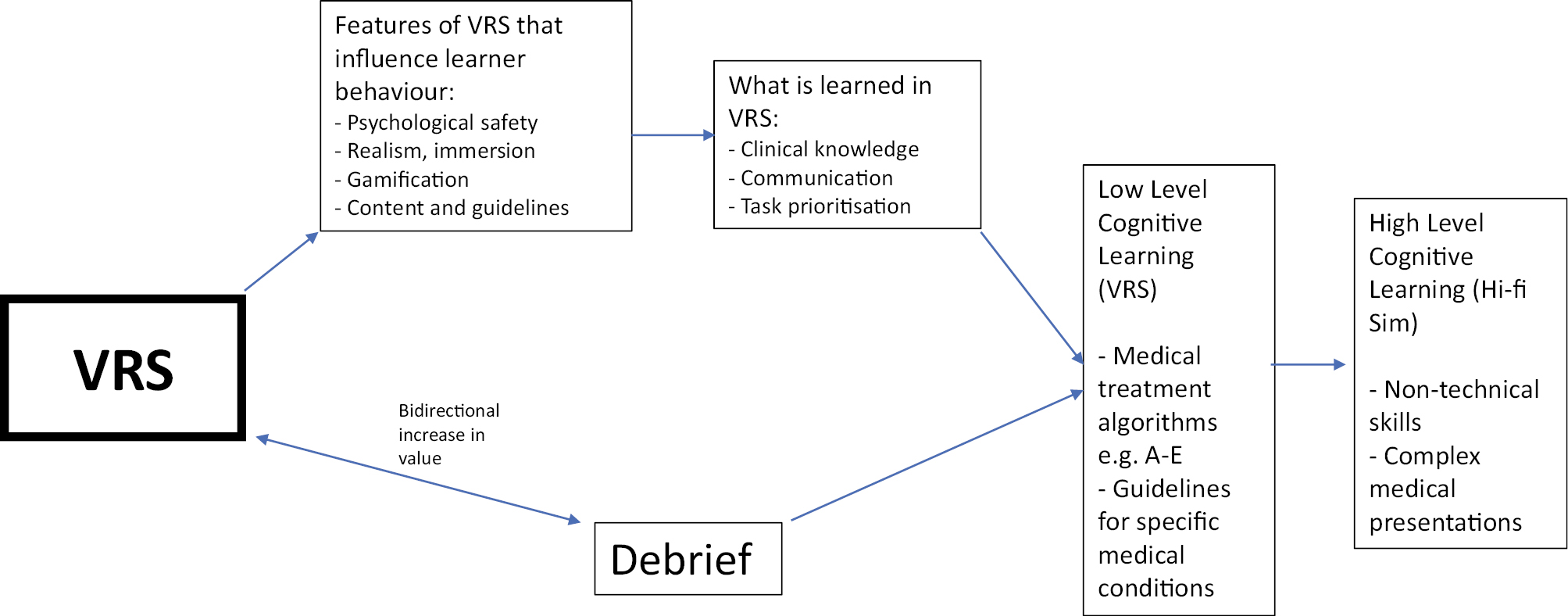

The learners were encouraged to reflect on the relative merits of both VRS and hi-fi simulation and how they might influence how each modality is best employed. Multiple learners described that the VRS sessions felt more psychologically safe, allowing progression through a scenario using guideline-assisted decision-making, but that the limited realism affected what they learned. It was a commonly held viewpoint that the VRS sphere consolidated the learning of medical algorithms and guidelines, whereas the additional realism offered by high-fidelity simulation allowed for more of a focus on the human factors within a stressful scenario.

In the actual [hi-fi simulation] suite, I prefer it because I think you feel a bit more stressed, maybe, than in a VR scenario and so you have that, not as stressed, but I suppose it’s a bit more realistic in that sense. That you’re actually doing stuff with your hands, which can also be quite useful, and involves communicating with other members of the team. Whereas the VR sessions I did were kind of a bit automated in terms of asking the patient questions. I suppose it’s good to go over different emergency presentations and then you can maybe practise it further in a [hi-fi] simulation session – so on that front [VRS] could be a useful tool.

[VRS] could also be helpful before a high-fidelity sim session so that, when you’re going in [to a hi-fi simulation session], it’s actually trying to directly apply it in a real life thing … rather than having to learn it for the first time while you’re in the middle of the session.

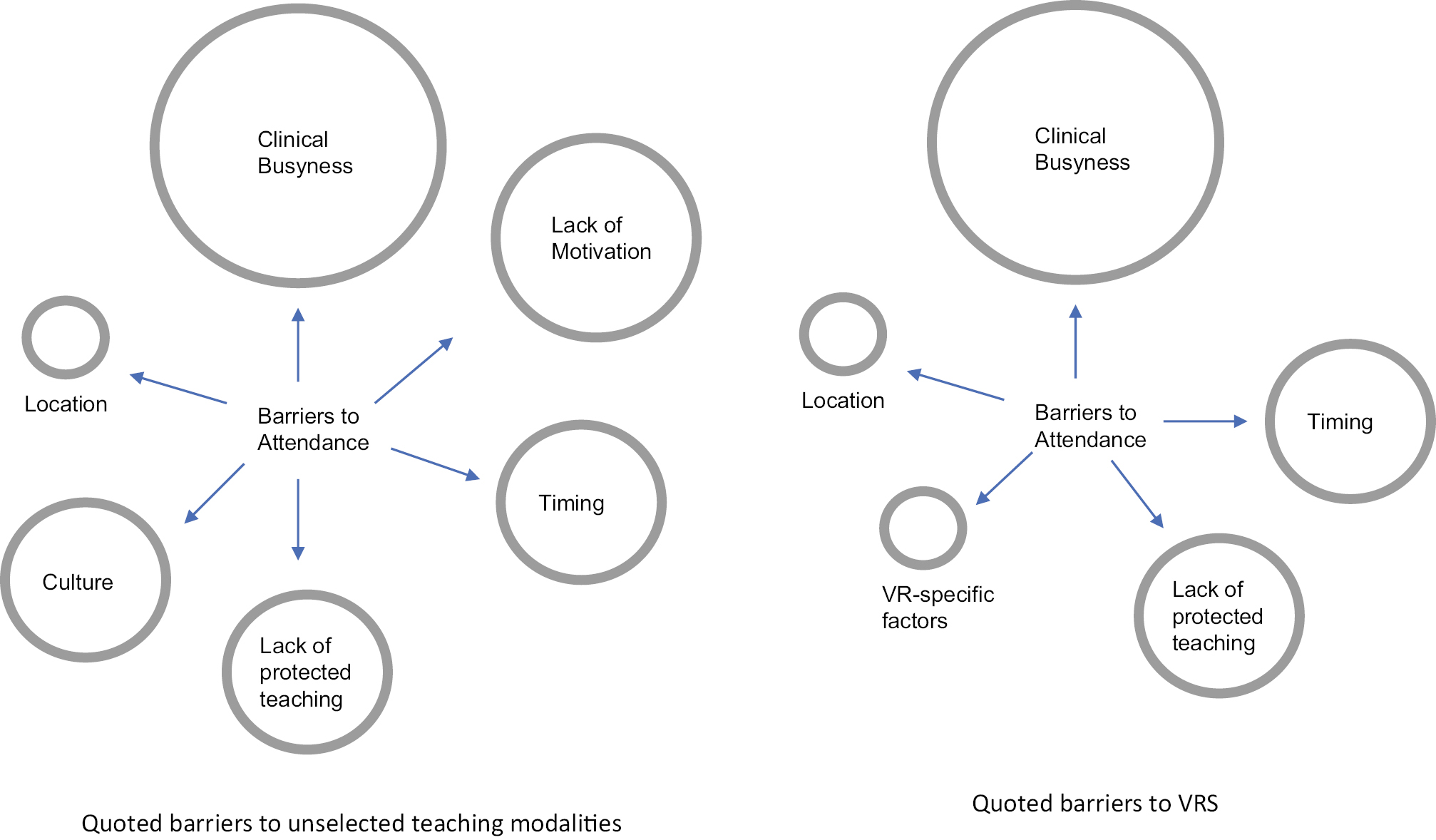

Throughout the study, the learners clearly had difficulties engaging with the VRS learning opportunities. Learners would go long periods in between sessions and numerous planned sessions had no attendees signed up. In keeping with data from the baseline interviews, job busyness and prioritization of clinical commitments were the foremost factors quoted by all the learners. Even if the learning opportunity was a valued one, learners prioritized clinical work, in order to finish their working day on time, over non-mandatory teaching opportunities. And whilst protected teaching time for mandatory teaching was championed by the learners, it was a commonly held view that even this was subject to clinical pressure.

We’re meant to have Tuesday lunchtime teaching. It’s very, very difficult to attend it … ward round would go on until 12:30 at least, so I would barely ever get to the teaching…..It would be great to have protected teaching that is planned … but [their clinical seniors] are often like ‘it’s too busy’….

Timings of teaching sessions were frequently quoted as a barrier to engagement, though there was a clear lack of consensus within the learner group, and inconsistencies even within individual learners, about whether fixed session times versus a more fluid, ad-hoc approach would best facilitate attendance. Employing both approaches in turn yielded similar attendance figures and despite focus group consensus for ad-hoc sessions following poor initial attendance, all learners bar one paradoxically subsequently cited the absence of a regular time slot as a barrier to their attendance, at follow-up.

The location of the teaching sessions was also cited as an obstacle. The majority of FD teaching opportunities are held on the main hospital site but the hospital trust’s split-site, coupled with the rotational and shift-based nature of the learners’ jobs, meant the learners were often not able to physically attend.

Different sites sometimes have teaching as well. And so [being able to] leave the ward and go for more teaching has been a bit tricky I think … It’s sometimes difficult to, to leave unless you know it’s every week, this time to this time, and the rest of the team is aware that you have that, otherwise, sometimes you feel a bit bad leaving.

There were no VRS-specific barriers that limited learner attendance at our study’s sessions. Four out of the five learners experienced no troubleshooting issues when using the VRS system and completing scenarios. 1 learner experienced difficulties in earlier sessions, relating to both fitting the headset and to orientating themselves within the VRS domain, though these problems did not recur as they became more familiar with the system. This learner had attended both large-group and small-group VRS sessions and cited a lower faculty-to-learner ratio in the large-group sessions as a driver behind their experience of troubleshooting issues.

There was an appetite for VRS to be incorporated into the learners’ postgraduate medical teaching more formally and regularly. It was described as an accessible modality that provided a welcome adjunct to other teaching as well as to their real-life practice. In keeping with the data from our baseline interviews, learners valued the topic content, especially given that their exposure to medical emergencies was splintered by job rotations, and favoured the mode of delivery, given its level of immersion and transferability. When prompted to expand on how they might incorporate VRS in their teaching programme, the learners were keen to have ring-fenced time and envisaged it being used to complete a scenario in virtual reality, prior to a small-group debrief or large-group lecture on the topic, from a clinical expert.

I think it’s a good adjunct to other modalities of teaching that we have at the moment … I don’t think it could replace a consultant-led lecture if that’s the modality [education organisers] want to use, but it’s a good starting point and puts everyone in, like, a good case that they can apply it to …. I think the key point is protected time, yeah.

This evaluation was conducted, with a focus on the learners’ perspective, to explore learner attitudes towards current postgraduate teaching and the merits of employing VRS in the teaching of the management of acute medical scenarios. More specifically, we have drawn out themes relating to; the facilitators and hinderances of engagement with learning, the attributes and impact of VRS learning,, the relationship between VRS and hi-fi simulation, and the integration of VRS within a postgraduate medical education curriculum. Furthermore, whilst the benefits of VRS have previously been demonstrated within the fields of surgery and anatomy, this is the first paper to our knowledge that demonstrates a place for VRS specifically in the teaching of acute medical scenarios. Compared with existing literature that demonstrates a potential for VRS in improving learner assessment outcomes in an examination setting, we also provide concrete examples of doctors transferring their learning directly from the VRS sphere into their real-life clinical practice in both acute and non-acute settings.

VRS lends itself well to many of the wants that our cohort of doctors held about their postgraduate education at the time of their baseline interview (Figures 1 and 2); it is a simulation modality that is eminently transferable to their everyday clinical practice, can centre on the acute and common patient presentations that they are most eager to learn about, and can be facilitated by expert clinicians. Furthermore, whilst there is no overarching dogma on how medicine should be taught, the immersive nature of VRS provides a uniquely accessible constructivist model that does not rely on access to an acute hospital setting. This format is learner-centred, experiential, builds on existing knowledge and allows social interaction both within the VRS scenario (with VR avatars), and during the debrief. This virtual mimic helps learners explore the ‘rules of the game’ and encourages exploration, experience and experimentation by cultivating a sense of psychological safety which, in turn, promotes independent practice [25].

To achieve this, other immersive modalities would ordinarily require significant person resource and, whilst there are well-documented challenges relating to infrastructure and availability of trained faculty in running VRS, there is a unique potential for VRS to make simulation training more accessible to learners [26]. Indeed, there was a clear desire within our cohort to incorporate this modality more widely within their postgraduate curriculum, even if it were to be at the expense of more traditional modalities. One approach to optimizing the utility of VRS, that was championed by the learners, was as a substrate for case-based discussions – the VRS scenario adding relevance by allowing each learner to have individually approached the case themselves, promoting critical thinking and facilitating the subsequent application of learning in real life [27].

The learners also highlighted the symbiotic relationship between VRS and the post-scenario debrief in building on this learning. The importance of the debrief in SBE is not disputed and, whilst the value of the debrief in VRS has previously been shown to improve knowledge acquisition and behavioural performance, our learners additionally highlighted the importance of this period for reflective learning, allowing a deeper consolidation of learning to take back to their clinical practice [28,29]. This is especially important as, though medical VRS software often feature-guided, post-scenario reflective questions, these are not specific to the preceding scenario nor tailored to the learners’ behaviour in-scenario.

On exploring VRS’ relationship with high-fidelity mannequin simulation, we found the value of VRS to be in lower-level algorithmic learning, potentially liberating time in the high-fidelity suite to focus on complex presentations or on the human-factors elements of medical management. This was underpinned by perceived limitations of VRS whereby, whilst the environment was conducive to independent practice and guideline application, its realism was hampered by rudimentary person-interactions and the accelerated flow of time. This proposed relationship builds upon current literature that either pits one modality against the other or simply stratifies them hierarchically and highlights the need to tailor learning objectives to the modality being used [16,30]. Though VRS will continue to evolve, including through the emergence of voice recognition and bespoke scenario creation, the relative merits of both VRS and high-fidelity simulation means that it is unlikely one will simply supersede the other [31,32].

Our interpretation of VRS’ influence on learning is outlined in Figure 3. We propose that the behaviours that are facilitated and encouraged within the VRS sphere influence what knowledge and skills are acquired by the learner, with these learning outcomes tending to relate to lower-level cognitive learning such as the application of algorithms (e.g. A-E assessments) and treatment guidelines [33]. The beneficial effects of VRS and the debrief work reciprocally and synergistically, in that the VRS gives more relevance to the debrief by allowing each learner to attempt the scenario individually, whilst the debrief increases the value of completing the scenario by facilitating deeper reflection. The learning that is achieved in the VRS sphere provides a platform to practice higher-cognitive skills, including non-technical skills, as part of hi-fi simulation. Thus, VRS can liberate hi-fi simulation capacity for this purpose.

VRS influence on learning

Whilst learner engagement with the VRS teaching opportunities proved a challenge in our study, exploring the issues around this highlighted that the learners were constrained by the same ever-present stressors and obstacles that limit their ability to engage with any teaching programme [34,35]. Clinical commitments provided a pervasive hurdle, with protected teaching time only partially mitigating against this. Furthermore, a shift in the culture surrounding teaching was repeatedly referenced with concerns raised that the COVID-19 pandemic has fostered a default expectation from senior clinical team members that teaching will be virtual or on-demand, raising their threshold to allow juniors to leave their clinical posts to attend [36,37]. Similarly, the emerging spotlight on learner wellbeing, again amplified by the recent pandemic, and an increasing priority to finish work on time also raises the threshold at which a teaching opportunity is deemed ‘worth it’ by the learner [37,38]. Furthermore, learners wanting to have agency over what they learned, and not being subject to a paternalistically derived curriculum was also a recurrent point. There was an impression from some of the learners that they should be the main arbitrator over what they learn, and whom they should learn from, and if a particular teaching session did not fit their criteria, they would feel empowered to not attend, even it was designated ‘mandatory’ on their curriculum. This is related to teaching on discrete medical topics but also to more nebulous concepts such as professionalism. This points towards the need for co-creation of teaching programmes, to maximize learner motivation to attend. Interestingly, unlike non-VRS modalities that were explored during the baseline interviews, learners did not express a lack of motivation as being a barrier to attending VRS teaching at follow-up (Figure 4), in keeping with the value ascribed to VRS by learners. There were also no VRS-specific barriers that may have related to the hardware or software and the absence of in-session troubleshooting issues belies some of the concerns surrounding this modality [26].

Barriers to engagement with teaching opportunities

Limitations of our study include the number of learners, which were able to fully participate in our study, with many possible contributing factors to this. Our recruitment strategy involved invitation emails to all 212 FDs at our centre. This was supplemented by in-person invitations at the time of pilot, large-group VRS sessions at our centre, as well as at other mandatory teaching sessions. Despite 10 FDs initially expressing an interest in participating in this study, 5 of these did not respond to further and repeated attempts at contact. This dropout may be another symptom of the aforementioned challenges that trainees meet when engaging with postgraduate training more generally. Furthermore, at an academic and research-focused centre such as ours, the low response rate may also represent recruitment/survey fatigue or may simply represent a sense of futility in engaging with such quality-improvement initiatives.

The low number of participants means caution must be applied when drawing conclusions. However, whilst the sample size may appear limited from a numerical viewpoint, each interview was comprehensive and covered a range of themes, obtaining rich data that have resulted in deep, diverse and actionable insights that answer our research questions. The low number of participants allowed for a more in-depth exploration of individuals’ thoughts and a relative saturation of answers and themes during analysis suggested we captured key, shared opinions. By focusing on the quality of the data rather than the quantity, we have gained a comprehensive understanding of the impact of VRS and provide valuable and profound insights for guiding similar initiatives and ensuring their success. An additional consideration relating to the relatively low number of study participants, is the potentially diluted impact of troubleshooting issues and the amplified benefits of the debrief, both due to an inflated faculty-to-learner ratio. Finally, the faculty that conducted the interviews and delivered the teaching sessions were the same, potentially engendering bias in learner responses at the time of interview, despite a candid environment being actively fostered.

Our evaluation of current postgraduate medical education is the first to show a clear role for VRS in the teaching of the management of acute medical presentations, offers examples of learners incorporating learning points into their clinical practice and, more broadly, demonstrates the potential for transferable learning from the VRS sphere into real-life clinical practice. The overall positivity with VRS translated to a repeated desire from the learners to have safeguarded time to engage with this modality and, whilst providing such protected opportunities necessitates demanding investments in both resources and people, there remains an obligation on medical educators to facilitate these. Thoughtful integration of VRS could help improve learner clinical exposure whilst also allaying concerns about the content and structure of current postgraduate curriculums. More work is needed to evaluate VRS’ potential to enhance clinical competence as well as the feasibility of its implementation within postgraduate medical teaching programmes more widely.

None declared.

None declared.

None declared.

None declared.

None declared.

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

30.

31.

32.

33.

34.

35.

36.

37.

38.